IDE Research Columns

Column

Calculating the Impact of Global Decoupling on the Global Economy

Satoru KUMAGAI

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

April 2023

In this study, we estimate the impact of decoupling on the global economy with the Institute of Developing Economies-Geographical Simulation Model (IDE-GSM), a computable general equilibrium model that was developed for both sectoral and within-country regional analysis. Depending on the extent of decoupling, the global economy would suffer from substantial income decreases. Moreover, there would be significant negative impacts on the gross domestic product for the Eastern (including China and Russia) and Western (including the United States) camps, while neutral countries, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries and those in South America, would profit from the others’ disputes. The implication of the findings is that the more profound the conflict between the two camps, the greater the advantages of being neutral.

Computable General Equilibrium Model Analysis of Global Decoupling

Since the United States (U.S.).-China trade war that began in 2018, concern over global economic decoupling has significantly increased. Meanwhile, Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine has further exacerbated the fears of global decoupling. In Kumagai et al. (2023a), we estimated the impacts of the economic sanctions on Russia and Belarus by the “unfriendly” countries of Russia, including the U.S. and European Union (EU) countries. Although the impact on the global economy would be negligible at 0.0%, the gross domestic product (GDP) of Russia and Belarus would suffer a loss of −0.6% and −2.2%, respectively, according to the baseline scenario in 2030. This is because (despite its substantial military presence) Russia’s economy is relatively small in terms of GDP and comparable to that of South Korea or Brazil.

If further global decoupling were to occur, then it could be divided into three camps: the U.S. camp (Western), the Chinese-Russian camp (Eastern), and neutral countries that do not join either camp. Thus, we created two additional scenarios1 to examine how this decoupling would affect Japan, Asia, and the global economy, as well as the impact on each country and region. The impact on each country and region was estimated by using the Institute of Developing Economies-Geographical Simulation Model (IDE-GSM),2 a computable general equilibrium model that was developed for both sectoral and within-country regional analysis.

Assumptions on the Division of the World

This analysis assumes that the world is divided into the U.S. camp (Western) and the Chinese-Russian camp (Eastern). The countries in each camp are as follows. Note that there are neutral countries that do not join either camp.

Western camp: A total of 34 countries and regions with foreign policy similarities to those of the U.S., including the U.S., the United Kingdom, 27 EU countries, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Australia.3

Eastern camp: A total of 16 countries covered by the IDE-GSM that are subject to some form of economic sanction by the U.S. (as of January 2023), namely, China (including Hong Kong and Macau), Russia, Belarus, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Iran, Iraq, Yemen, Lebanon, Myanmar, Libya, Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, and Somalia.

Scenarios

Simulations of the impacts of global decoupling were performed according to the following scenarios.

The baseline scenario assumes no decoupling (no further increase in trade barriers from both camps), while considering changes in the tariff rates between the two countries due to the U.S.-China trade war that began in 2018 and the sanctions against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.4

In Scenario 1, additional non-tariff barriers (NTBs) are imposed on trade between the East and West after 2025, which are equivalent to the tariff rate increases on the U.S. side during 2018–2019 due to the trade war between the U.S. and China.5

In Scenario 2, the “worst case” scenario, additional NTBs equivalent to 100% tariffs are imposed on trade between the two camps.

Here, we estimate that the decoupling between the Eastern and Western camps will continue after 2025 until 2030, and the impact of the division is examined by calculating (for each country, region, and industry) the deviations from the GDP in 2030 under the baseline scenario without decoupling.

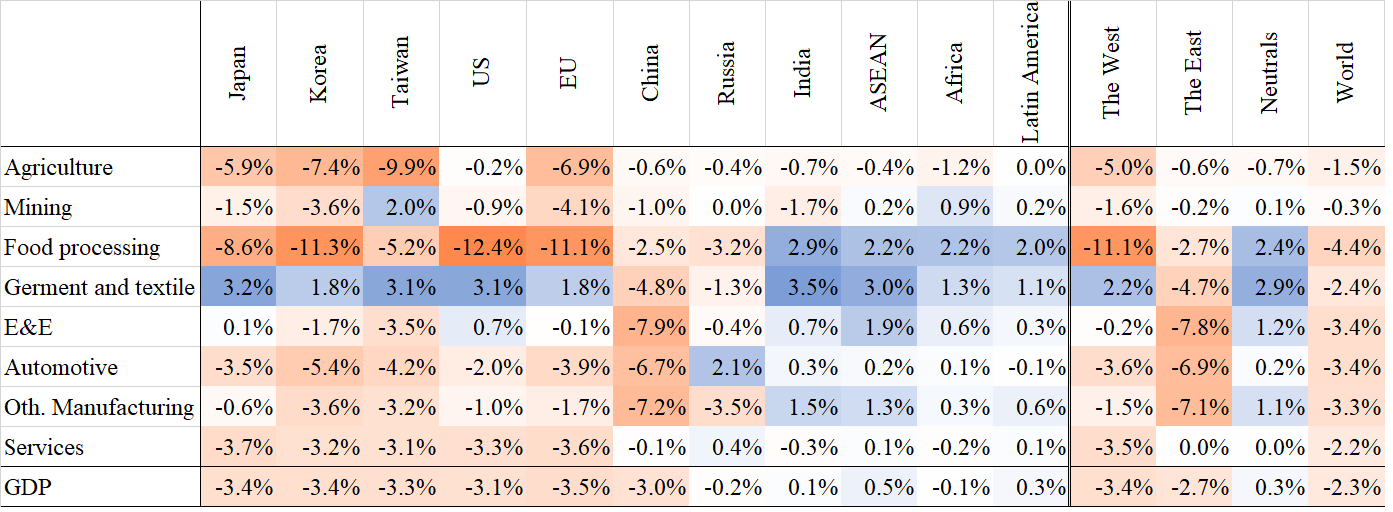

Estimation Results for Scenario 1

Under Scenario 1, the impact on the global economy is −2.3% (approximately US$ 2.7 trillion), while the impacts on Japan, the U.S., the EU, and China range from −3.0% to −3.5%. Additionally, the impact on the Western camp is −3.4%, and that on the Eastern camp is −2.7%, while the impact on the neutral countries is +0.3% (see Table 1 and Figure 1). The profit of the latter countries is because they can still trade with both camps, despite their disputes. Meanwhile, the negative impact on Russia is mitigated since the country is in the same camp as China, the second-largest economy in the world.

Table 1. Economic Impacts of Scenario 1 (2030, compared with the baseline scenario)

Source: Calculation by the author using the IDE-GSM (Kumagai et al. 2023b)

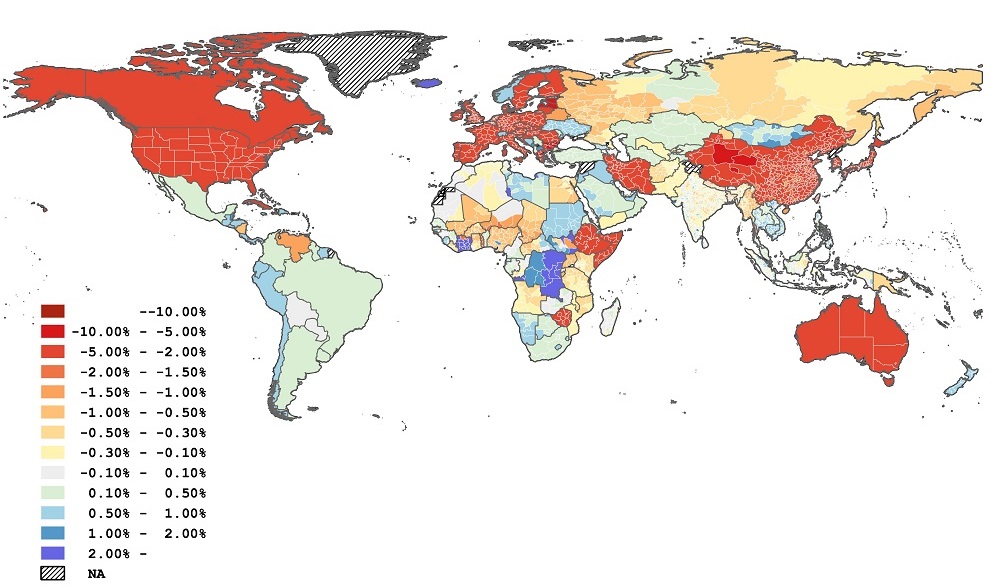

Figure 1. Economic Impacts of Scenario 1 (2030, compared with the baseline scenario)

Source: Calculation by the author using the IDE-GSM (Kumagai et al. 2023b)

Note: The boundaries on the map are based on gadm.org and do not imply endorsement

or judgment by the IDE or JETRO on the attribution of sovereignty.

The magnitude of the impact by industry depends on the production location and substitutability of goods. Specifically, the Western camp would see a positive impact on the clothing and textile industry, mainly in the form of domestic substitution for imports from China. Meanwhile, the impact on the electronics and electrical machinery industries (E&E) would not be as significant in the Western camp, since the primary producers are in Japan, the U.S., Europe, South Korea, and Taiwan. Conversely, China (separated from the major producers in the Western camp) would see a significant negative impact of −7.9%. The Western camp would also experience a significant negative impact in the agriculture and food processing industries, where it is difficult to substitute certain products from specific countries.

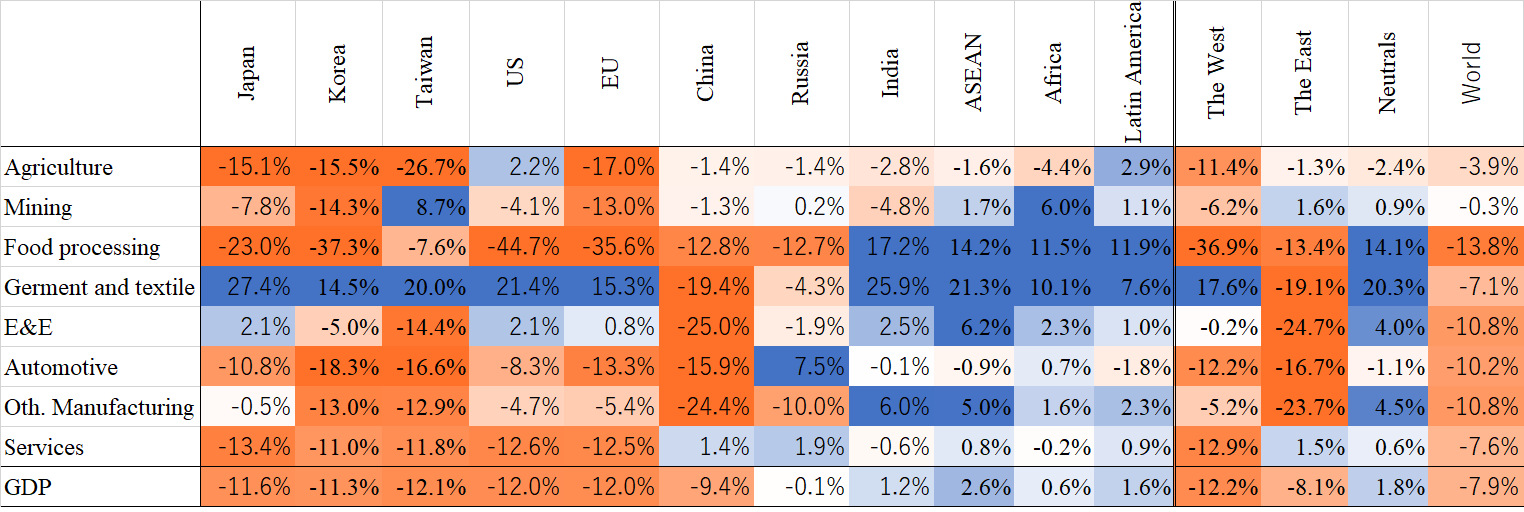

Estimation Results for Scenario 2

Under Scenario 2, the impact on the global economy is −7.9% (approximately US$ 8.7 trillion), which is more significant than that in Scenario 1. By country, the negative impact on Japan, China, and the U.S. is −11.6%, −9.4%, and −12.0%, respectively. Moreover, the impact on the Western camp is −12.2%, that on the Eastern camp is −8.1%, and that on the neutral countries is +1.8% (see Table 2 and Figure 2). Looking at the impacts by industry, the trend is almost the same as that in Scenario 1, but the magnitude of the impacts is several times larger.

Table 2. Economic Impacts of Scenario 2 (2030, compared with the baseline scenario)

Source: Calculation by the author using the IDE-GSM (Kumagai et al. 2023b)

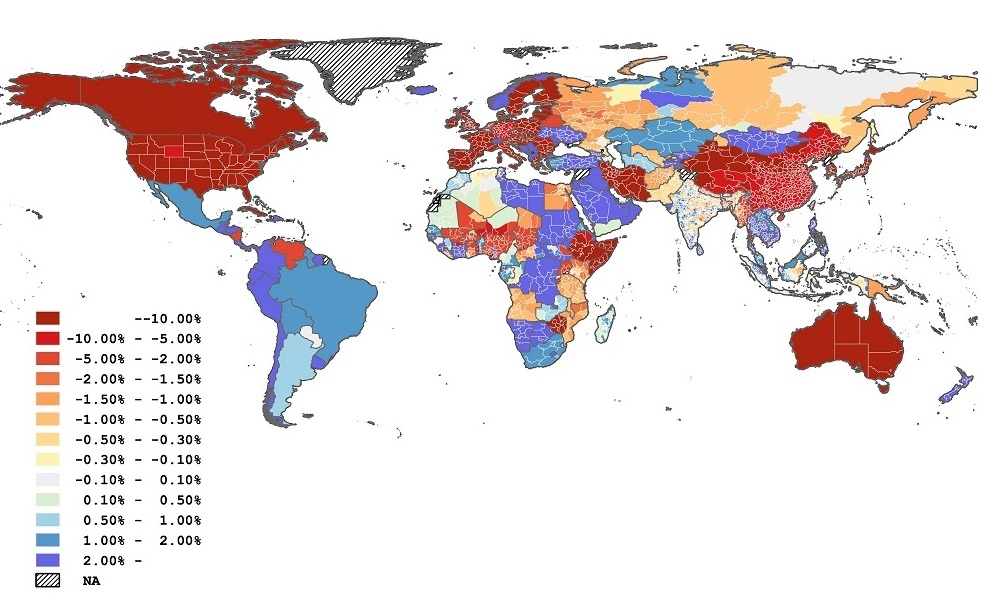

Figure 2. Economic Impacts of Scenario 2 (2030, compared with the baseline scenario)

Source: Calculation by the author using the IDE-GSM (Kumagai et al. 2023b)

Note: The boundaries on the map are based on gadm.org and do not imply endorsement

or judgment by the IDE or JETRO on the attribution of sovereignty.

Conclusions

Due to the difference in economic size between China and Russia, the division of the world around the U.S.-China axis would have a significantly greater impact on the global economy than the confrontation following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In global decoupling, policymakers should consider economic costs, such as the impact of disrupted trade in goods that cannot be substituted, alongside national security. This is because both camps would suffer adverse effects in response to the decoupling.

Moreover, even if both camps intensify their decoupling responses, it would not isolate the other camp from the rest of the world because neutral countries would still profit from the disputes between the two camps. This is because the more profound the conflict between the two camps, the greater the advantages of being neutral.

The implication of the findings is that countries around the world must make realistic judgments in regard to “economic security” and the procurement of critical goods from their own countries and from friendly countries. In particular, the negative economic impact of impeding trade in goods that cannot be substituted for one another is significant.

Notes

- We created additional scenarios with the cooperation of the television program, “NHK Special: The Century of Turmoil” (konmei no seiki).

- By changing trade costs, such as tariffs, non-tariff barriers, and transportation costs, the IDE-GSM can simulate and analyze changes in the GDP for each country and region through changes in the supply and demand of goods, prices, population, and industrial concentration. For details on the model and parameters, see Kumagai et al. (2023a).

- The foreign policy similarity index in Góes and Bekkers (2022) was used as a reference.

- See Kumagai et al. (2023a) for a specific setting within the simulation of sanctions against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- Additional non-tariff barrier rates are assumed to be the same as the U.S. tariff rates raised in 2018–2019 during the U.S.-China trade war. They include 14.3% for agriculture, 16.3% for mining, 11.7% for food processing, 14.5% for textiles and garments, 18.3% for electronics and electrical machinery, 21.3% for automobiles, and 16.7% for other manufacturing sectors. For the service sector, 16.2% (the average for all industries) was applied.

References

Góes, Carlos., and Eddy Bekkers. 2022. “The Impact of Geopolitical Conflicts on Trade, Growth, and Innovation.” WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2022-09. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd202209_e.pdf

Kumagai, Satoru, Kazunobu Hayakawa, Ikumo Isono, Toshitaka Gokan, Souknihlan Keola, Kenmei Tsubota, and Hiroya Kubo. 2023a. “Simulating the Decoupling World under Russia's Invasion of Ukraine: An Application of IDE-GSM.” IDE Discussion Paper no. 874. https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Reports/Dp/874.html

Kumagai, Satoru, Kazunobu Hayakawa, Toshitaska Gokan, Ikumo Isono, Souknilanh Keola, Kenmei Tsubota, and Hiroya Kubo. 2023b. “The Impact of ‘Decoupling’ on the Global Economy—An Analysis by IDE-GSM” [In Japanese]. IDE Square, February 2023.

https://www.ide.go.jp/Japanese/IDEsquare/Eyes/2023/ISQ202320_004.html(last accessed on April 3, 2023).

* Thumbnail photo: Globe Series (dem10/ E+/ Getty Images)

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions to which the author is attached.