IDE Research Columns

Column

Back to Square One: Exploring Re-emigration Intentions and Preferred Destinations Among Nurse Returnees in India

Yuko TSUJITA

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

September 2024

International migration patterns are becoming increasingly diverse and complex, with some migrants moving across multiple borders throughout their lives, while returning migrants may only return home temporarily. This study examines the likelihood of future migration and explores migration trajectories of Indian nurses returning from Arabian Gulf countries. The analysis reveals that nurses who return to India are more inclined to emigrate again if they are currently employed in the private sector, which offers lower financial rewards compared to the public sector in India. Conversely, nurses are more likely to settle permanently in India if they can secure higher pay and permanent contracts. Ensuring decent pay and better working conditions for nurses in countries that often lose them through emigration is critical to retaining these healthcare professionals.

Nurses Moving Across Borders

Nurses are essential in health care, including preventive medicine. It is increasingly apparent that nurses in many communities, hospitals, and aged-care facilities were born and trained abroad. Globally, one in every eight nurses works in a country other than where they were born or trained.1 The global shortage of nurses pushes them to move across borders, and they often make multiple moves throughout their lives as the global competition for their services intensifies. Some move back and forth between two or more countries, while others may first work in one foreign country and then move on to other countries that offer better work and life conditions until they reach their preferred destination. In the process of multiple moves across borders, nurses might return to their country of origin. When they do, are they still willing to go abroad again, and if so, what countries are their likely next destinations?

Migration to the Gulf Cooperation Countries

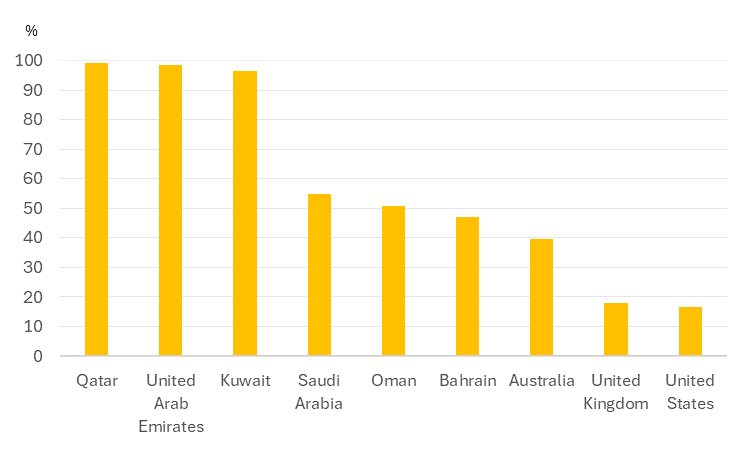

While international migration to developed countries is often associated with the prospect of permanent settlement in those destination countries, the probability of return migration is higher when it is difficult for foreigners to obtain a long-term visa and/or citizenship in the destination country. An example of this is the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, which comprise Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Temporariness and circularity are inherent in the migration system of the GCC, which largely depends on foreigners for its health care workforce. These countries promote the nationalization of their workforces, preferring to replace foreign workers with their own citizens; however, the extent of nationalization among nurses varies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of Foreign-Born Nursing Personnel (latest available data)

Note: The UK’s figure refers to foreign-trained nurses.

Source: World Health Organization, National Health Workforce Accounts Data Portal

(https://apps.who.int/nhwaportal/); UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention (2021).

Who Would Like to Emigrate Again, and Where?

India is one of the major “nurse exporting” countries, with an estimated 57% of its overseas nurses working in GCC countries.2 In 2020-21, we conducted a survey with 200 Malayalam-speaking nurses who had returned from GCC countries and were working in nurse-related occupations in India. As a complete list of registered nurses who had returned from GCC countries was not available, we used snowball sampling in which respondents introduced us to their colleagues and friends. It is worth mentioning that finding a substantial number of nurses who have returned from the West was not easy. A little more than half of the nurses in our sample who had returned from GCC countries expressed their desire to emigrate again. As a next destination, these nurses tended to prefer destinations in Western countries over GCC countries. Only a minority of nurses who have worked for only one GCC employer expressed their interest in repeat migration to the GCC region. While circularity is a characteristic of migration to GCC countries, it may not be as common among nurses.

The most significant factor affecting the willingness to go abroad is the current workplace in India. Nurses currently working in India’s private hospitals are more willing to go abroad than their counterparts who work in a public hospital. Furthermore, fixed-term contract nurses in public hospitals are more willing to go abroad again than their counterparts who are permanent staff nurses in public hospitals, although their willingness is not as high as those working in private hospitals. In particular, those willing to go abroad would like to go to Western countries but not to GCC countries, as the former typically often offer higher remuneration, better working conditions, increased opportunities to obtain citizenship, and other favorable work and lifestyle conditions. Our in-depth interviews with nurses reveal that GCC countries are often seen as easier and more affordable to access than Western countries and are considered as a steppingstone to working in Western countries.

Domestic Nurse Labor Market

Why are nurses in the private sector more willing to go abroad? Private hospitals in India offer much lower basic pay and inferior working conditions compared to public hospitals.3 While public hospitals are an attractive option, aspiring nurses have to pass a competitive civil service examination to work there. Moreover, in recent years, the number of fixed-term contract nurses in public hospitals and health centers, who receive lower wages and work in poorer conditions compared to permanently employed nurses, has increased in many states of India, mainly due to fiscal constraints. Increased hiring of fixed-term contract nurses to address the nursing shortage has been particularly evident since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding the types of workplace nurses leave when departing from India and the ones they select immediately upon returning to India in each instance of circular migration, some nurses in our sample left the private sector, or contract-based jobs in the public sector, when they emigrated, and took permanent jobs in the public sector upon their return, but not vice versa. One of the major reasons for returning to India is securing a government job. Nurses generally prefer working in the public sector in India to working in GCC countries.

Policy Implications

The global demand for nurses is expected to increase further, especially in developed countries, due to aging populations, shortages of local nurses, nurse turnover, and the transition from family-based home care to institutional care, among other factors. The present study indicates that nurses are likely to settle permanently in India as long as they secure higher pay and permanent contracts (Tsujita, Oda, and Rajan 2023).

The return migration of nurses holds significant importance, especially in the context of the recent increased global demand for health care workers. Nurse returnees, who have acquired knowledge and skills during their time working abroad, are expected to make valuable contributions to the health care sector in the countries of their origin, particularly in developing countries where the per capita number of nurses is significantly lower than in developed countries.

Although remittances play a vital role in supporting families back home and contributing to the economy in their home countries, the outflow of nurses has not resulted in higher wage levels in India. In particular, the salaries and working conditions for nurses in private hospitals have not significantly improved. Following a Supreme Court order, many states have set minimum wage standards for nurses working in private hospitals. However, these standards are not necessarily enforced and nurses continue to struggle to receive even the minimum wage.

Unless hospitals guarantee decent pay and better working conditions across the board, Indian nurses, particularly those in private hospitals, may continue to migrate abroad and the country will remain the primary source of the global nursing workforce, suffer from a shortage of nurses, and face a “brain drain” in India’s the nursing profession.

Author’s Note:

This column is based on: Tsujita, Yuko, Hisaya Oda, and S. Irudaya Rajan. 2023. “Intention to Emigrate Again and Destination Preference: A Study of Indian Nurses Returning from Gulf Cooperation Council Countries.” Migration and Development 12 (1):91-110. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/21632324231194766

Notes:

- WHO (2024).

- WHO (2017).

- For instance, according to a nurse union leader in May 2019 in Kerala, the starting monthly salaries, including various allowances, in central and state governments were approximately INR 68,000 and INR 32,000, respectively. In private hospitals, newly graduate nurses earned an average of INR 5,000 to INR 6,000 per month.

References

Ministry of Health and Prevention. 2021. Number of Health Service Employees by Sector 2019, The United Arab Emirates. (Accessed on 22 August 2022)

World Health Organization. 2017. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain: Migration of Nursing and Midwifery Workforce in the State of Kerala, India Country Case Study Kerala. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/2017-healthworker-migration-kerala

World Health Organization. 2024. Nursing and Midwifery. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery

* Thumbnail image: COVID-19 Nurse (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COVID-19_Nurse.jpg) (Sara Eshleman via Wikimedia Commons)

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.