Myanmar Migrants to Thailand and Implications to Myanmar Development

Policy Review on Myanmar Economy

No.7

Supang Chantavanich

(Professor Emeritus at Faculty of Political Science and Director of Asian Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies at Chulalongkorn University.)

(Professor Emeritus at Faculty of Political Science and Director of Asian Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies at Chulalongkorn University.)

October 2012

PDF (237KB)

PDF (Burmese) (767KB) BUSINESS , Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commers & Industry, Vol.13 No.1, January 2013.

Current Situation of Migration from Myanmar in Thailand

Cross-border migration of people from Myanmar to Thailand has a long history spanning many decades. In the past, ethnic groups who lived along the Thai-Myanmar borders, especially the Karen, the Mon and the Shan, spontaneously crossed the borders to visit friends, buy goods or seek healthcare services in the area regularly. During the military regime administration in the 1980s, the borders were quiet with no official crossings although the ethnic people commuted unofficially. On the other hand, a significant number of asylum-seekers who were ethnic minorities fighting against the Myanmar government started to enter Thailand to take refuge in that decade. The Thai government agreed to host a big number of approximately 140,000 political asylum-seekers in nine temporary shelters in four provinces at border areas. Another wave of migrants arrived in the 1990s for economic reasons. They were both ethnic and Burmese people. Since 1992, Thailand has started to officially recognize the arrival and the entrance of migrants from Myanmar into Thailand’s labour market. The first registration of migrants as unskilled workers began that year.

From 1992 to 2012, the influx of migrant workers from Myanmar has continued. Economically, Thailand has a pull factor being a destination where the local labour market needs unskilled workers in many sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing and some service work, especially domestic and construction work. Many Thai workers shun to do work in these sectors. In addition, the wages in Thailand are ten times higher than what workers can find in Myanmar, partly due to the Kyat’s (Myanmar currency) depreciation and the Baht’s (Thai currency) strength. On the Myanmar side, slow economic growth, unemployment and forced labour for government development projects such as railway construction pushed both Burmese and ethnic groups to come to Thailand for job opportunities and higher wages. Currently, the number of migrant workers from Myanmar has risen to more than 2 million. They fall under three categories: registered workers, those who go through national verification, and those who are recruited directly and formally from Myanmar.

Among the three categories, labour migration management in Thailand first implemented the annual registration of a migrant workers policy. Since 2010, a second management policy has been launched to request workers to go through the national verification process, which involves cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar according to the MOU on Cooperation in Employment signed in 2003. In 2009, a third policy of formal recruitment was started and it continues until the present.

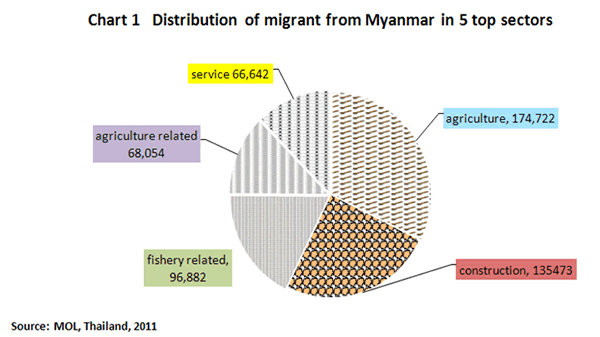

Migrant workers are mainly hired in the sectors of agriculture, construction, fishery and domestic work (see Chart 1). Although the Thai government announced that only unskilled migrant workers or labourers can be employed, some workers have entered into less-skilled or semi-skilled work such as manufacturing (garments, plastics, paper), services and sales, transport and trade. As the background of most workers was as a farmer, they learn some new skills while working in Thailand. Initial results from the survey of migrant workers in Samut Sakorn, Tak and Bangkok indicated that 77% of respondents confirmed learning skills, i.e. manufacturing of garments and plastics, flower cutting in agriculture, fishery-related work and services such as sales and domestic work, including Thai language skills.

However, there is no official policy to train these workers for their skills development. Skilled workers from Myanmar are also employed in Thailand. Although they are not numerous (only about 400 persons), they engage in professional work such as being teachers, university lecturers and health workers.

Direction of Myanmar Economic Development

Looking at economic and political reforms in Myanmar in 2012, it is increasingly clear that the reforms will sustain while ASEAN economic integration is ongoing and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) is scheduled to be launched within three years. The liberalization and deregulation of labour mobility, especially for the professionals including medical doctors, dentists, nurses, engineers, architects and accountants, is in progress. The Mutually Recognized Agreements (MRAs) for all professions were signed by the ministers of trade from all ASEAN members. Myanmar has agreed to the required measures which will be achieved in 2015. In addition, personnel in tourism and hotel businesses may be included among the AEC 2015 labour mobility. Nonetheless, a Myanmar expert indicates that the AEC can bring special dangers to its low-income members, including Myanmar. It can lead to “economic polarization,” where the most talented people will leave the country to take better opportunities and higher rewards in more advanced member countries. Therefore, there are initiatives to strengthen the CLMV countries in playing a more positive role in the AEC and to increase their prospects of benefiting from AEC participation (U Myint, 2011). However, such initiatives may not yet materialize to prevent the brain drain.

Cross-border migration of people from Myanmar to Thailand has a long history spanning many decades. In the past, ethnic groups who lived along the Thai-Myanmar borders, especially the Karen, the Mon and the Shan, spontaneously crossed the borders to visit friends, buy goods or seek healthcare services in the area regularly. During the military regime administration in the 1980s, the borders were quiet with no official crossings although the ethnic people commuted unofficially. On the other hand, a significant number of asylum-seekers who were ethnic minorities fighting against the Myanmar government started to enter Thailand to take refuge in that decade. The Thai government agreed to host a big number of approximately 140,000 political asylum-seekers in nine temporary shelters in four provinces at border areas. Another wave of migrants arrived in the 1990s for economic reasons. They were both ethnic and Burmese people. Since 1992, Thailand has started to officially recognize the arrival and the entrance of migrants from Myanmar into Thailand’s labour market. The first registration of migrants as unskilled workers began that year.

From 1992 to 2012, the influx of migrant workers from Myanmar has continued. Economically, Thailand has a pull factor being a destination where the local labour market needs unskilled workers in many sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing and some service work, especially domestic and construction work. Many Thai workers shun to do work in these sectors. In addition, the wages in Thailand are ten times higher than what workers can find in Myanmar, partly due to the Kyat’s (Myanmar currency) depreciation and the Baht’s (Thai currency) strength. On the Myanmar side, slow economic growth, unemployment and forced labour for government development projects such as railway construction pushed both Burmese and ethnic groups to come to Thailand for job opportunities and higher wages. Currently, the number of migrant workers from Myanmar has risen to more than 2 million. They fall under three categories: registered workers, those who go through national verification, and those who are recruited directly and formally from Myanmar.

Among the three categories, labour migration management in Thailand first implemented the annual registration of a migrant workers policy. Since 2010, a second management policy has been launched to request workers to go through the national verification process, which involves cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar according to the MOU on Cooperation in Employment signed in 2003. In 2009, a third policy of formal recruitment was started and it continues until the present.

Migrant workers are mainly hired in the sectors of agriculture, construction, fishery and domestic work (see Chart 1). Although the Thai government announced that only unskilled migrant workers or labourers can be employed, some workers have entered into less-skilled or semi-skilled work such as manufacturing (garments, plastics, paper), services and sales, transport and trade. As the background of most workers was as a farmer, they learn some new skills while working in Thailand. Initial results from the survey of migrant workers in Samut Sakorn, Tak and Bangkok indicated that 77% of respondents confirmed learning skills, i.e. manufacturing of garments and plastics, flower cutting in agriculture, fishery-related work and services such as sales and domestic work, including Thai language skills.

However, there is no official policy to train these workers for their skills development. Skilled workers from Myanmar are also employed in Thailand. Although they are not numerous (only about 400 persons), they engage in professional work such as being teachers, university lecturers and health workers.

Direction of Myanmar Economic Development

Looking at economic and political reforms in Myanmar in 2012, it is increasingly clear that the reforms will sustain while ASEAN economic integration is ongoing and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) is scheduled to be launched within three years. The liberalization and deregulation of labour mobility, especially for the professionals including medical doctors, dentists, nurses, engineers, architects and accountants, is in progress. The Mutually Recognized Agreements (MRAs) for all professions were signed by the ministers of trade from all ASEAN members. Myanmar has agreed to the required measures which will be achieved in 2015. In addition, personnel in tourism and hotel businesses may be included among the AEC 2015 labour mobility. Nonetheless, a Myanmar expert indicates that the AEC can bring special dangers to its low-income members, including Myanmar. It can lead to “economic polarization,” where the most talented people will leave the country to take better opportunities and higher rewards in more advanced member countries. Therefore, there are initiatives to strengthen the CLMV countries in playing a more positive role in the AEC and to increase their prospects of benefiting from AEC participation (U Myint, 2011). However, such initiatives may not yet materialize to prevent the brain drain.

In 2012, the Myanmar government is trying to promote more foreign direct investment (FDI). It organized the “New Myanmar Investment Summit” in July 2012. Three hundred foreign companies were invited to attend the summit. A new foreign investment law is under amendment. Agriculture, oil and gas, mining, electric power and manufacturing are key economic sectors that the government wants investors to consider.

If we look at economic reform within Myanmar, the richness of local natural resources (natural gas, timber, precious stones and hydropower) can be an important platform for economic development, both for local consumption and exportation. Thailand has invested in the exploration and purchase of natural gas in Myanmar through the Thailand Petro-Chemical and Petroleum Company (TPP). The gas pipeline from Yadana links across the border through Kanchanaburi and reaches Rachaburi province in Western Thailand. As of 2011, mainland China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia are other Asian investors in Myanmar. Singapore has the highest number of companies there.

In addition, development in the agricultural sector according to the Myanmar Government Development Strategy in this field will increase the expansion of existing cash crops such as rice, maize, tapioca and beans. The Thailand Charoen Pokphand Group (CP) has an operation in contract farming for chickens and eggs in Myanmar. Economically, agricultural development and expansion directly affect land prices.

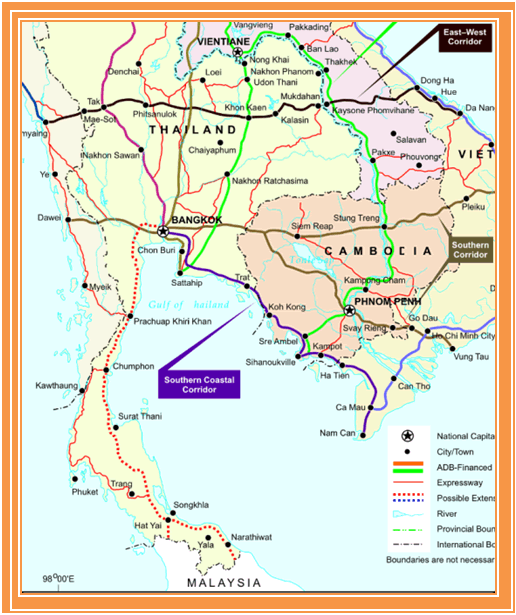

In the industrial sector, development can be seen in many new Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Thilawa (north of Yangon), Magway, Rakhine, Sagaing and Dawei (Min and Kudo, 2012). SEZs will attract more FDI into Myanmar, using existing natural resources and making more value-added. Although this is still in the near future, it reflects what kind of human resources are needed for such development. The construction of land links between Thailand and Myanmar, especially the Dawei-Phu Nam Ron Road link in Kanchanaburi province of Thailand, will play a vital role in transport and trade in mainland Southeast Asia because it will link the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean under the ADB East-West Economic Corridor plan.

If we look at economic reform within Myanmar, the richness of local natural resources (natural gas, timber, precious stones and hydropower) can be an important platform for economic development, both for local consumption and exportation. Thailand has invested in the exploration and purchase of natural gas in Myanmar through the Thailand Petro-Chemical and Petroleum Company (TPP). The gas pipeline from Yadana links across the border through Kanchanaburi and reaches Rachaburi province in Western Thailand. As of 2011, mainland China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia are other Asian investors in Myanmar. Singapore has the highest number of companies there.

In addition, development in the agricultural sector according to the Myanmar Government Development Strategy in this field will increase the expansion of existing cash crops such as rice, maize, tapioca and beans. The Thailand Charoen Pokphand Group (CP) has an operation in contract farming for chickens and eggs in Myanmar. Economically, agricultural development and expansion directly affect land prices.

In the industrial sector, development can be seen in many new Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Thilawa (north of Yangon), Magway, Rakhine, Sagaing and Dawei (Min and Kudo, 2012). SEZs will attract more FDI into Myanmar, using existing natural resources and making more value-added. Although this is still in the near future, it reflects what kind of human resources are needed for such development. The construction of land links between Thailand and Myanmar, especially the Dawei-Phu Nam Ron Road link in Kanchanaburi province of Thailand, will play a vital role in transport and trade in mainland Southeast Asia because it will link the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean under the ADB East-West Economic Corridor plan.

Conclusion: Implications of Migration to Myanmar Development

Given the economic reform in Myanmar, which will flourish within the next five years, the key question related to outbound labour migration to Thailand (and Malaysia and Singapore) will be whether migrant workers, both skilled and less skilled, will remain in destination countries or consider returning home. In the past, average incomes of families were inadequate to meet household consumption expenditures (household income and expenditure survey in 1997). Consequently, people escaped from Myanmar to find higher incomes in Thailand. Now that economic development is in progress and labour demands for economic, social and political development in Myanmar are obvious, migrant workers’ decision to return will depend on two major conditions: political stability and democratic freedom on one hand and economic opportunities on the other hand. The political condition is important because some professionals determined to stay and work in Thailand due to a lack of democratic reform in the past. Less-skilled workers were also affected by the authoritarian regime in the form of corruption, forced labour, forced relocation and armed conflict. Both groups will have a serious consideration to return when they are assured of political stability. Myanmar people are highly attached to their homeland and always want to go back.

Economic opportunities are manifested in job availability according to migrants’ occupational skills, fair wages and fair working conditions. A realistic professional said: “If the wage in Myanmar is not too different from here [Thailand], I don’t mind receiving a wage a little bit lower than what I receive now. But I expect an enabling working environment there.” As for less-skilled workers, daily wages in some SEZs like the Dawei Deep Seaport Project are up to Kyat 7,000 (equivalent to Baht 300 or US$10) as offered by the Italian-Thai Development Co. (ITD), while local subcontractors only offer Kyat 4,000. However, local informants indicated that not many migrant workers originating from Dawei will come back because they are well paid in Thailand and the cost of living in Myanmar is more expensive and increases by 35% for raw chicken. This is confirmed by the inflation rate fluctuation of between 57.1% and 1.5% during 2001-2009. In Dawei, workers who can speak Thai are hired by ITD. The tendency is that workers will compare wages and costs of living to ensure the balance of income. Then they will decide whether to return to Myanmar.

Among skills that migrant workers learned spontaneously while working in Thailand, construction, agriculture and some manufacturing skills are the most relevant to economic reform in Myanmar. However, those in the services and sales sector, including hotels and tourism, can also develop work skills that will be useful if they return home. The management aspect to match workers’ skills and human resources to current and future demands in Myanmar’s labour market will be the next challenge. Once employments are created, acceptable working conditions, including wages, will be the determining factors on returning. In this regard, an attempt to make income distribution among states and divisions more equal is important, as many migrant workers are ethnic minorities and people from poor divisions. In addition, fair wages can prevent local talented professionals from leaving the country to take higher rewards abroad.

Given the economic reform in Myanmar, which will flourish within the next five years, the key question related to outbound labour migration to Thailand (and Malaysia and Singapore) will be whether migrant workers, both skilled and less skilled, will remain in destination countries or consider returning home. In the past, average incomes of families were inadequate to meet household consumption expenditures (household income and expenditure survey in 1997). Consequently, people escaped from Myanmar to find higher incomes in Thailand. Now that economic development is in progress and labour demands for economic, social and political development in Myanmar are obvious, migrant workers’ decision to return will depend on two major conditions: political stability and democratic freedom on one hand and economic opportunities on the other hand. The political condition is important because some professionals determined to stay and work in Thailand due to a lack of democratic reform in the past. Less-skilled workers were also affected by the authoritarian regime in the form of corruption, forced labour, forced relocation and armed conflict. Both groups will have a serious consideration to return when they are assured of political stability. Myanmar people are highly attached to their homeland and always want to go back.

Economic opportunities are manifested in job availability according to migrants’ occupational skills, fair wages and fair working conditions. A realistic professional said: “If the wage in Myanmar is not too different from here [Thailand], I don’t mind receiving a wage a little bit lower than what I receive now. But I expect an enabling working environment there.” As for less-skilled workers, daily wages in some SEZs like the Dawei Deep Seaport Project are up to Kyat 7,000 (equivalent to Baht 300 or US$10) as offered by the Italian-Thai Development Co. (ITD), while local subcontractors only offer Kyat 4,000. However, local informants indicated that not many migrant workers originating from Dawei will come back because they are well paid in Thailand and the cost of living in Myanmar is more expensive and increases by 35% for raw chicken. This is confirmed by the inflation rate fluctuation of between 57.1% and 1.5% during 2001-2009. In Dawei, workers who can speak Thai are hired by ITD. The tendency is that workers will compare wages and costs of living to ensure the balance of income. Then they will decide whether to return to Myanmar.

Among skills that migrant workers learned spontaneously while working in Thailand, construction, agriculture and some manufacturing skills are the most relevant to economic reform in Myanmar. However, those in the services and sales sector, including hotels and tourism, can also develop work skills that will be useful if they return home. The management aspect to match workers’ skills and human resources to current and future demands in Myanmar’s labour market will be the next challenge. Once employments are created, acceptable working conditions, including wages, will be the determining factors on returning. In this regard, an attempt to make income distribution among states and divisions more equal is important, as many migrant workers are ethnic minorities and people from poor divisions. In addition, fair wages can prevent local talented professionals from leaving the country to take higher rewards abroad.

References

- ADB. 2012. Myanmar in Transition: Challenges and Opportunities . Asian Development Bank.

- BTI. Myanmar Country Report. Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index [Online]. 2012. Available from: http://www.bti-project.org .

- Chantavanich, S.with Premjai Vungsiriphisal and Samarn Laodumrongchai. 2007. Thailand Policies towards Migrant Workers from Myanmar . Bangkok: Asian Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies. Chulalongkorn University.

- Huguet, J. W. and Aphichat Chamratrithirong. 2012. Thailand Migration Report 2011 . Bangkok: International Organization for Migration.

- Ishida, M. (ed). 2012. Emerging Economic Corridors in the Mekong Region . Bangkok: Bangkok Research Center. IDE-JETRO.

- Min, Aung and Toshihiro Kudo. 2012 “Newly Emerging Industrial Development Nodes in Myanmar; Ports, Road, Industrial Zones along Economic Corridor” in Ishida (ed). Emerging Economic Corridors in the Mekong Region . Bangkok: Bangkok Research Center. IDE-JETRO.

- Myint, U. 2009. Myanmar Economy A Comparative View . Sweden: Institute for Security and Development Policy.

- Myint, U. 2011. Myanmar Economy: Challenges and Responses in years ahead . Power point presentation at Yangon Institute of Economies, 21 November 2011.

- Paitoonpong, S and Yongyuth Chalamwong. 2012. Managing International Labor Migration in ASEAN: A case of Thailand . Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute.

You can download this policy review at the IDE-JETRO website: http://www.ide.go.jp

Contact: Bangkok Research Center, JETRO Bangkok TEL:+66-2253-6441 FAX:+66-2254-1447