IDE Research Columns

Column

Student Movement in Chile: A Part of or a Protester Against Political Elites?

Kota MIURA

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

May 2025

The crisis of representative democracy has resulted in diminished trust in political parties and has also affected civil society organizations. While traditional trade unions and interest groups associated with political parties have weakened, social movements have become increasingly active in response to dissatisfaction among citizens. This study examines whether political distrust leads to trust or distrust in the student movement in Chile, a country that has recently experienced a crisis of representative democracy. Historically, the student movement has been aligned with political parties but it has regained momentum since the 2000s. The findings indicate that citizens who distrust political parties also distrust the student movement, perceiving it as part of the political elite. Conversely, those who oppose the government are more likely to express trust in the movement when students actively protest against government actions. These results underscore the challenges civil society organizations face in sustaining legitimacy in society and suggest that the adaptability of student movements to sociopolitical changes over time may help sustain their influence in the long run.

Political Distrust and Civil Society Organizations

In the 21st century, people have experienced a crisis of representative democracy worldwide. A key indicator is the erosion of public trust in political parties, which serve as foundational institutions of representative democracy (Valgarðsson et al. 2025). The ramifications of this extend beyond the political domain and into civil society organizations (van Biezen and Poguntke 2014). During periods of heightened political distrust, traditional trade unions and interest groups that have been linked to political parties have weakened, whereas social movements have emerged as increasingly active actors in response to mounting public dissatisfaction. In short, the effects of the crisis of representative democracy on civil society organizations are not uniform. Surviving and maintaining strength in an era of political distrust are important issues for civil society organizations to ensure that a channel exists through which citizens’ voices are reflected in politics. Accordingly, a nuanced understanding of the complex relationship between political distrust and civil society organizations is essential.

Political Distrust in Chile

Historically, Chile has maintained relatively stable and institutionalized party politics since the early 20th century. Although a military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990 disrupted this continuity, the country returned to democracy in 1990 and has since experienced continued political stability. Following democratization, Chilean politics was dominated by two major political party coalitions, a situation facilitated by a unique electoral system known as the binominal system. While these coalitions contributed to political stability, they upheld the neoliberal framework instituted under the military government, albeit with incremental expansions in social policies. Although socioeconomic inequality is on the decline, Chile remains one of the most unequal countries among OECD members, and public dissatisfaction with inequality persists. For Chileans, party politics has failed to present a viable alternative to neoliberalism. Consequently, political distrust has increased, and representative democracy has remained in crisis since the 2010s (Castiglioni and Rovira Kaltwasser 2016).

Political distrust among the Chilean population is twofold: one directed at political parties and the other against the government. Political parties, expected to represent the people and formulate policies, are often perceived as an elite class by the citizens, failing to represent citizens’ interests. Citizens may also disapprove of the government when they feel unrepresented or dissatisfied with its policies. In the past, the Chilean government used to maintain relatively high approval rates even if there was a lack of trust in political parties. In recent years, however, approval ratings have steadily fallen shortly after new governments form and have remained low.

Student Movement in Chile

The Chilean student movement has significantly influenced politics and society for over a century (Garretón y Martínez 1985). Like trade unions, it is one of Chile’s traditional civil society organizations. Historically, the movement has been closely linked to political parties and has collaborated with them to protect students’ interests within the established political framework. It has also served as a platform for the training of future political leaders, and many prominent politicians starting their careers through student activism.

Over the past 25 years, the student movement has distanced itself from political parties and has responded to widespread citizens’ distrust toward institutional politics (Somma and Donoso 2021), ahead of other traditional civil society organizations. It has tried to function as an autonomous social movement by working more closely with grassroots activities and a broader civil society. The large-scale, nationwide student protests of 2011 highlighted this shift. Throughout the 2010s, the student movement protested directly against the government and indirectly against the two abovementioned coalitions, calling for an end to neoliberalism. These widely-supported protests addressed broad issues—such as socioeconomic inequality and political reform—thus becoming a driving force for political and social changes during the 2010s.

Analysis of Public Opinion Poll Data

This study explores whether political distrust leads to distrust or trust in the student movement. Citizens distrustful of political parties may also distrust the student movement due to its historical ties to these parties. On the other hand, as the student movement opposes the government and political parties through protests, it may gain the trust of citizens who do not support the government or distrust political parties.

Using public opinion data from the Center of Public Studies (Centro de Estudios Públicos) from 2011, 2012, 2014, and 2016, this study examines the relationship between political distrust and trust in the student movement. Although the Chilean student movement organized protests throughout the 2010s, the intensity of these protests varied from year to year. This intensity acts as a visible indicator that the student movement confronts the government and political parties. In turn, this visibility may influence whether the movement is perceived as a channel for political distrust among citizens.

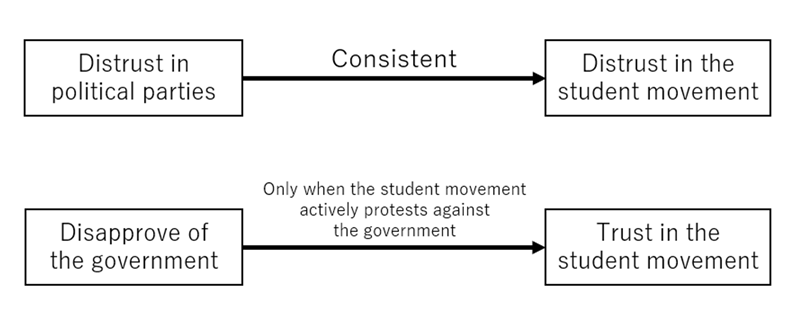

Figure 1 summarizes the findings of the analysis. First, the results consistently demonstrated in each year analyzed that citizens who do not trust political parties are more likely to distrust the student movement as part of the same elite. However, in years of intense protest activities, the relationship between distrust in political parties and distrust in the student movement is weaker. While political parties are an indirect target of protests, these actions may help mitigate the negative effect of political distrust on the student movement. Second, in years when the student movement actively protests the government, people who disapprove of the government tend to place more trust in the student movement, suggesting that the movement channels political distrust.

Figure 1. How Political Distrust Shapes Perceptions of the Student Movement

Source: Created by the author.

Implications

Civil society organizations closely linked with political parties risk losing public trust in the current crisis of representative democracy. Simply distancing from political parties is insufficient to regain public trust; clear opposition to political parties may also be necessary. Strategies that maintain social legitimacy and political influence while addressing citizens’ evolving expectations are crucial. These findings suggest that student movements may be relatively better positioned to respond to these challenges than other civil society organizations. Since there are constant cycles of people coming in and out due to generational changes, it may be easier for student movements to adapt their strategies to sociopolitical changes over time. While not the only factor, the ability to adapt to political distrust is likely a critical element in enabling civil society organizations to remain influential in contemporary democracies.

Author's Note

This column is based on the following paper: Miura, Kota. 2024. “Part of Political Elites or a Protester against Them? Analysis of Trust in the Student Movement in Chile in the Era of Political Distrust.” [in Japanese]. Ajia Keizai 65 (3): 97–125. https://doi.org/10.24765/ajiakeizai.65.3_97

References

Castiglioni, Rossana, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2016. "Challenges to Political Representation in Contemporary Chile." Journal of Politics in Latin America 8 (3): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X1600800301

Garretón, Manuel Antonio, y Javier Martínez. 1985. El movimiento estudiantil: conceptos e historia. Santiago: Ediciones SUR.

Miura, Kota. 2024. “Part of Political Elites or a Protester against Them? Analysis of Trust in the Student Movement in Chile in the Era of Political Distrust.” [in Japanese]. Ajia Keizai 65 (3): 97–125. https://doi.org/10.24765/ajiakeizai.65.3_97

Somma, Nicolás, and Sofia Donoso. 2021. "Chile’s Student Movement: Strong, Detached, Influential—And Declining?" In Student Movements in Late Neoliberalism: Dynamics of Contention and Their Consequences, edited by Lorenzo Cini, Donatella della Porta, and César Guzmán-Concha: 241-267. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75754-0_10

Valgarðsson, Viktor, Will Jennings, Gerry Stoker, Hannah Bunting, Daniel Devine, Lawrence McKay, and Andrew Klassen. 2025. "A Crisis of Political Trust? Global Trends in Institutional Trust from 1958 to 2019." British Journal of Political Science 55: e15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000498

van Biezen, Ingrid, and Thomas Poguntke. 2014. "The Decline of Membership-Based Politics." Party Politics 20 (2): 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813519969

* Thumbnail image: Student demonstration in Santiago, Chile, opposing neoliberal educational policies (photo by the author in 2012)

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

©2025 Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO)

This column is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed