IDE Research Columns

Column

Upskilling Vietnam’s Private Firms and Labor Force Needs Capital Market Reforms

Diep PHAN and Ian COXHEAD

School of Business, Beloit College, USA; Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

April 2025

We explore differences in demand for skilled workers by private and state-owned enterprises in Vietnam, an economy in transition to market-driven growth. State-owned firms in Vietnam have privileged access to financial capital and face lower borrowing costs. Because of this, they choose technologies that are capital-intensive and demand more skilled labor, a complementary input, while private firms rely on low-technology methods and less-skilled labor. Because the private sector is by far the larger employer, a more level capital market playing field would likely raise aggregate demand for skills. Higher skills demand should in turn improve incentives to invest in education.

Capital, Labor and Growth in Vietnam

Vietnam has experienced rapid economic growth since the 1990s, when it began the policy transition from command to market economy. However, the pace of reform has been slow in domestic financial markets and in the state-dominated system of enterprise ownership, resulting in a persistently unequal playing field between private and state firms. With easy and cheap access to credit, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) tend to be larger and more intensive in the use of technology, capital and skilled labor, while also being less efficient than private firms, which are mainly small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Meanwhile, the country’s labor market exhibits signs of underinvestment in skills. Enrolments and scholastic achievement in compulsory grades are high, but rates of secondary completion, progression to tertiary, and tertiary completion have all lagged (Dang and Glewwe 2018; Parajuli et al. 2020; Banh et al. 2024). The skill premium, a measure of expected gross returns to education, remains influential in school-to-work transitions other than in the most wealthy households (Coxhead et al. 2022). Paradoxically, however, in Vietnam the skill premium remains low by international standards, and even declined for most of the decade following WTO accession in 2007 (Doan and Gibson 2012; McGuinness et al. 2021). Other studies examining this puzzle find that the declining skill premium cannot be explained by an increase in the supply of more-educated workers, nor by a decline in the quality of education (Banh et al. 2024).

Capital Markets and Demand for Skilled Workers: Analysis

Technology, skills and capital are complementary inputs in production, so what does unequal access to capital mean for growth of aggregate skills demand? Using data from Vietnam’s Enterprise Census, we find that capital access has a strong influence on choice of production methods. Firms with limited access to financial markets are less able to expand production, and are also less likely to adopt modern methods. Both of these constraints stunt the growth of demand for skilled workers.

Vietnam’s SOEs and trading companies have been relatively well insulated from economic policy reforms. Even after three decades of movement toward a market-driven economy, only about 10% of state-owned capital has been privatized (Phan Le 2022). SOEs and similar enterprises retain privileged access to domestic credit from the state-owned banking system. State banks, in turn, engage heavily in “policy lending,” or the systematic favoring of SOEs in domestic credit allocation, thereby crowding out SME borrowing. Preferential treatment for SOEs has been estimated to contribute 81% of capital misallocation and 38% loss in aggregate manufacturing productivity (Phan Le 2022).

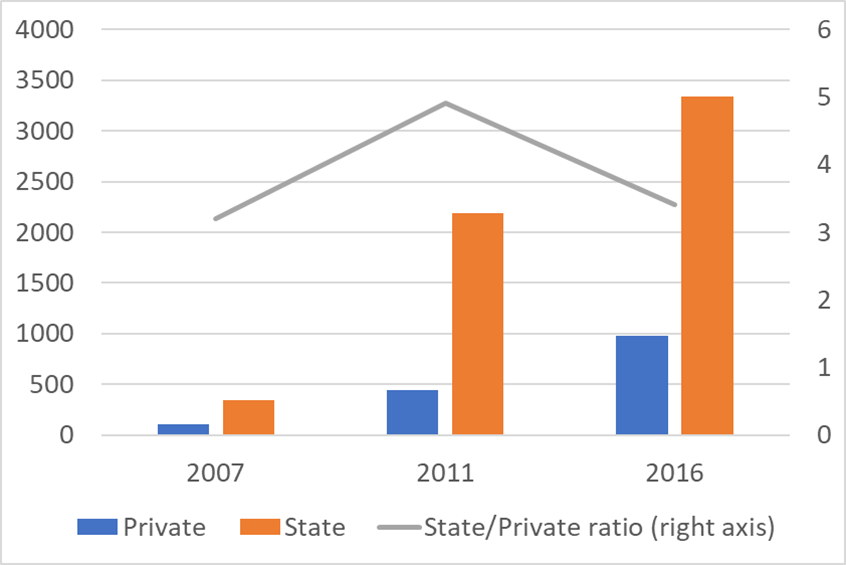

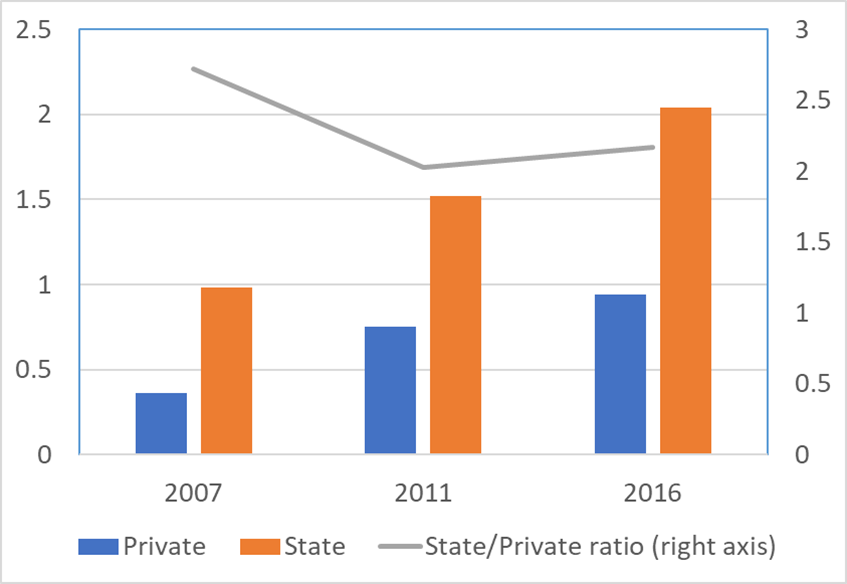

In modeling work we focus on within-industry choice of technology and capital intensity by firms under either state or private ownership. The choice between low-tech, labor-intensive production methods and capital-intensive, skill-intensive methods involves up-front investment costs. The skill-intensive choice is thus more profitable for firms with longer expected production runs and for firms with lower financing costs. State firms, facing lower borrowing costs, will tend to choose the high-efficiency, high-fixed cost technology, while private firms will choose the low-efficiency, low fixed-cost technology, other things equal. These choices then drive differences in their demand for skilled labor. We then test these predictions against data. Private firms (which make up 94% of all firms) are much smaller in terms of both revenue and employment, and employ significantly less fixed capital per worker (Figure 1). The percentage of state firms self-reporting as credit-constrained is 5.7%, while for private firms it is 12.6%. Over 58% of state firms have loans, but only 33% of private firms. Finally, private firms also employ fewer skilled workers for each unskilled worker (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Fixed Capital per Worker (VND’000)

Figure 2: Skilled Workers per Unskilled Worker

Source: Authors’ calculations from the Vietnam Enterprise Census.

In further statistical estimates we find that after controlling for differences due to region and industry the average state firm has a fixed capital stock roughly three times larger than that of an average private firm. Even among the 10% of biggest firms by revenue, this ratio remains large at 1.65. These differences are replicated in skilled labor usage: the average state firm has a skilled-unskilled labor ratio 1.32 times higher than that of the average private firm, after controlling for regional and industry differences. These and other estimation results also confirm that smaller firms (nearly all of which are private) are largely limited to labor-intensive techniques. They increase output not by upgrading capital inputs and technology, but by adding unskilled labor. Large firms, by contrast, are more likely to reach a scale at which it becomes profitable to adopt more capital-intensive, skill-intensive technologies. But because most employment is in smaller firms, the less skill-intensive effect is likely dominant.

The IMF and many other agencies have recommended that Vietnam weaken or eliminate policies and practices that favor state enterprises. Other things equal, relaxation of capital market policies that favor state firms would increase their borrowing costs, and if this reduces crowding-out, may also lower capital costs for private firms. Our model then shows several possible scenarios, among which the most interesting one is that if there are many private firms close to the threshold of new technology adoption, then better capital market access could induce a significant private sector movement towards high-efficiency technologies and an accompanying increase in demand for skilled workers. Our model indicates that such a transition, if it were to occur, could be a game-changer for economic growth since it would signal a rise in aggregate demand for skills, likely pushing up the skill premium. Together, the technology shift and increase in skills demand have the potential to accelerate industrial transition and sustain Vietnam’s progress through middle-income.

With better data, the study could provide more detailed guidance. First, we don’t know how many private-sector firms may exist in the adoption threshold region, nor what complementary policies might be necessary to induce a large-scale shift. Second, higher capital costs for SOEs will tend to reduce their demand for skilled labor. which in turn will put downward pressure on the skill premium. Since the great majority of employment is in private firms, however, their responses would likely dominate the effects of any SOE contraction. Finally, if the Vietnamese government were to implement a package of policies bundling capital market reforms together with other measures, the skills demand effect of SOE shrinkage could in principle be more than offset by increased demand due to efficiency gains elsewhere. Some such policies were outlined in the 2107 Law on Small and Medium Enterprises. Exploring their implementation and impact is an area for future research.

Raising Skills Demand Could Also Increase Their Supply

Vietnam, like many middle-income economies, faces the long-run challenge of reducing its reliance on labor-intensive, low-tech production and promoting more skill-intensive methods. One condition for success is that it also transform its labor force, keeping adolescents and young adults in school longer to ensure that they enter the labor force with more advanced training and capabilities. Students’ perception of the benefits of additional education depend, in part, on perceived returns to skills acquired through schooling as compared with early entry to the blue-collar labor force. Returns to skills rise with labor productivity, which is itself increasing in the use of complementary inputs such as capital and technology. Our research using enterprise-level data shows that persistent capital market distortions inhibit growth in demand for skills by favoring a small subset of industries at the expense of a much larger private sector in which capital constraints limit skilled labor demand.

About the Authors

Diep Phan is Professor of Economics at Beloit College, USA. Ian Coxhead is Senior Research Fellow at IDE-JETRO. This column is based on their 2024 article, “Capital Market Distortions and Skills Demand in a Transitional Economy: The Case of Vietnam.” Economics of Transition and Institutional Change: 1-23, accessible at https://doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12444.

References

Banh, T. H., T. H. Dao, P. Glewwe, and G. Thai. 2024. “An Investigation of the Decline in the Returns to Higher Education in Vietnam.” Education Economics 32: 665-685.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2024.2362262

Coxhead, Ian, N. D. T. Vuong, and P. Nguyen. 2022. “Getting to Grade 10 in Vietnam: Does an Employment Boom Discourage Schooling?” Education Economics 31(3): 353–375.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2022.2068138

Dang, H.-A.H., and P. W. Glewwe. 2018. “Well Begun, but Aiming Higher: A Review of Vietnam’s Education Trends in the Past 20 Years and Emerging Challenges.” Journal of Development Studies 54(7): 1171–95.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1380797

Doan, Tinh, and John Gibson. 2012. “Returns to Education in Vietnam during Recent Transformation.” International Journal of Economics and Education 3(4): 314-329.

McGuinness, Seamus, Elish Kelly, Phuong Pham, and Adele Whelan. 2021. “Returns to Education in Vietnam: A Changing Landscape.” World Development 138(3).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105205

Parajuli et al. 2020. Improving the Performance of Higher Education in Vietnam: Strategic Priorities and Policy Options. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/347431588175259657/pdf/Improving-the-Performance-of-Higher-Education-in-Vietnam-Strategic-Priorities-and-Policy-Options.pdf

Phan, Le. 2022. “Capital Misallocation and State Ownership Policy in Vietnam.” The Economic Record 98(S1): 52-64.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12666

* Thumbnail image: A man working with a sawmill in a village near Hanoi, Vietnam. Photo taken by the author.

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

©2025 Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO)

This column is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed