IDE Research Columns

Column

US–China Economic Conflicts: East Asian Responses to the Restructuring of the International Division of Labor

Ke DING

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

October 2024

The international division of labor involving East Asia has been forced to significantly change as a result of conflicts between the US and China. With regard to production, global value chains centered on China have been rapidly restructured. As for research and development, technological decoupling is underway, and the previously open innovation system is becoming semi-closed. Furthermore, skepticism is growing about the feasibility of an international division of labor among countries with disparate economic systems. Based on the research findings in our book on this topic, this column analyzes the impacts of US–China economic conflicts on East Asian economies and explains the responses of relevant countries and regions.

The economic conflicts between the US and China have gained considerable attention across various dimensions, including a growing trade war, frictions in the high-tech sector, and inter-system competition. In our recent book, US-China Economic Conflict: East Asian Responses to the Restructuring of International Division of Labor, my colleagues and I analyze each aspect of the US–China economic conflict to provide a more holistic understanding of this important, ongoing issue.

Trade War: Restructuring East Asian Production Networks

As a result of interactions involving comparative advantages, consumer markets, and linkage costs, the international division of production labor in East Asia has been significantly restructured since the 2010s.1 This is a more complex story than a common trade war-restructuring scenario.

First, China’s comparative advantage has changed as wages in the country have risen since the early 2010s. In addition, labor disputes, electricity shortages, and stricter environmental regulations have become more significant, increasing risks stemming from a concentration of production in China. In search of lower wages, many companies in labor-intensive industries such as textiles and footwear were seeking to relocate from China to neighboring countries even before the US–China trade war began in 2018.

Second, the US provides a huge consumer market that supports East Asia’s export-oriented industrialization. However, since the 2010s the rise of the Chinese market significantly expanded China’s presence in the East Asian Production Network. In 2020, China became the largest export destination for all East Asian countries and regions except Vietnam.

Third, the trade war that began in 2018 significantly increased direct linkage costs between the US and China markets. Many East Asian countries and regions have benefited from the trade war. For example, the Vietnamese economy has grown significantly, both in foreign direct investment and exports to the US since the outbreak of the trade war. However, the main factor in transferring production to Vietnam has been foreign capital, and thus the benefits to the Vietnamese economy in terms of export value-added and the development of local suppliers have been limited.

Under the interactions of the three variables identified above, the international division of production labor with respect to China may be split into two in the future. The first would be a self-contained production and distribution system centered on the Chinese market. The other would be established to avoid the concentration of production in China. In this case, firms engaged in export-oriented production located in China would continue to reorient their production bases to other parts of the world, especially East Asia.

However, it will be difficult to completely eliminate China’s influence on global supply chains for the time being. There is a difference between industries in which the US has an overwhelming influence in terms of both technology and markets, such as electronics, and those in which it does not. The increasing advantage of intermediate goods manufacturing in China should also be considered. Many developing countries face the dilemma that as their exports to the US grow, imports of intermediate goods from China will continue to increase.

High-Tech Friction and East Asian Responses

The US government, which believes China’s technological advances in the high-tech sector will undermine peace and prosperity in the US, has promoted technological decoupling from China. It has blocked China’s access to advanced technologies and reduced the high-tech supply chain’ dependence on China. These measures have affected the East Asian high-tech industry in the following four ways.

First, US export and investment controls have had a direct impact on China’s high-tech industry. For example, excluding Huawei from the 5G telecommunications networks of developed countries and restricting its semiconductor imports caused a significant 28.9% drop in Huawei’s sales in 2021, placing the company in a difficult situation.

Second, semiconductor export restrictions targeting Chinese companies triggered a global semiconductor supply shortage starting in East Asia after 2020. Japan, the US, and Germany, keenly aware of the need to ensure the safety of the semiconductor supply chain, started attracting investments from the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation.

Third, technology decoupling measures implemented by the US triggered countermeasures by China, which led other major countries to re-establish high-tech export controls and investment screening systems.

Fourth, in response to frictions in the high-tech sector, both the US and China took steps to re-build their R&D capabilities. The US began to consider rebuilding an innovation network centered on its allies. China has also formed various innovation consortiums consisting of domestic players to develop cutting-edge technologies such as 5G, artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and biotechnology.

However, it is possible to avoid a phase of widespread conflict with a marked reduction in the exchange of knowledge and personnel in the global sphere. At the firm level, as the major driving force of globalization, multinationals are not forced to choose between the US and China. Moreover, modern innovation activities can only be deployed efficiently when they are closely linked to the production sites where users of new technologies are located (Berger 2013). It would not be surprising if a paradoxical phenomenon occurs in the future, in which the more the US and its allies increase their innovation activities, the closer their ties with China become in terms of manufacturing and markets. Finally, it is also important to note the US and China are more deeply aware than any other countries that there are no winners when innovation atrophies due to the lack of exchange of knowledge and human resources. Stopping the China Initiative in the US and implementing the dual-cycle strategy by China symbolically illustrate this point.

Inter-system Competition and Institutional Convergence

If the US–China conflict becomes protracted, the mechanism of institutional convergence, namely a gradual increase in similarities across economic systems, would become more notable among the parties involved in inter-system competition.

This mechanism was elucidated by Jan Tinbergen, the first Nobel laureate in economics, in the 1960s as convergence theory. According to Tinbergen (1961), both communist and capitalist systems, under the pressure of intense inter-system competition, adopt each other’s strengths to compensate for the weaknesses of their own system. As a result of this mechanism, elements of market-based economies penetrated the communist bloc, whereas in free economies, the public sector expanded; thus, the two systems gradually tend to converge. Cui (2019) cites Tinbergen’s theory of convergence in pointing out the possibility of institutional convergence between the US and China.

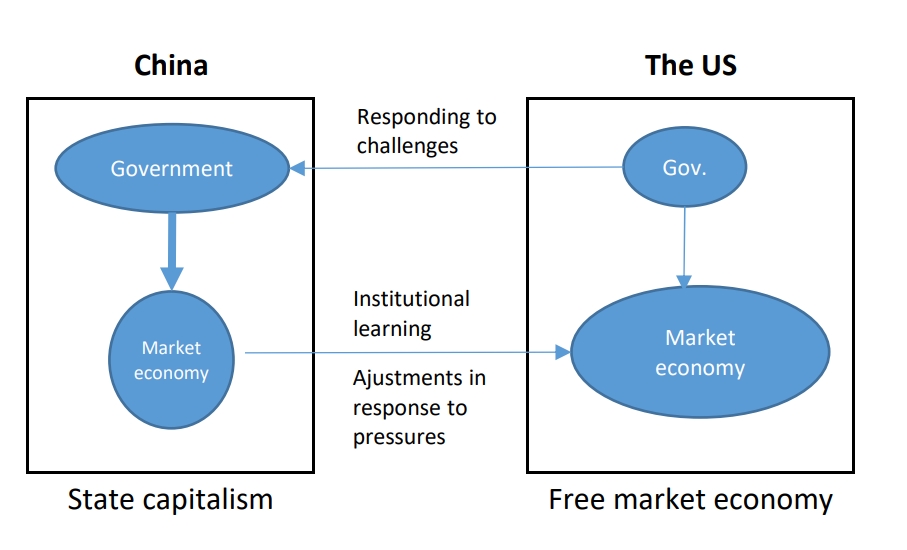

While Tinbergen and Cui’s insights are indeed illuminating, it is important to note the clear differences in the convergence mechanisms between the US and the former Soviet Union, and between the US and China. First, the economic systems adopted by the US and the Soviet Union were fundamentally different. In contrast, China’s system, referred to as “state capitalism” (the official name in China is a “socialist market economy”), emphasizes the role of the state but also naturally has a capitalist, or market-driven aspect. As a latecomer, China has been learning from the institutions and experiences of advanced market economies, especially the US. Conversely, the US originally had no incentive to learn about China’s economic system, but in response to the challenge China represents the US has been forced to strengthen government intervention on the economic front.

Figure 1. Mechanism of Institutional Convergence in the US and China

Note: The thickness of the vertical arrows denotes the extent to which governments can intervene in their respective economies and oval sizes indicate the relative influence of the government and market players in the countries’ economic systems.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Another important point that differentiates institutional convergence between the US and the former Soviet Union is that due to the deep interdependence between the US and China, the latter wishes to maintain the existing international division of labor with respect to the US. For this reason, China often makes certain concessions and institutional adjustments in response to US pressure.

It is widely recognized that the international division of labor will be promoted among countries with common institutional frameworks in the future. However, because of the mechanism of institutional convergence, the institutional foundation needed to maintain the division of labor between the US and China will remain intact, at least to some extent.

Conclusion

As discussed above, due to US–China economic conflicts, direct economic ties between the two countries will unavoidably weaken, and some production and innovation resources will be transferred from China to other parts of East Asia, benefiting latecomer countries and regions. However, given China’s strong production capacity, huge domestic market, and the mechanism of institutional convergence, it is unrealistic to completely remove the Chinese factor from the global system of production and innovation.

Author’s Note:

This column is an abbreviated version of Ding, Ke. 2023. “Introduction Chapter: Three Dimensions of US-China Economic Conflict.” In US-China Economic Conflict: East Asian Responses to the Restructuring of International Division of Labor, edited by Ke Ding, 1-33. Tokyo: IDE-JETRO (In Japanese).

Note:

- Inomata (2019) uses these three variables to explain the formation mechanism of the East Asian Production Network in 2000s. Following this framework, we analyze the changes of East Asian Production Network after 2010 in our book.

References

Berger, Suzanne. 2013. Making in America: From Innovation to Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cui, Zhiyuan. 2019. “Decoupling or Convergence?” China Daily, October 8, 2019. (https://www.lishiyushehui.cn/article/download/944, accessed on 30 August 2024).

Inomata, Satoshi. 2019.Global Value Chain.Tokyo: Nikkei Publishing (In Japanese).

Tinbergen, Jan. 1961. “Do Communist and Free Economies Show a Convergence Pattern?” Soviet Studies 12(4): 333-341.

Author’s Profile

Ke Ding received his PhD degree in economics from Nagoya University. He has been working at IDE-JETRO for nearly 20 years. His research field includes industrial organization, global value chain, innovation and Chinese economy.

Other Articles by This Author

Ding, Ke. 2012. Market Platforms, Industrial Clusters and Small Business Dynamics: Specialized Markets in China. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Ding, Ke, Toshitaka Gokan, and Xiwei Zhu. 2017. “Small Business and the Self-Organization of a Marketplace.” Annals of Regional Science 58 (1): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-016-0800-7

Humphrey, John, Ke Ding, Mai Fujita, et al. 2018. “Platforms, Innovation and Capability Development in the Chinese Domestic Market.” European Journal of Development Research 30(3): 408-423. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-018-0145-4

Ding, Ke, and Shiro Hioki. 2024. “Intellectual Property Strategy and the Governance of Technological Platform-Driven Global Value Chains: The Case of Qualcomm.” Competition & Change 28(1): 165-188. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294231190168

* Thumbnail image: Chip war between USA and China (Wong Yu Liang/ Moment/ Getty Images).

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.