レポート・報告書

アジ研ポリシー・ブリーフ

No.154 Driving factors of ASEAN commitment to RCEP negotiation

Sanae Suzuki

PDF (312KB)

- The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) helped Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states maintain their commitment to Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) negotiations, and also provided them with the incentive to launch the RCEP as a free trade agreement that is qualitatively different from both the TPP and the CPTPP.

- ASEAN regards conclusion of the RCEP as an opportunity to promote the Southeast Asian market and to strengthen ASEAN’s position as a rule-maker.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was completed in 2020, is a free trade agreement (FTA) proposed by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Since ASEAN already has FTAs with RCEP signatory countries, the trade effects of the RCEP on ASEAN members are not as great as those on non-ASEAN members (Kumagai and Hayakawa, 2021). Then, why did ASEAN member states commit to long-term RCEP negotiations? This article explores the factors behind their choice using data from local newspapers and provides a future outlook.

ASEAN and FTAs

ASEAN member states agreed to form the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) in 1992, and tariffs have been abolished within the ASEAN region. After the formation of the AFTA, further steps were taken to eliminate non-tariff barriers such as customs clearance procedures. ASEAN has promoted its economic integration through the ASEAN Economic Community.

ASEAN also completed FTAs with countries with which it had established close relationships (referred to as “dialogue partners”). Since the 2000s, FTAs have been completed with China, the Republic of Korea, Japan, Australia/New Zealand, and India. These are known as “ASEAN-plus-one” FTAs. ASEAN also agreed that each of its member states would sign an FTA with the European Union (EU). As of 2019, the FTA between Singapore and the EU has come into effect, and Vietnam has also signed an FTA with the EU.

Several studies have investigated the political factors behind the formation of FTAs. It has been argued that countries that maintain close and amicable relationship with each other, such as allies, are more likely to form FTAs (Yukawa, 2020). It has also been suggested that the AFTA is the result of the pursuit of political cooperation and the building trust among ASEAN member states (Kim et al., 2016: 332). ASEAN-plus-one FTAs are FTAs with dialogue partners, a fact that supports the argument that close relations is an important condition for the formation of FTAs. This is also the case for the RCEP, which is also an FTA between ASEAN member states and its dialogue partners. However, this perspective focuses on the conditions for the formation of an FTA and does not fully explain the motivations for its formation.

RCEP and policy diffusion

“Diffusion” is often pointed out as a motivation for the formation of FTAs. According to this view, signing an FTA is considered out of concern that failure to do so would reduce competitiveness (Risse, 2016). In other words, an FTA is imitated as a policy model. The formation of ASEAN-plus-one FTAs is said to be the result of dialogue partners being influenced by diffusion and seeking FTAs with ASEAN (Oyane, 2016).

It has been pointed out that ASEAN proposed the RCEP because it was afraid that the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) and discussion on the China-Japan-Korea FTA would threaten its competitiveness (Sukegawa, 2019). This highlights the impact of diffusion.

Does diffusion continue to have an impact even after the RCEP proposal? To answer this question, this article explores how the RCEP was featured in the local newspapers of five ASEAN member states: the Bangkok Post (Thailand), Jakarta Post (Indonesia), New Straits Times (Malaysia), Straits Times (Singapore), and Philippine Daily Inquirer (Philippines).

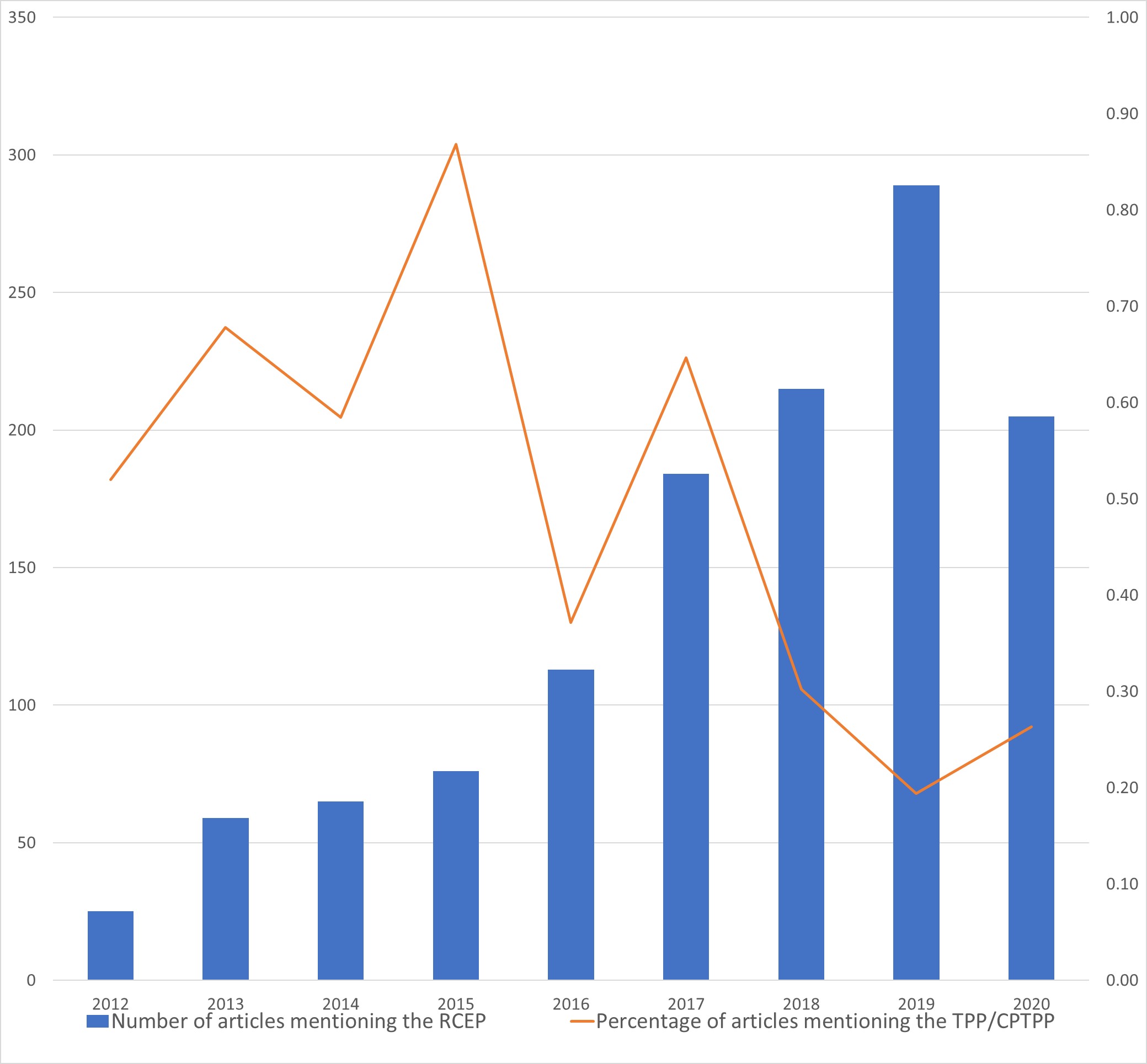

In these local newspapers, the RCEP was frequently mentioned in connection with the TPP and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership the (CPTPP). Figure 1 shows the number of articles mentioning the RCEP (left axis) and the percentage of articles including the TPP/CPTPP (right axis) in those articles from 2013, when the RCEP negotiations began, to 2020, when it was concluded.

Figure 1: Relationship between RCEP and TPP/CPTPP

in the local newspapers of five ASEAN countries

(Source: the author)

First, the TPP/CPTPP was often mentioned throughout the RCEP negotiation period. This suggests that the impact of diffusion continued even after the RCEP proposal. In particular, in the first half of the RCEP negotiations, the TPP/CPTPP was mentioned more frequently, and the negotiation of the TPP/CPTTP may have helped ASEAN member states maintain the momentum of the RCEP negotiations. However, this relationship was weakened after the United States withdrew from the TPP in early 2017. This may indicate that the interest of ASEAN member states in the TPP was tightly linked with their eagerness to access the U.S. market.

Within ASEAN, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam are TPP/CPTPP signatories, and Thailand and Indonesia, non-signatory countries, have explored the possibility of joining (Jakarta Post, April 17, 2013; Bangkok Post, 21 October 2015). Some countries have hesitated to join because of the need to protect their domestic industries. However, they also fear trade diversion effects that would favor Vietnam, a signatory country. (Bangkok Post, November 23, 2015; Jakarta Post, January 26, 2016). As the United States withdrawal from the TPP became more certain, these countries became less interested in the TPP as well as less concerned with its trade diversion effects, and more eager to conclude the RCEP (Bangkok Post, November 16, 2016).

Differences between RCEP and TPP

Although interest in the TPP/CPTPP declined after 2017, the TPP/CPTPP remained a reference point in RCEP negotiations when ASEAN member states discussed the type of FTA they expect the RCEP to be during the negotiations.

Iman Pambagyo, who chaired the RCEP negotiations, said that ASEAN must have one voice when negotiating with non-ASEAN members (Jakarta Post, March 27, 2018). His remark indicates that there may have been disagreements within ASEAN regarding the level of liberalization and the areas to be targeted during the negotiations. Such disagreement can be assumed given the fact that there are TPP/CPTPP signatories and non-signatories within ASEAN.

However, disagreements between ASEAN and non-ASEAN members were more significant than those within ASEAN. For example, ASEAN, along with India, objected to other members pushing for intellectual property rights clauses beyond international trade rules in the RCEP (Jakarta Post, December 2, 2016). As for the services sector, non-ASEAN members pledged access to 100 or more sectors, whereas ASEAN member states were willing to open fewer sectors (Jakarta Post, September 1, 2018). In response to the view that Japan and Australia wanted liberalization comparable to the TPP (Jakarta Post, May 31, 2018), Pambagyo warned them not to “TPP-nize” the negotiation (Jakarta Post, June 12, 2017).

Sending political signals

After the United States withdrew from the TPP, there was a move to promote the RCEP as a political instrument to accelerate free and open economic activity, particularly in Indonesia and Singapore. For example, it was suggested that the RCEP could provide a model for FTAs integrating the least developed and developed economies (Jakarta Post, February 20, 2017), and that the completion of the RCEP could serve as evidence that the Southeast Asian region was economically resilient and open to businesses. (Straits Times, April 29, 2017; June 30, 2018; 2 September 2019).

ASEAN wanted India to stay in the RCEP. After India’s announcement of its withdrawal at the end of 2019, Vietnam, the ASEAN chair country at that time, presented a package in May 2020 to encourage India’s participation (Bangkok Post, 19 May 2020). India ultimately chose to withdraw. India’s participation would have increased its economic attractiveness. In addition to such economic interest, ASEAN was eager to secure India’s participation even if it meant that some compromises had to be made to accommodate India’s interests and wishes. This stance may reflect ASEAN’s intention to strengthen its position as a rule-maker, using the RCEP as a model for FTAs.

With the completion of the RCEP, the next agenda items include the establishment of the RCEP secretariat and its functions, and the consideration of expanding membership. Regardless of whether they are TPP/CPTPP signatories, it is a common interest for ASEAN member states to maintain the attractiveness of the RCEP whose signatories include neighboring countries. Since the beginning of the negotiations, ASEAN’s interests have been strongly reflected in the RCEP. Such path dependence could be used to seek close relations with ASEAN as a condition for new membership, and to promote the implementation of economic and technical cooperation along with ASEAN’s interests and practices. However, as seen in the RCEP negotiations, there are many cases in which the interests of countries outside the region differ from those of ASEAN. ASEAN will be tested on whether it can continue to strengthen its position as a rule-maker.

(Sanae Suzuki / The University of Tokyo)

<References>

- Oyane, Satoshi (2016), “FTA/TPP no seijigaku” (The Politics of FTAs and the TPP) in Satoshi Oyane and Yutaka Onishi (eds.), FTA/TPP no seijigaku: boeki jiyuka to anzen hosho/shakai hosho (The Politics of FTAs and the TPP: Securitization of Trade Policy?), Yuhikaku.

- Kumagai, Satoru and Kazunobu Hayakawa (2021), “Economic Impacts of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership: Analysis Using IDE-GSM” IDE Policy Brief, No. 147.

(https://www.ide.go.jp/Japanese/Publish/Reports/AjikenPolicyBrief/147.html, last viewed on November 10, 2021) - Sukegawa, Seiya (2019) “RCEP to nihon no higashiajia seisan nettowaku” (RCEP and Japan’s East Asia Production Network), in Koichi Ishikawa, Keiichi Umada, and Kazushi Shimizu (eds.), Ajia no keizai togo to hogo shugi: kawaru tsusho chitsujo no kozu (Economic Integration and Protectionism in Asia: The Changing Composition of the Trade Order), Bunshin-do.

- Yukawa, Taku (2020) “Higashiajia keizai togo to anzen hosho no renkan: kokusai seijigaku no shiten” (The Linkage between East Asian Economic Integration and Security: A Perspective from International Politics), in Fukunari Kimura (ed.), Korekara no higashiajia: hogo shugi no taito to mega FTA (East Asia in the Future: The Rise of Protectionism and Mega-FTAs), Bunshin-do.

- Kim Soo Yeon, Edward D. Mansfield and Helen V. Milner (2016) “Regional Trade Governance,” in Tanja A. Börzel and Thomas Risse (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.323-350.

- Risse, Thomas (2016) “The Diffusion of Regionalism,” in Tanja A. Börzel and Thomas Risse (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.87-108.

* The author gratefully acknowledges Hitoshi Sato, of the Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization, for valuable comments provided on the draft of this article.

本報告の内容や意見は執筆者個人に属し、日本貿易振興機構あるいはアジア経済研究所の公式見解を示すものではありません。