IDE Research Columns

Column

What Makes One’s Job Interesting? A Cross-Country Comparison

Yoko ASUYAMA

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

September 2022

Individuals who believe that their job is interesting work harder, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to quit their job. Job interestingness, i.e., how much one finds his/her job interesting, is expected to enhance voluntary learning in the workplace. Despite the importance of job interestingness, empirical studies on its determinants are scarce. This article explores this issue and indicates that the key determinants of job interestingness vary between countries or country groups in terms of their weight. A good relationship with management and colleagues is a very important determinant in Japan, whereas job autonomy is more significant in other high-income countries. A job’s economic meaning has much more influence in middle- and low-income countries. These results imply that the effective ways to make a job interesting are likely to differ across cultures, work organizations, and developmental stages.

Why Should We Care about Job Interestingness?

“[I]nterest is a powerful motivator.” Children voluntarily learn about their world through the activities that they find interesting (Deci 1992, p. 43). In educational psychology, the importance of interest has been recognized: interest in a certain subject promotes learning and academic performance (O’Keefe, Horberg, and Plante 2017). In the workplace, greater interest in a job is expected to promote employees’ voluntary learning, which is crucial in today’s rapidly changing technological world and extended years of work due to rising life expectancies. Asuyama (2021, Online Appendix B) found that individuals who think that their job is interesting work harder, have greater job satisfaction and organizational commitment, are more willing to continue working at their current organization, and enjoy better mental health. Thus, higher job interestingness is beneficial for both employees and firms.

How Many People Find Their Job Interesting?

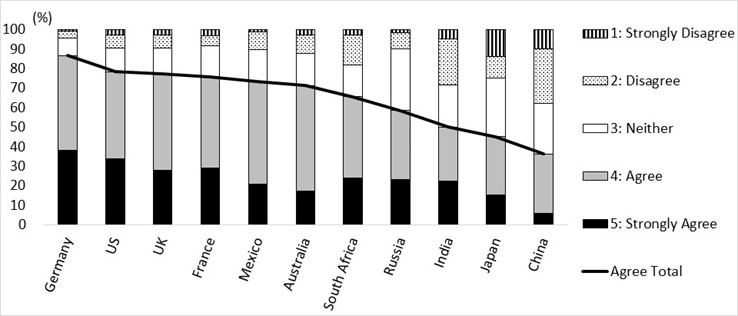

The answer to this question is that it varies substantially by country. Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of workers who agree or disagree that their job is interesting in several G20 countries, the data for which were available in 2015. The proportion of workers who find their job interesting tends to be greater in high-income countries, excluding Japan. A total of 86.8% of German and 78.6% of American workers agree that their jobs are interesting. By contrast, the corresponding figures are relatively low in lower-income countries as well as Japan.1 Only 45.1% of Japanese and 36.3% of Chinese workers agree that their jobs are interesting.

Figure 1. Do You Agree That Your Job Is Interesting?

Answers across the Available Data for G20 Countries in 2015

Note: This graph shows the percentage of workers in each country who agree or disagree that their job is interesting.

Source: Based on Figure B1 in Asuyama (2021), which is computed from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) in 2015.

What explains these differences? To answer this question, we first must identify the factors that determine job interestingness.2 Empirical studies on the determinants of interest have been developed in the field of educational psychology (Renninger and Hidi 2011; O’Keefe and Harackiewicz 2017). Similar studies in the workplace context, however, are limited. In the field of economics, job interestingness is found to be an important determinant of job satisfaction (Sousa-Poza and Souza-Poza 2000; Benz and Frey 2008; Krekel, Ward, and De Neve 2019). However, job interestingness is also a subjective measure, so how to make a job interesting remains a black box. To fill this gap in the literature, Asuyama (2021) quantified the importance of key determinants of job interestingness for the first time.

Key Determinants of Job Interestingness

Based on the psychology literature, Asuyama (2021) emphasized these seven key job characteristics as factors that affect job interestingness.3

- Competence: Feeling capable, which can be experienced by developing and effectively exercising one’s skill in the workplace.

- Autonomy: Feeling uncoerced in one’s behavior, which can be experienced when one enjoys job autonomy and works independently.

- Relatedness: Feeling connected to others, which can be experienced through good interpersonal workplace relationships.

- Prosocial meaning: Feeling that one’s own job helps others or is useful to society.

- Economic meaning: Feeling that one’s own job leads to pecuniary rewards such as a higher income and a greater possibility of promotion, as well as a lower probability of being laid off.

- Pressure: Feeling pressure or constraints in the workplace such as work–life conflict and deadline pressure.

- Interest match: Feeling that one’s own interests and the actual work environment are aligned.

Based on the literature, it is expected that (1) “pressure” will lower job interestingness, (2) “economic meaning” will either raise or lower job interestingness, and (3) the remaining five determinants increase job interestingness.

The Key Determinants of Job Interestingness Vary across Countries

Using worker-level data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) for 1997, 2005, and 2015, Asuyama (2021) empirically confirmed that “pressure” decreases job interestingness, whereas the remaining six job characteristics generally increases job interestingness, regardless of country.

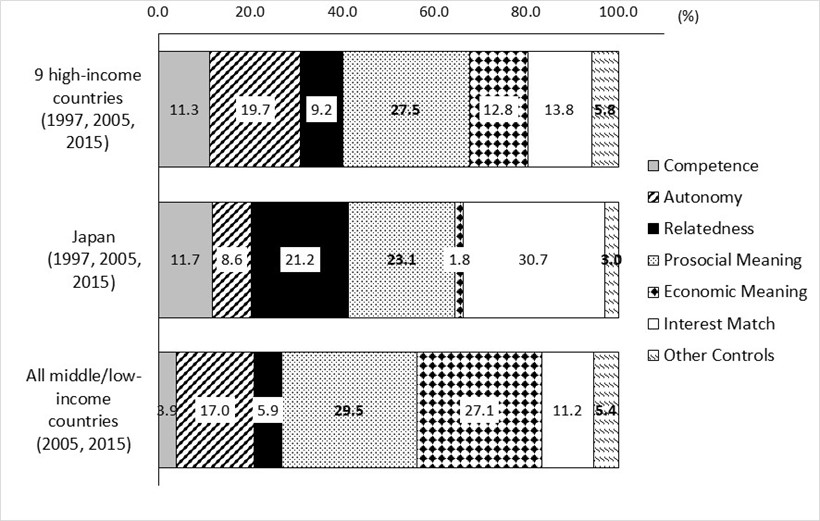

Figure 2 illustrates the relative importance of the key job characteristics that explain the variations in job interestingness among workers in high-income countries (i.e., nine countries excluding Japan), Japan, and middle- and low-income countries. It is calculated by applying a regression-based inequality decomposition technique (Fields 2003) to the ISSP data (for 2005 and 2015 for middle- and low-income countries only). Each number in the bar graph indicates the percentage of job interestingness variation explained by each determinant. Note that 100% is set as the variation in job interestingness after purging the variation explained by unobservable factors (“residuals”) and differences in country, survey year, and survey mode.4 Among the seven key determinants, “pressure” is not depicted in this figure because information on this variable is not available for all three years.

As shown in Figure 2, all three country groups share prosocial job meaning and job interest match, which are two of the four most important predictors of job interestingness. In both high-income and middle- and low- income country groups, autonomy and a job’s economic meaning are also ranked in the top four; however, the explanatory power of a job’s economic meaning (such as a higher income and greater possibility of promotion) is much larger in middle- and low-income countries. Japan is unique in that the explanatory power of relatedness (i.e., good relationships with management and colleagues) is much higher, whereas that of economic meaning is much lower.

Figure 2. Explanatory Power of Each Determinant to Job Interestingness

Note: 100% is set as equal to the variation in job interestingness after purging the variation explained by unobservable factors (“residuals”) and differences in country, survey year, and survey mode. The nine high-income countries (excluding Japan) are those that participated in all three survey waves, which include France, Germany, Great Britain (UK), Israel, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States (US). “Other Controls” include various worker characteristics and job characteristics that affect job interestingness.

Source: Based on Figures 2 and B4 in Asuyama (2021), which is computed from ISSP in 1997, 2005, and 2015.

Asuyama (2021) showed that the lower explanatory power of job autonomy in Japan is partly attributable to the fact that the country has a comparatively collective culture. She also found that the greater importance of relatedness in Japan is associated with the limited work independence of Japanese workers. It is very likely that Japanese workers must coordinate with co-workers frequently and thus work less independently as a result of Japan’s group- and consensus-based decision-making system.

Implications

Enhancing job interestingness increases worker well-being and job performance. However, empirical studies on how to make a job more interesting are still limited. The above results suggest that policies such as informing employees about how their jobs are socially meaningful and enhancing a job’s interest-matching qualities using public or private job matching services might be effective for improving job interestingness in most countries. Conversely, the results also imply that the effective ways to make a job more interesting are likely to differ across cultures, work organizations, and development stages.

Author’s Note

This column is based on Asuyama, Yoko. 2021. “Determinants of Job Interestingness: Comparison of Japan and Other High-Income Countries” Labour Economics 73: 102082.

Notes

- The income level is based on Asuyama (2021), who used the World Bank’s criterion for fiscal year 1997.

- This column examines the determinants of job interestingness. Asuyama (2021) additionally investigated why there are fewer interesting jobs in Japan than in other high-income countries.

- These key determinants are selected based on psychology studies such as Deci (1992), Krapp (2005), Ryan and Deci (2018), Renninger and Hidi (2011), Thoman, Sansone, Greeling (2017), Holland (1997), and Nye, Bhatia, and Prasad (2019).

- The purged part (mostly “residuals”) originally explained 60%–70% of the entire variation in job interestingness.

References

Asuyama, Yoko. 2021. “Determinants of Job Interestingness: Comparison of Japan and Other High-Income Countries.” Labour Economics 73: 102082.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.102082

Benz, Matthias, and Bruno S. Frey. 2008. “The Value of Doing What You Like: Evidence from the Self-employed in 23 Countries.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 68(3/4): 445–55.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2006.10.014

Deci, Edward L. 1992. “The Relation of Interest to the Motivation of Behavior: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” In The Role of Interest in Learning and Development, edited by K. Ann Renninger, Suzanne Hidi, and Andreas Krapp, 43–70. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Fields, Gary. 2003. “Accounting for Income Inequality and Its Change: A New Method, with Application to the Distribution of Earnings in the United States.” In Worker Well-Being and Public Policy, edited by S.W. Polachek (Research in Labor Economics 22), 1-38. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-9121(03)22001-X

Holland, John L. 1997. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments, 3rd ed. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Krapp, Andreas. 2005. “Basic Needs and the Development of Interest and Intrinsic Motivational Orientations.” Learning and Instruction 15(5): 381–95.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.007

Krekel, Christian, George Ward, and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve. 2019. “What Makes for a Goof Job? Evidence Using Subjective Wellbeing Data.” In The Economics of Happiness, edited by Mariano Rojas, 241–68. Cham: Springer.

Nye, Christopher D., Sarena Bhatia, and Joshua J. Prasad. 2019. “Vocational Interests and Work Outcomes.” In Vocational Interests in the Workplace: Rethinking Behavior at Work, edited by Christopher D. Nye and James Rounds, 97–128. New York: Routledge.

O’Keefe, Paul A., and Judith M. Harackiewicz eds. 2017. The Science of Interest. Cham: Springer.

O’Keefe, Paul A., E.J. Horberg, and Isabelle Plante. 2017. “The Multifaceted Role of Interest in Motivation and Engagement.” In The Science of Interest, edited by Paul A. O’Keefe and Judith M. Harackiewicz, 49–67. Cham: Springer.

Renninger, K. Ann, and Suzanne E. Hidi. 2011. “Revisiting the Conceptualization, Measurement, and Generation of Interest.” Educational Psychologist 46(3): 168–84.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.587723

Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2018. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

Sousa-Poza, Alfonso, and Andres A. Sousa-Poza. 2000. “Well-being at Work: A Cross-National Analysis of the Levels and Determinants of Job Satisfaction.” Journal of Socio-Economics 29(6): 517–38.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(00)00085-8

Thoman, Dustin B., Carol Sansone, and Danielle Geerling. 2017. “The Dynamic Nature of Interest: Embedding Interest Within Self-Regulation.” In The Science of Interest, edited by Paul A. O’Keefe and Judith M. Harackiewicz, 27–47. Cham: Springer.

*Thumbnail image: olaser/Workers working late. Tall building reflected - stock photo (Getty Images)

**The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.