Research Project: Political Science/Economics Analysis on Trade and Investment Rules in East Asia

Think About the RCEP: Research Agendas in Political Science and Economics

In November of 2020, 15 countries, including Japan, the ASEAN countries, China, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) that will constitute the world's largest free-trade area.

For the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE), a unique national research institute that has undertaken comprehensive research on economic development, it is extremely important to study both the social and economic effects of the RCEP and its future prospects. Thus, we have launched a research project to examine trade and investment rules in the East Asian region from the perspectives of political science and economics. This short article presents important research topics for future in-depth analysis that were identified in the kick-off meeting of the research project.

Table of Contents

Introduction: A Brief History of Trade Rule Formation and the Future

Topic 1: Market Access: A Supply-Chain-Efficiency Perspective

Topic 2: The Novelty of Rule Areas

Topic 3: The RCEP from the Perspectives of ASEAN and China

Conclusions: Implications for Japan and Future Research Topics

FUKAO Kyoji

President, IDE-JETRO / Professor, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University

Today, to kick off our research project, I would like to ask you to talk about what we can say about the RCEP with the information we currently have and what kind of research we should focus on in the future.

I think there are two difficult issues when conducting research on the RCEP. The first is that since various regional trade agreements (RTAs) are already in place in the Asia-Pacific region, our understanding of these existing RTAs needs to be as broad and up to date as possible to be able to examine the economic effects of the RCEP. For example, while the Peterson Institute for International Economics published a study on the economic effects of the RCEP last year, it is based on not recent data on existing RTAs. This is not very helpful, and a key issue therefore is to examine the impact of the RCEP using up-to-date data.

The second issue is that in order to achieve free and fair trade, it is not enough to reduce or eliminate tariffs; it is also important to use various international rules and harmonize countries’ rules and regulations. Since the RCEP includes countries like the ASEAN countries and China, whose regulations and institutions are not fully harmonized with international rules regarding subsidies, state-owned enterprises, investment regulations, and so forth, how international rules are formulated and applied is extremely important for the success of the RCEP. Moreover, since these challenges are closely intertwined with domestic issues, I think it is important to examine them from a broad perspective that includes, for example, political and social issues. The reason why we have invited specialists in politics, social issues, and ASEAN to participate in this project is that here at the IDE we recognize these issues and would like to fully investigate them.

I am looking forward to a productive kick-off meeting with many active discussions.

SATO Hitoshi

Director-General, Development Studies Center, IDE-JETRO

Further development of large RTAs, including the RCEP, may enable us to see a new form of trade rules, which can be shared across the world.

While trade liberalization in recent years has been driven by RTAs, such as the RCEP, the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements are the sole multilateral trade rule that governs world trade. As an introduction to today's discussion on RCEP, I briefly review the history of trade-rule formation.

The origin of the WTO can be found in the US Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934. Reflecting the fact that its trade policies had become too protectionist during the Great Depression, the United States promoted trade liberalization via the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. It featured reciprocal tariff reductions and nondiscrimination (most-favored-nation treatment), two core principles that were inherited by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the WTO1.

RTAs are discriminatory because trade liberalization only applies to participating countries. They are thus incompatible with the GATT/WTO principle of nondiscrimination. For this reason, the WTO rules allow RTAs as an exception to nondiscrimination but require them, for example, to achieve a higher level of trade liberalization on substantially all trade without raising trade barriers against external countries.

The number of RTAs has increased rapidly since the mid-1990s and there are currently more than 300 in force. What is the reason for this increase? Professor Baldwin et al., at the Graduate School of International and Development Studies in Switzerland, have pointed out that the trade diversion effect works in series2. RTAs tend to work to the economic disadvantage of countries that do not participate in them, making it a matter of joining or promoting other RTAs.

The economic rise of emerging economies is likely to generate a growing demand for a so-called 'level playing field,' centering on developed countries. The GATT/WTO has a history of granting various exceptions to developing countries, which makes it difficult to come up with new trade rules. Therefore, RTAs are a more practical platform for pursuing new trade rules.

Stimulated by regional economic integration throughout Europe and North America, ASEAN countries have been making efforts to achieve a free-trade area since the 1990s. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 also encouraged increased regional cooperation. In the early 2000s, multiple concepts of a large-scale free trade agreement (FTA) were proposed in East Asia, leading to the creation of the RCEP. ASEAN also entered into individual FTAs with neighboring countries including Japan, China, South Korea, India, and Australia. These FTAs helped to prepare the political and socioeconomic landscape for the RCEP.

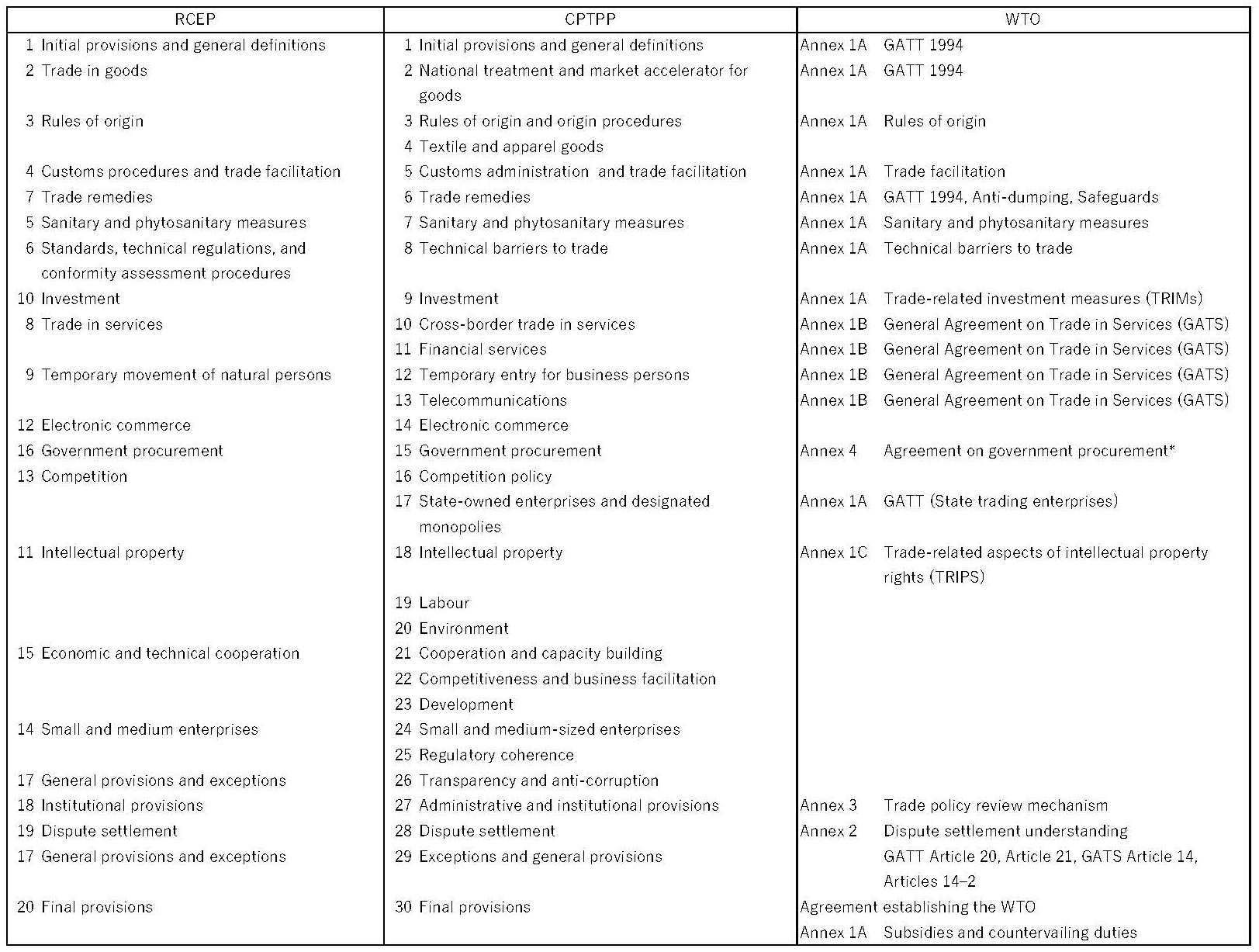

As the content of the RCEP will be discussed in detail later, it is omitted here. However, it is a comprehensive agreement that encompasses new fields not covered by the WTO, such as e-commerce (Table 1).

At the end of 2020, the EU and China signed an investment agreement, which was seen as 'preparing the ground' for an FTA. Now that they have left the EU, the UK has expressed a desire to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Although negotiations for an FTA between the US and the EU are ongoing, a new administration has only just taken over and it is difficult to predict what will happen next. Ideally, global trade rules should be pursued at the WTO, which is an institution that upholds the principle of nondiscrimination but is in a difficult situation to act as a forum for negotiating new trade rules. Further development of large RTAs, including the RCEP, may enable us to see a new form of trade rules, which can be shared across the world.

Table 1: An Overview of the RCEP, CPTPP, and WTO Agreements

*a plurilatera agreement

Notes

- Most-favored nation treatment means that concessions are applied to participating countries without discrimination.

- As a result of trade liberalization achieved through regional trade agreements, products from out-of-region countries, which would normally be cheaper to import, are replaced with imports from in-region countries. This is known as the trade-diversion effect; it can impair economic efficiency.

HAYAKAWA Kazunobu

Senior Research Fellow, Development Studies Center, IDE-JETRO

The effects of tariff reductions will be large on trade between Japan and China and between Japan and South Korea. Rules of origin also become more flexible1.

I will discuss the potential for trade expansion through the RCEP, focusing on tariffs and rules of origin. The RCEP is the first free-trade agreement (FTA) between Japan and China and between Japan and South Korea. Because firms can use RCEP-preferential tariffs, their trade is expected to greatly increase. In addition, even among countries that already have FTAs, RCEP-preferential tariff rates may be lower for some items in future years. This is especially true for products exported from Australia, New Zealand, and Japan to CLMV countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam).

Next, I would like to point out three effects of rules of origin. First, compared to those in existing FTAs in the region, rules of origin set in the RCEP are less restrictive for some items, which likely encourages more firms to take advantage of the RCEP's preferential tariffs.

Second, an approved exporter system will become available once the RCEP comes into force, and a system of self-certification by exporters will be introduced within a specified period of time after the agreement is implemented2. The firms that use these systems will be able to reduce the burden of certifying the origins of their goods.

Finally, the cumulation provision in the RCEP expands the area of originating inputs. For example, in a case where intermediate goods are imported from Japan, assembled in Thailand, and exported to China, it is difficult to satisfy the rules of origin in the ASEAN-China FTA for exports to China because the intermediate goods do not originate in Thailand. However, because the RCEP includes Japan, China, and Thailand in a single FTA, the rules of origin in RCEP will be easier to satisfy in such cases. Once the RCEP enters into force in all participating countries, the introduction of a full cumulation will also be considered. If introduced, this cumulation will make it even easier to meet the rules of origin.

KUMAGAI Satoru

Director, Economic Geography Studies Group, Development Studies Center, IDE-JETRO

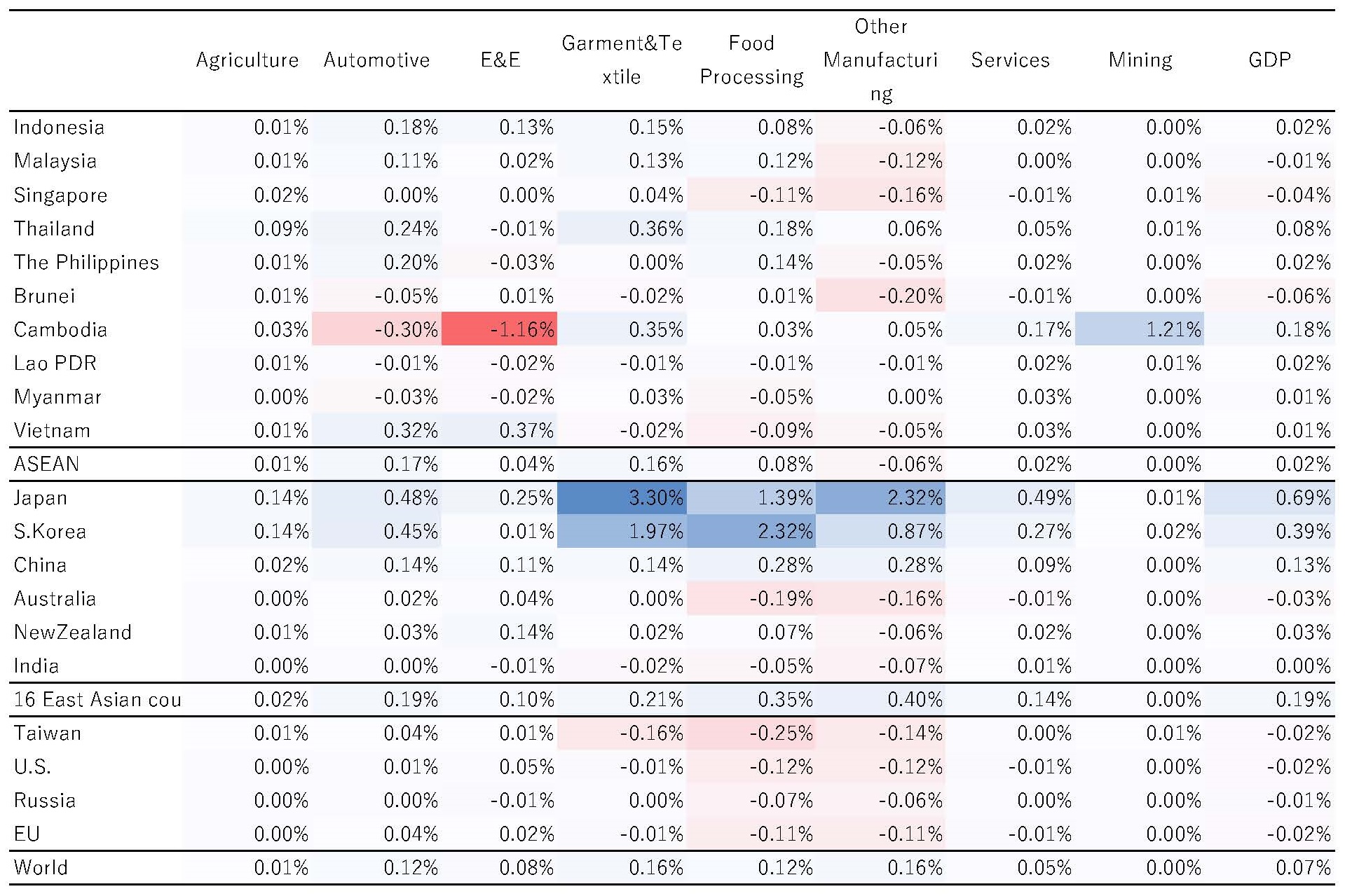

Provisional estimates of the impacts of tariff reductions by our simulation model indicate a great benefit for Japan3.

IDE-GSM (Geographical Simulation Model developed by IDE-JETRO) has estimated the provisional effects of tariff reductions, excluding such matters as the cumulative effects of rules of origin (Table 2). This is a rough estimate of the economic impacts of the RCEP by 2030, assuming that it comes into effect in 2021. As Dr. Hayakawa has pointed out, the trade-creation effect works strongly between countries that do not currently have an FTA. Japan and South Korea, in particular, appear to benefit significantly because they had no existing FTA with China before the RCEP. Overall, the economic impacts on Japan are significant. The effect of tariff reductions, alone, resulted in a 0.7% increase in Japan's GDP, which, in my experience of estimating other regional trade agreements, appears large. The effect was smaller in other countries, while some countries saw minor adverse effects.

One of the features of the IDE-GSM is the fact that the economic impact can be estimated at a sub-national level. For China, we estimate the impacts at one level below the provincial level; For Japan, we estimate the impacts at a prefectural level. Economic impacts can also be calculated industry by industry, which makes it possible to evaluate the economic impact on each sector in each region.

As a topic for future research, I would like to begin by considering and incorporating the cumulative effect of rules of origin. The next priority will be to study the impact of changing the membership of nations participating in the RCEP. For example, I would like to attempt a scenario that examines if India, which opted not to participate in the RCEP, decided to participate. Using to this method, it will be possible to estimate the value of RCEP membership in each country.

Conversely, how much would the overall benefit of the RCEP be reduced if Japan and China chose not to participate? I think it would be interesting to analyze the relationship between each country's contribution to overall RCEP benefits and the bargaining power of the individual member countries. 。

Table 2: The Tariff-Reduction Effects of the RCEP (as of 2030, Compared to Baseline)

Source: IDE-GSM calculations

(Discussion)

FUKAO: Could you explain a bit about how the cumulative effect of rules of origin is estimated in the IDE-GSM?

HAYAKAWA: The cumulation provision enables firms to comply more easily with the rules of origin. In our past simulation models, we took this effect into account by reducing non-tariff barriers. However, there might be a better way.

UMEZAKI: How will liberalization in areas other than tariffs, such as investment, be incorporated into the IDE-GSM?

HAYAKAWA: One simple way is to incorporate the effects of such non-tariff provisions as a reduction of non-tariff barriers. Also, it may be reasonable to take the effect of the investment chapter as that of increasing firms’ productivity.

ETO: How can such calculations reflect the expansion of connectivity?

KUMAGAI: We are incorporating the effects of physical-infrastructure development as reductions in logistic time and cost. Improvements to the institution, such as improvements to customs-clearance procedures, can be analyzed according to the reductions in the time required for their completion.

SATO: China’s 0.07% is a very low figure. Do you know the background behind this figure? India's impact is almost zero. What would have happened if it had joined the RCEP?

HAYAKAWA: China had already concluded on FTAs with all RCEP member countries excluding Japan. Furthermore, general tariffs in Japan have already been zero on nearly 50% of tariff-line items, so the new FTA, i.e., RCEP, does not produce large impacts on China’s exports to Japan. On the other hand, India has no FTAs with China, Australia, or New Zealand. So, if we include India as a member of the RCEP in our simulation analysis, its simulated economic impact could conceivably be greater than even that of Japan.

Notes

- Preferential tariffs under the RCEP apply to goods produced within the signatory countries. Rules of origin are rules that determine the origin of goods.

- The Approved Exporter System allows exporters who have been certified by the government or another organization to issue a certificate of origin.

- IDE-GSM is an applied general-equilibrium (CGE) model that has been under development at the Institute of Developing Economies since 2007. Based on spatial economics, we can carry out simulation analyses of changes in industries and population clusters that are associated with changes in transportation and transaction costs.

YANAI Akiko

Senior Research Fellow, Interdisciplinary Studies Center, IDE-JETRO

To study how advanced the RCEP is in the rule areas, its breadth and depth must be examined more closely. As for intellectual property, the RCEP strengthens this protection with its introduction of the TRIPS-Plus provisions.

Two aspects can be discussed when considering the RCEP’s rule areas: how advanced they are and how to effectively implement them. Today, I would like to focus on the former. Since all RCEP participating countries are members of the WTO, the WTO agreement can serve as a benchmark for understanding the RCEP's features. In addition, it is necessary to compare the RCEP with other many existing trade agreements in the region.

There are two axes to evaluate the progressiveness of RTAs: the breadth of the coverage and the depth of commitments. In terms of breadth, the RCEP deals with areas that are not covered by the WTO, including competition, e-commerce, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In that respect, the RCEP can be said to be ambitious. On the other hand, some areas covered by other agreements, such as the CPTPP, are excluded from the RCEP's scope including the environment, labor, and state-owned enterprises.

In terms of depth, taking intellectual property rights as an example, the RCEP has several TRIPS-Plus provisions that protect intellectual property rights beyond the level of the WTO agreement. The RCEP stipulates the authority to refuse or cancel trademark applications filed in bad faith. It also extends its protection to partial designs. These provisions go beyond what was included in the CPTPP.

On the other hand, the RCEP appears to be less advanced than the CPTPP in some respects. Regarding the WIPO-administered treaties, the CPTPP obliges member countries to join some of these treaties before it enters into force. The RCEP also requires its members to enter into seven listed multilateral agreements, however, it does not set a deadline for doing so. To be less rigid in obligation, the RCEP recommends members to “endeavour to ratify or accede” the Budapest Treaty, and it even provides support for the ratification of some treaties such as the Singapore Treaty and the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention1.

UMEZAKI So

Director, Economic Integration Studies Group, Development Studies Center, IDE-JETRO

Reservations are unavoidable if countries at different stages of development are to agree on advanced provisions. Ensuring the effectiveness of the agreement will be the focus going forward.

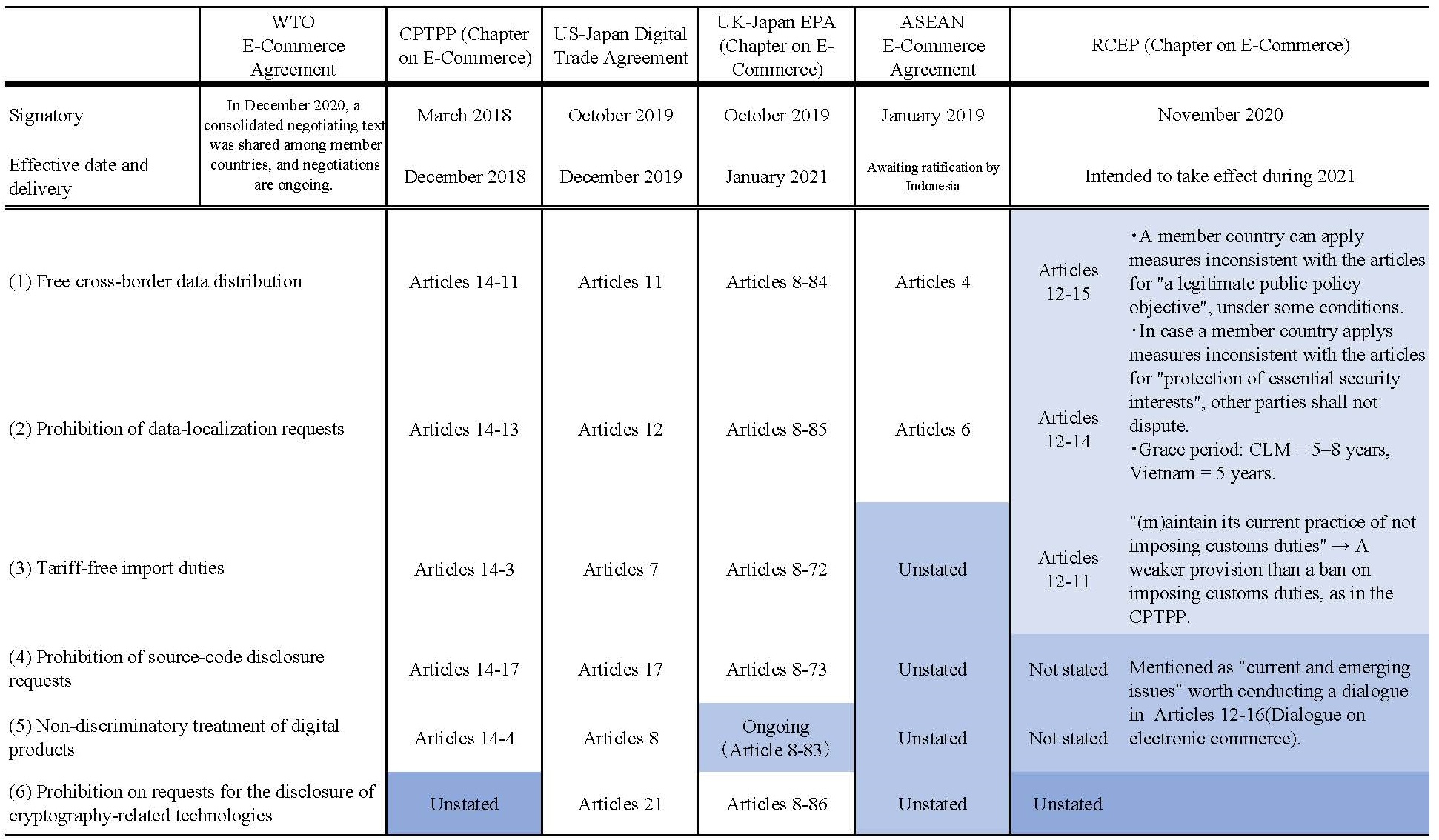

I would like to talk mainly about e-commerce and investment. Electronic commerce provisions generally concern the following: (1) free cross-border data flows; (2) the prohibition of data-localization requirements; (3) the non-imposition of customs duties; (4) the prohibition of source-code disclosure requirements; (5) the non-discriminatory treatment of digital products; and (6) the prohibition of cryptography-related technology-disclosure requirements (Table 3).

Of these, only the first three are clearly defined by the RCEP. Compared to the CPTPP, the RCEP gives the least-developed countries longer grace periods to implement some of the provisions. This leaves the restricting party with more room for discretion when it comes to exemptions on the grounds of public interest, including security. Both (4) and (5) are mentioned in the RCEP, but only as topics of future dialogue.

With respect to investment provisions, the scope of prohibitions of performance requirements in the RCEP is wider than that in the AJCEP, for example2. This may help improve the RCEP's legal stability and predictability. Although there are no major differences from the CPTPP, the RCEP grants the CLMV significant reservations in some areas, taking into account the nations' stages of development. Achievements in institutional aspects include the establishment of the RCEP Joint Committee and an RCEP Secretariat under the RCEP Ministerial Meetings (Chapter 18). It is hoped that the system will be designed in such a way that its functions and roles will enhance the efficacy of the agreement. However, in addition to the differences between the RCEP and CPTPP previously explained, differences regarding the interpretation and application of the electronic commerce chapter between party nations are not recourse to Chapter 19 (dispute resolution). Therefore, it will be necessary to closely monitor the efficacy of the RCEP's provisions and the actual process followed in practice, should such circumstances arise.

Table 3: Provisions on Electronic Commerce

Source: Created based on Itakura, Y. “DFFT (Data Free Flow With Trust) and Economic Security,” Research Report No. 6, Nakasone Peace Institute (in Japanese, December 24, 2020), Ministry of Foreign Affairs Homepage, and the provisions of the agreements.

(Discussion)

SUZUKI: Were e-commerce and intellectual property included in the RCEP, but not in existing ASEAN+1 FTAs? Would it be correct to assume that the impact of these areas on each party of the RCEP would depend on whether or not there is an existing FTA?

YANAI: Intellectual property is slightly different from other areas in RTAs because the TRIPS agreement has an MFN provision in itself. If an RTA provides more favorable intellectual property contents than the TRIPS agreement, such provisions are applied uniformly, not only to the RTA members but also to all WTO members. Compared to ASEAN+1 FTAs, I believe that intellectual property protections are strengthened in the RCEP.

UMEZAKI: Because e-commerce is a new field, many aspects are not included in FTAs between developing countries. Since developing countries are participating in the RCEP, several reservations and non-conforming measures remain. However, I see the establishment of a framework of rules, itself, as a major step forward.

HAYAKAWA: China has recently formulated legislation related to cyber data. Won't the RCEP come into conflict with these domestic laws? Won't this be a problem at the ratification stage? Of course, exceptions may be made for reasons such as security.

UMEZAKI: The reason for including various reserved conditions in the e-commerce provisions is precisely to ensure consistency with each country's domestic laws.

ETO: I think that's a real concern. China's basic attitude is that domestic law takes precedence. For example, the Coast Guard Law, which comes into effect in February of this year, may misalign with international law in practice. On the economic side, China seems to think that it can win even if it follows market mechanisms under international rules. It will claim that it is playing by the rules. One major issue likely to arise involves international standards. Over the past two years, China has been formulating “China Standards 2035," the successor economic strategy to "Made in China 2025,” in an attempt to unify domestic standards and make them internationally-approved.

Notes

- The Budapest Treaty: the Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure (entered into force in 1980); The Singapore Treaty: the Singapore Treaty on the Law of Trademarks (entered into force in 2009); The 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention: the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (entered into force in 1968 and thirdly revised in 1991).

- AJCEP, the Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Partnership among Japan and Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is an FTA between Japan and ASEAN.

SUZUKI Sanae

Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo

Does the RCEP remain an ASEAN-led FTA in future rule-making and implementation?

I would like to talk about the RCEP for ASEAN from three perspectives:

First, on the institutional side, the RCEP was proposed and initiated by ASEAN. Japan and China each proposed an East Asian FTA with different membership. Since their proposals were difficult to be materialized, ASEAN eventually proposed the RCEP by making membership open to various countries; this resulted in 16 countries participating in negotiations. The ASEAN countries located the RCEP in an ASEAN-led framework linking with ASEAN's economic integration and the ASEAN+1 FTAs. In other words, the RCEP concerns discussions about the centrality of ASEAN, which enables ASEAN to be in the driver's seat. I would like to closely examine to what extent implementation of the RCEP will be institutionally linked to ASEAN, including whether the RCEP Secretariat will be established within the ASEAN Secretariat.

The second perspective concerns how ASEAN member states perceive the economic impacts that the RCEP would have. In Thailand, it is reported that people expect exports of agricultural products to increase. However, in Indonesia, there are concerns that the RCEP will increase competition, which will negatively impact some industries. Although it is ultimately a matter of perception, it may lead to political moves.

Lastly, regarding political-security, the East Asia Summit (EAS) and ASEAN+3, where discussion of an FTA in East Asia had taken place, are no longer functioning as the framework for the RCEP because the RCEP was not proposed as a project conducted in these frameworks and the United States and Russia later participated in the EAS. However, it is important to closely observe how the RCEP becomes positioned in the future, given the ongoing emergence of new regional concepts such as the Indo-Pacific.

ETO Naoko

Research Fellow, Area Studies Center, IDE-JETRO

China has attached great importance to multilateral trade as part of its international strategy and it will make strong use of the RCEP in both economic and political aspects.

I would like to highlight the following two topics: China views the RCEP in a very positive way, and the RCEP must be evaluated comprehensively, not merely from an economic perspective.

As for economic benefits, China very much appreciates the fact that it now has the largest free-trade zone in the world. The government's view also highlights the finding that, in 2019, China invested $16 billion in 14 participating countries and participating countries invested $14 billion in China. Then there are China's acknowledgments that the initiative behind the RCEP lies with ASEAN and that the RCEP is a collective upgrade of the ASEAN+1 FTAs. China has not claimed to have led the RCEP negotiations.

However, the political gain must be very important to China. Currently, I think that China's strategy is to avoid dealing with the United States head-on. Instead, if China sits at the center of global governance while the United States suffers, then even the latter will be willing to listen to some of what China has to say. At the United Nations General Assembly last September, President Xi Jinping announced a goal of carbon-neutrality by 2060. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, President Xi has cited China's global contributions, including the country's supply of masks and vaccines. In the economic field, he has stated that China will promote cooperation with Asia (RCEP) and Europe (the EU-China investment pact) as well as promote multilateral trade.

As seen in the discussion of international standards I spoke about earlier, China's goal is to increase its real economic influence. The greater its economic dominance, the more discourse power it will have to guide the international community. In other words, China is making various ambitious moves because it believes that it could possibly convert economic power into political power.

(Discussion)

SUZUKI: The local newspapers of ASEAN countries have reported that the Trump administration in the United States turned its back on international rules, while China sought to promote its stance of respecting international rules by agreeing to the RCEP. With the Biden administration now in power, to what extent is the discussion of China's emphasis on international rules in US-relations still valid?

ETO: I think they would normally act in accordance with international rules. However, the problem is that when such rules conflict with China's national interests, or what can be called China's core interests, China reverts to domestic logic. I think there is also the traditional Chinese idea that you should follow what the powerful say. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has taken the position, not only domestically but also in relation to the international community, that "it is powerful and says the right things, and therefore people should follow it.” The problem is that this code of conduct understands and uses the rules, but does not follow them when they do not fit the party's understanding, which I think is basically a matter of norms. From the point of view of foreign countries negotiating the rules, it becomes a question of credibility, whether those rules will ultimately be followed or not. I think that a realistic solution would be to present a counter-argument about how to conduct economic activities in a state without trust.

YANAI: What you said about rules and norms makes sense. In the field of intellectual property rights, this Chinese perspective regarding “rules” affects measures against counterfeit and pirated goods. If the harmonization of rules does not ensure the control of counterfeit and pirated goods, we will have no choice but to strengthen border measures, such as those introduced by the RCEP. It is difficult to say whether the creation of such antagonistic and restrictive rules would be moving in the right direction.

Also, I would like to ask Dr. Suzuki, how ASEAN members would overcome the contradiction between the double faces: the diverse ASEAN member countries having conflicts of opinion arising from economic disparities within the region, and the monolithic ASEAN negotiating together on trade agreements against extra-regional countries, in relation to the RCEP?

ETO: That is a very difficult task. If we do not take a firm stance and incorporate coercive or (depending on circumstances) punitive measures, in the long run, the rules will either collapse or China will create rules that it can follow.

SUZUKI: The elimination of intra-regional disparities is important, but there is a stronger awareness that eliminating disparities requires the economic development of ASEAN as a whole. The "ASEAN minus X" formula was introduced to enable prepared countries to implement economic agreements first, followed by other countries when they became ready. Since the 2000s, it moved to the "2 + X system," in which liberalization rules, as ASEAN agreements, could be pursued by at least two countries (e.g., Singapore and Malaysia). There appears to be a recognition that it would be effective to put peer pressure on the CLMV, encouraging economic growth by attracting further investment into the region.

SATO: Even if rules are established, there will be disputes when it comes to their implementation. The question of how to ensure the implementation of the RCEP is really important. There is also the question of how to deal with a country that lacks credibility. You cannot build a deep, cooperative relationship with a country with that kind of mindset. Many countries are participating in the RCEP. I think it would be good to create an environment in which uncooperative responses that don't follow RCEP rules bounce back on the responder and cause losses.

FUKAO Kyoji

Based on today’s discussions, we have found that there is much more research to be done on the harmonization of rules among RCEP member countries. How to enhance balanced development within the East Asian region is another important topic.

There is a famous book by E. H. Carr called The Twenty Years’ Crisis: 1919-1939, which looks back at the interwar period. At the beginning of the book, there is a lot of criticism of the principle of free trade, which used to annoy me, but today’s discussion has made me keenly aware that we are now in a similar situation to the one Carr described. Achieving peaceful and balanced economic development in East Asia will be a very difficult task, and we need to be realists who fully understand such difficulties.

In this respect, too, the issue of rules is crucial, as well as how to gauge their effectiveness. And based on this, establishing a secretariat and monitoring the implementation of the agreement are key. There needs to be a mechanism to ensure that the points that need to be protected are protected.

While China is a major power, its population is aging and its growth will most likely decline. The confrontation between the United States and China will not be easily resolved, and pressure on China will continue. India and ASEAN also have large populations and if there is a “Great Convergence,” as Professor Richard Baldwin calls it, in which GDP per capita gradually converges, this may reduce China’s relative importance. I, therefore, think that it is crucial to enhance balanced growth within East Asia through the RCEP.

An extremely important issue that unfortunately is not included in the RCEP is that of subsidies, including state-owned enterprises. I am working on a separate research project at the IDE to quantitatively examine this issue and hope to use the findings to contribute to discussions in future seminars.

Other extremely important issues, I think, include how the RCEP changes political dynamics within the ASEAN countries compared to the ASEAN+1 setup, as well as inequality within these countries. Thus, there is a lot of research to be done. I know that research on rules is particularly difficult and I thank you for your efforts.

Thank you very much.