IDE Research Columns

Column

Dowry and Women’s Empowerment: Why does the Practice Remain in South Asia?

Momoe MAKINO

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

October 2022

Dowry is the transfer of cash, jewelry, and other valuable assets from the bride’s family to the groom’s family at the time of marriage. Dowry is prohibited in India and Bangladesh and restricted in Pakistan. However, these legal measures are not effective; in fact, the practice of dowry is widespread in South Asian countries. It is my argument that people are incentivized to continue observing the seemingly gender-discriminatory practice of dowry, despite its illegality. Simply banning dowry may lead to unexpected negative effects on women’s welfare. Dowry will likely only disappear when it is viewed as unnecessary. Women’s empowerment, specifically through participation in paid-work and guarantees of property rights, may be the key to discouraging the practice.

Dowry is believed by many to be a cause of gender discriminatory practices, including sex-selective abortion, female infanticide, lower educational attainment by girls, child marriage, and domestic violence and murder. For example, one clinic advertisement reads, “Better Rs. 500 now [for the abortion of a female fetus] than Rs. 500,000 later [in dowry]” despite the legal ban on using ultrasound for sex determination. “Dowry murder” is a crime against a woman in connection with demand for dowry, committed by her husband or his relatives; such cases appear in local newspapers every day in South Asia. Given the potential for these detrimental consequences, dowry is legally prohibited or restricted. However, these legal measures remain hopelessly ineffective. Why do people continue observing the dowry practice despite the legal ban? My research seeks to answer this question based on both existing and unique new datasets.

The Nature of Dowry

As for the nature of dowry, theoretical studies have been actively conducted. Based on Becker (1985), dowry is often considered as the price to clear the marriage market. The price model predicts that an undersupply of grooms in the marriage market or a better quality of groom leads to a higher amount of dowry. According to this view, highly educated daughters and their better income-earning opportunities may discourage the dowry practice.

Although not necessarily mutually exclusive, another explanation for dowry is that it represents the bequest that parents are willing to offer to their daughter at the time of marriage. In a society where women’s inheritance and property rights are not fully assured, dowry may function as the only source of protection for women. According to this view, providing women with equal inheritance rights as their brothers may reduce or eliminate the use of dowry.

These theoretical explanations of dowry suggest that increasing women’s paid-work participation and/or enhancing women’s inheritance and property rights might reduce the practice of dowry. One of the major empirical problems concerning the nature of dowry is endogeneity and confounding factors determining the amount of dowry. Increasing the earning potential and education of brides may lead to a lower dowry according to the price model. However, such higher quality brides are often matched to the higher quality groom, who may demand a higher dowry. Also, a better-educated bride is more likely to come from a better-off household that can afford a higher dowry.

Moreover, the biggest obstacle to conducting empirical research on dowry is the lack of reliable data. This is not surprising because dowry is an illegal practice in India and Bangladesh, and although it is not illegal in Pakistan, dowry data are usually collected retrospectively and are subject to recall errors.

Women’s Paid-Work Participation May Decrease the Practice of Dowry

It is an empirical question whether the bride’s paid-work participation lowers the amount of her dowry because it can be affected by many confounding factors, as the above example shows. Working brides may not have to pay a higher dowry because they can financially contribute to the groom’s family in the patrilocal society. However, women working outside the home are often stigmatized in the South Asian context, and thus may be considered of lower quality in the marriage market.

To empirically investigate this question, I conducted a survey in rural Pakistan (Makino 2021). The survey’s unique feature asked the expected amount of dowry, bride price, and ceremony expenses, for all unmarried daughters and their siblings. Using the expected amount can avoid recall errors, which are a major problem when collecting information retrospectively. The results showed that the bride’s paid-work participation lowers the expected amount of dowry.

Parent May Voluntarily Offer Dowry

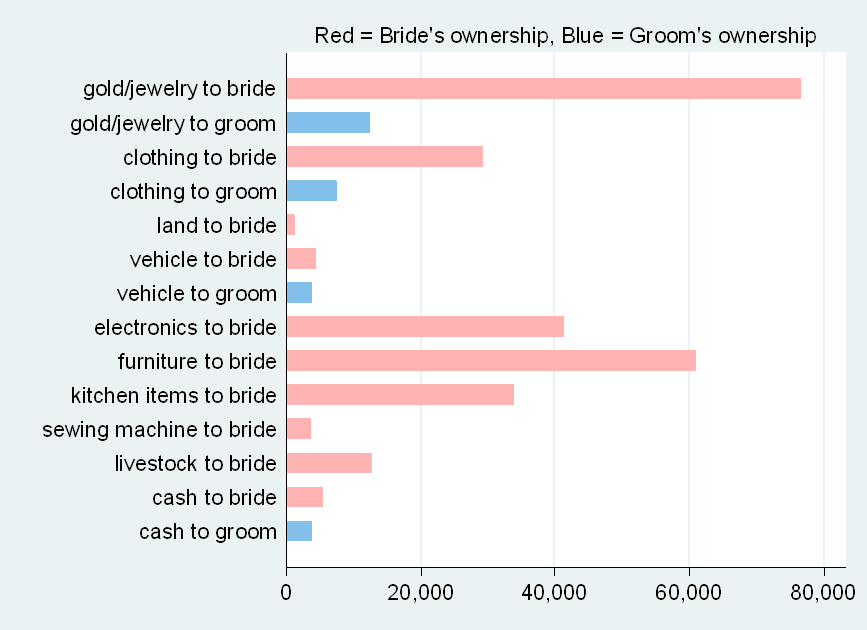

Previously, we conducted a unique household survey in rural Pakistan to explore the nature of dowry by tackling the issue of data unavailability (Makino 2019a). The survey was carefully designed to collect accurate information on dowry and minimize recall errors by asking for item-specific amounts of dowry (Figure 1) and ceremony-related expenses concerning the respondents’ own marriage, their siblings’ marriages, and typical marriages in the community. We also verified the amounts with village informants and neighbors because dowry items are showed off at the time of marriage ceremony to the neighbors and villagers and their values are public information.

The estimation results suggest that the nature of dowry in the Pakistani marriage is more trousseau (i.e., the personal possessions of the bride) than the price that is cleared in the marriage market. That means, parents are willing to offer a higher amount of dowry to their daughters to ensure better treatment and living conditions for their daughters after moving into the husband’s home upon marriage. We found that the dowry amount, especially the values of furniture, electronic appliances, and kitchenware, is positively associated with the enhanced bargaining position of the wives in the marital household.

Dowry May Compensate for the Lack of Women’s Inheritance Rights

The Hindu Succession Act was amended in 2005, and Hindu women were legally provided equal inheritance rights with their brothers. This change took effect throughout all of India, but some relatively progressive states had already amended the Act at the state level to ensure women equal inheritance rights, including Kerala in 1976, Andhra Pradesh in 1986, Tamir Nadu in 1989, and Maharashtra and Karnataka in 1994. By utilizing the difference in the timing of the state’s enactment of equal inheritance and the timing of women’s marriages, I investigated the heterogeneity in the association between the dowry practice and women’s empowerment measures (Makino 2019b). The dataset used is the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS), in which respondents provided the usual amount of dowry prevalent in their community.

I found a positive association between the amount of dowry and women’s empowerment measures only for women who did not have equal inheritance rights with their brothers. This finding suggests that dowry is not as necessary for women to enhance their status in the marital household if they have equal inheritance rights with their brothers. In a way, dowry may exist to compensate for the lack of women’s inheritance rights and serves as a measure to enhance their bargaining position in the marital household.

Policy Implication

When a practice such as dowry is widespread in society despite its legal prohibition, it is necessary to examine the reasons why people continue the practice. When women lack property rights and paid-work opportunities, dowry may be the only asset available to women and their only source of protection in the marital household. Without protective measures for women, dowry will likely continue, and to the extent a ban on dowry is effective at reducing or eliminating dowry, it may worsen the welfare of women.

References

Becker, Gary S. 1985. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Makino, Momoe. 2019a. “Marriage, Dowry, and Women’s Status in Rural Punjab, Pakistan.” Journal of Population Economics 32 (3): 769–97.

———. 2019b. “Dowry in the Absence of the Legal Protection of Women’s Inheritance Rights.” Review of Economics of the Household 17 (1): 287–321.

———. 2021. “Female Labour Force Participation and Dowries in Pakistan.” Journal of International Development 33 (3): 569–93.

About the Author

Momoe Makino specializes in development microeconomics, household economics, and population economics. Her research papers published in peer-reviewed journals include “Labor Market Information and Parental Attitudes toward Women Working Outside the Home: Experimental Evidence from Rural Pakistan” (Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming) and “Heterogeneous Impacts of Interventions Aiming to Delay Girls' Marriage and Pregnancy Across Girls' Backgrounds and Social Contexts” (with Ngo TD, Psaki S, Amin S, and Austrian K, Journal of Adolescent Health, 2021). She received her Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Washington.

*Thumbnail image: Mayur Dave/ EyeEm/ Candid Photograph of Indian Wedding Ceremony (Getty Images)

**The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.