IDE Research Columns

Column

Group Discussion Can Complement Subsidies in Increasing the Demand for a Stigmatized Health Product

Rashesh SHRESTHA

Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia

June 2025

Psychological burdens stemming from social stigma can significantly influence individuals’ economic behavior, particularly in health-related decisions such as the adoption of effective health products. This creates a challenge for policymakers seeking to increase the uptake of such products to improve public health outcomes. Subsidies alone may be insufficient to drive adoption when stigma is involved. Drawing on insights from both economics and public health literature, this study investigates whether coupling subsidies with participation in a group discussion session can enhance demand for sanitary pads in Nepal—a product affected by menstrual stigma. The findings indicate that combining modest subsidies with group discussions offers a more cost-effective strategy for promoting stigmatized health products.

Influence of Stigma on Economic and Health Behavior

Psychological costs stemming from stigma can significantly influence economic behavior. In the health domain, traditional beliefs and taboos often discourage the use of beneficial health products and services. This phenomenon has been examined in contexts such as HIV testing and male circumcision (Young & Bendavid 2010). By reducing the (perceived) marginal benefit of health products, stigma poses a major barrier to their adoption, even when these products are well-known. This presents a challenge for policymakers attempting to increase the uptake of health technologies to build health capital, which is crucial for poverty alleviation and economic growth.

Menstruation is one domain where stigma has a profound impact. In many societies, deeply entrenched norms label menstruating females as “unclean,” creating social stigma. This menstrual stigma imposes psychological costs (e.g., shame and fear of social exclusion) that deter females from using sanitary pads despite awareness of their benefits. This “product stigma” also limits information-seeking behavior, as females often avoid discussing menstruation with peers. Even when informed, embarrassment discourages public purchases, leading individuals to undervalue the benefits of these products. Research has shown that inadequate menstrual health management negatively affects girls’ and females’ human capital development and productivity (Ichino & Moretti 2009). A combination of high product costs, budgetary constraints, and cultural taboos contributes to poor menstrual health practices (Sommer et al. 2015).

Increasing Adoption of Stigmatized Health Products with Group Discussion

Subsidies alone may not be sufficient to increase the adoption of stigmatized products. For non-stigmatized goods, subsidies lower the final price and thus stimulate demand. Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in developing countries have demonstrated the effectiveness of subsidies in promoting health product use (Ashraf et al. 2010; Meredith et al. 2013; Dupas 2014). However, for stigmatized products, psychological costs—conceptualized as negative utility in economic models—introduce an additional barrier, thereby reducing the impact of subsidies alone.

Building on public health research suggesting that group discussions and peer information sharing can reduce stigma in areas such as HIV, mental health, and menstruation (e.g., Creel et al. 2011; Henderson et al. 2017; Bobel et al. 2020), we conducted an RCT in Nepal to assess whether combining subsidies with group discussions could increase the uptake of sanitary pads. We hypothesized that reducing the psychological costs associated with stigma through group discussions would make females more responsive to price reductions and thus more likely to purchase sanitary pads. The study was designed to compare purchasing decisions between females who participated in a group discussion and those who did not.

The study was implemented in five villages in Nepal with participants aged 15–50. A baseline survey collected information on demographics, socioeconomic status, and menstrual health knowledge and practices. Households were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: subsidy-only and subsidy-plus-discussion. The experimental design featured 10 distinct treatment groups, based on five levels of subsidy within each main group. In total, 707 observations were collected, with some excluded due to missing data.

Within each group, participants received discount coupons for sanitary pads, with subsidy levels randomly assigned at 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, or 90%. Females in the subsidy-only group received coupons at home, while those in the subsidy-plus-discussion group received theirs at the end of a facilitated group session. A pack of six sanitary pads cost Rs. 70 (approximately $0.62), and females typically used three to four packs per cycle—representing a substantial expense for low-income households. Coupons were redeemable within 45 days at one of two designated local pharmacies, which were reimbursed in advance and maintained detailed transaction records.

Led by health professionals, the group discussion sessions covered female health, menstrual hygiene, and related social beliefs, specifically addressing stigma around menstruation. These sessions aimed to normalize conversation and create a supportive environment. They also highlighted the negative consequences of menstrual stigma and referenced the 2017 criminalization of Chhaupadi (i.e., isolating menstruating females). The discussions were not intended to promote sanitary pads, as 85% of participants were already aware of them at baseline. Rather, the primary aim was to reduce the psychological barriers associated with using stigmatized health products.

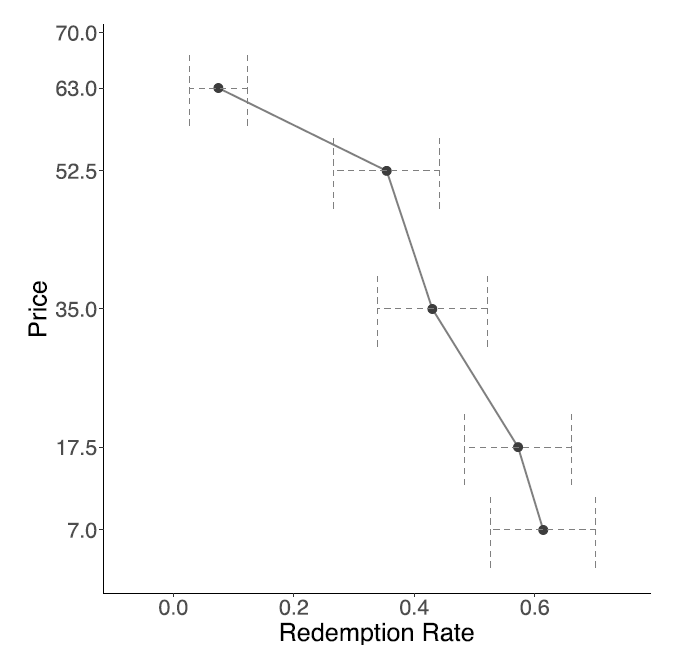

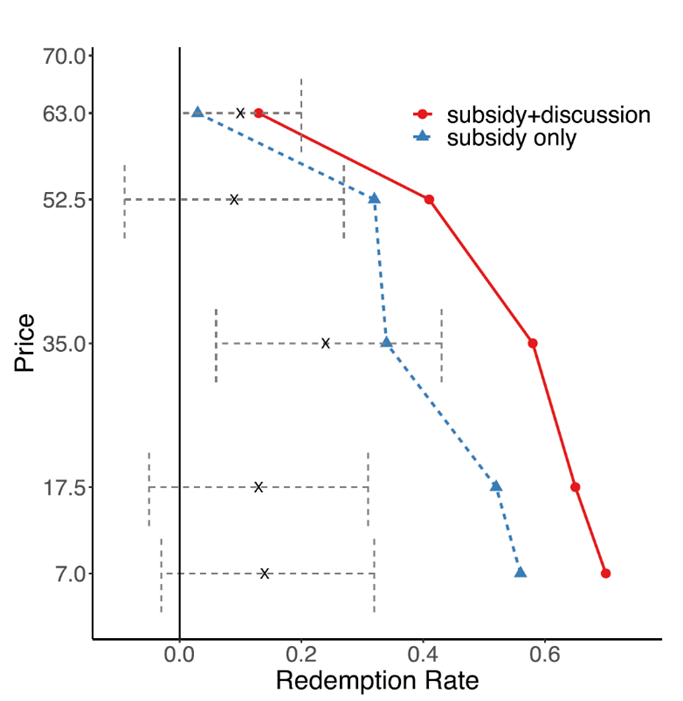

We analyzed coupon redemption data to assess purchase behavior. Results showed that higher subsidy levels increased product uptake in both groups; however, females who participated in group discussions exhibited significantly higher demand for sanitary pads compared to those who received only the coupon. This pattern is illustrated in Fig. 1. The left panel shows that redemption rates increased as the effective price decreased due to higher subsidies. The right panel compares demand between the two treatment groups, revealing consistently higher redemption rates among participants in group discussions at every price level. That is, group discussion enhanced demand for sanitary pads. Further analysis showed that the discussion had the strongest impact on females with higher psychological burdens—those who had been confined to sheds, labeled “untouchable,” or had never previously purchased pads—suggesting the intervention effectively reduced stigma. These results were robust to selection bias arising from non-compliance.

(a) Pooled

(b) by treatment groups

Figure 1. Demand Curve for Sanitary Pads

Source: Shrestha and Shrestha (2023).

Policy Implications

Efforts to increase the adoption of menstrual health products have traditionally focused on free or subsidized distribution. However, our findings indicate that pairing group discussions with subsidies is more effective than relying on subsidies alone to promote the use of health products affected by stigma. This study highlights the critical role of psychological costs in shaping health-related decisions and the need to address these costs when designing public health interventions. Although transforming deep-rooted societal stigma may require long-term efforts, targeted approaches such as group discussions can meaningfully reduce the psychological barriers to adoption, thereby increasing the use of essential products like sanitary pads.

Author's Note

Rashesh SHRESTHA is an economist at the Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA). This column is based on the 2023 article, Shrestha, V., and R.Shrestha. 2023. “The Combined Role of Subsidy and Discussion Intervention in the Demand for a Stigmatized Product.” The World Bank Economic Review 37(4): 675-705. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhad023

References

Ashraf, N., J. Berry, and J. M. Shapiro. 2010. “Can Higher Prices Stimulate Product Use? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Zambia.” American Economic Review 100(5): 2383-2413. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.5.2383

Bobel, C., I. T. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling, and T. A. Roberts. 2020. The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Singapore: Palgrave McMillan.

Creel, A.H., R. N. Rimal, G. Mkandawire, K. Böse, and J. W. Brown. 2011. “Effects of a Mass Media Intervention on HIV-related Stigma: ‘Radio Diaries’ Program in Malawi.” Health Education Research 26(3): 456-465. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr012

Dupas, P. 2014. “Getting Essential Health Products to Their End Users: Subsidize, but How Much?” Science 345(6202): 1279-1281. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1256973

Henderson, C., E. Robinson, S. Evans-Lacko, and G. Thornicroft. 2017. “Relationships between Anti-stigma Programme Awareness, Disclosure Comfort and Intended Help-seeking Regarding a Mental Health Problem.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 211(5): 316-322. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.195867

Ichino, A., and E. Moretti. 2009. “Biological Gender Differences, Absenteeism, and the Earnings Gap.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(1): 183-218. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.1.1.183

Meredith, J., J. Robinson, S. Walker, and B. Wydick. 2013. “Keeping the Doctor away: Experimental Evidence on Investment in Preventative Health Products.” Journal of Development Economics 105: 196-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.08.003

Shrestha, V., and R. Shrestha. 2023. “The Combined Role of Subsidy and Discussion Intervention in the Demand for a Stigmatized Product.” The World Bank Economic Review 37(4): 675-705. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhad023

Sommer, M., J. S. Hirsch, C. Nathanson, and R. G. Parker. 2015. “Comfortably, Safely, and without Shame: Defining Menstrual Hygiene Management as a Public Health Issue.” American Journal of Public Health 105(7): 1302-1311. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525

Young, S. D., and E. Bendavid. 2010. “The Relationship between HIV Testing, Stigma, and Health Service Usage.” AIDS Care 22(3): 373-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120903193666

* The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

**Thumbnail image: Sanitary pads ©ShotShare

This column is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed