IDE Research Columns

Column

Who Are Professional Judges in China? Understanding the “Rule of Law” under the Chinese Communist Party

Hiroko NAITO

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

February 2024

Xi Jinping’s administration strongly encourages judges to be professionalized under the political slogan of the “rule of law.” Thus, the question arises, are judges in China professionalized in the context of political science? Naito (2020) argues that the aim of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as the CCP is the most highly-educated organization with a meritocratic political system, behind professionalization is the unification of the judges’ quality and their integration with the CCP. However, despite the CCP's promotion of legal professionalization, this study revealed that judges and the local people's court controversially maintained conservative behavior. More precisely, they prefer to maintain the status quo, whereas the CCP's policy and the law attempt to change the interest structure in which they participate.

What Type of Judges Exist in China?

How does a regular person imagine judges? Someone imagines a person who is serious, cloistered, and does not smile. Others picture a friendly, social, and intelligent person. Those opposite images demonstrate the main stereotype of a judge in Japan and the United States. According to a famous anecdote, a Japanese judge is prohibited from joining bird-watching activities because they may have a private connection with the participants. Controversially, a judge in the U.S. is usually encouraged to participate in social activities, such as a basketball team, to share common sense with society (Foote 2007).

The image of judges differs considerably in Japan and the U.S., and even more in China. Although the national bar examination began in 2002 in China, not all judges are legally qualified.1 Many judges perceive themselves as government officers rather than professional legal staff, usually those transferred from other administrative organs or veterans. Thus, the issue of how to professionalize judges to ensure fair judgments in court has become a central issue in discussing the “rule of law” in China.

Why Professionalized Judges Matter?

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China stipulates that “the People’s Court shall, in accordance with the law, exercise judicial power independently and is not subject to interference by administrative organs, public organizations, or individuals.” This implies that the People’s Court can work independently. However, is it true?

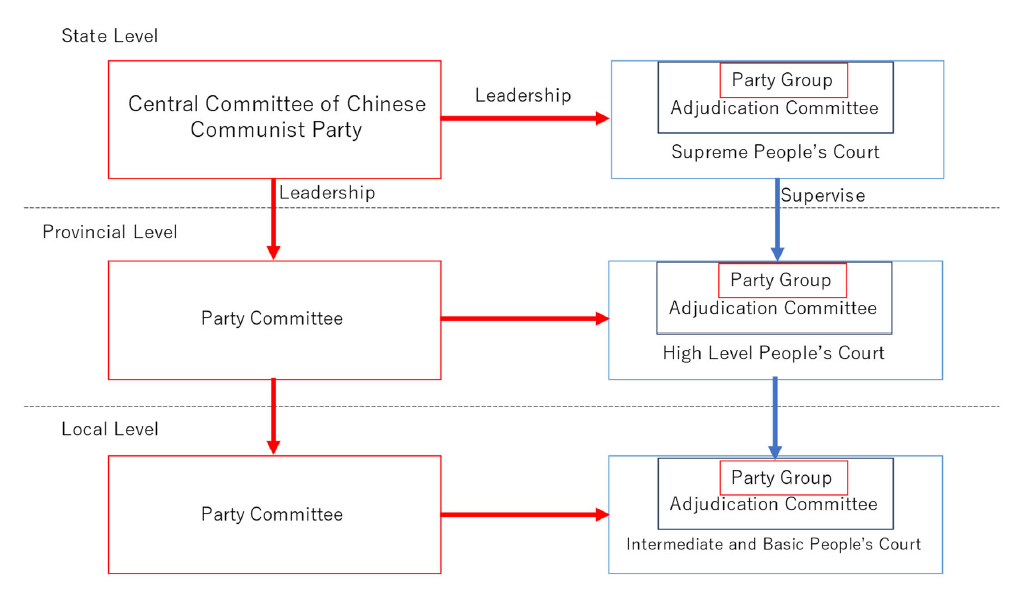

The answer is no. The CCP retains strong leadership over the People’s Court in two ways. First, the People’s Court establishes adjudication committees at all levels and performs its duties by discussing the decision to apply the law in significant, complex, and complicated cases. Based on this rule, the adjudication committees can make essential decisions. The members of its committees mostly overlap with the party members in the People’s Court. The judges can only make a judgment with the authority of the adjudication committees, which are equivalent to party committees.

Second, at the same administrative level, the party committee has substantial personnel authority over the judges. Although the judicial reform under Xi Jinping’s administration has increased the power that the local party committee substantially has to appoint judges to the provincial level, the authority of the party committees at the same administrative level is still strong in many provinces (Wang 2021).

Figure 1. Relationship between the Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Court

Source: Author.

Professionalizing the judges may transform the power structure between the CCP and the People’s Court. Judges may independently render a decision based on their legal expertise, even if it conflicts with the conclusion of the adjudication committee. Ginsburg and Moustafa (2008) argue that the principal-agent relationship between the CCP and the government would develop a conflict as the government becomes professionalized. Their findings support discussions of the relationship between the CCP and the People’s Court. Thus, Naito (2020) examined how the professionalization of judges affected the CCP’s authority over the People’s Court and ’judges’ behavior.

Two Attempts for the Professionalization of Judges in China

If the professionalization of judges can create an agency gap, why does the CCP aim to encourage it?

Historically, the first attempt to professionalize the judges was to support international trade and economic growth. After the Cultural Revolution, which crashed the judicial system, the CCP immediately rebuilt it and proposed the “Open and Reform” policy in the late 1970s. To create a legal profession after the end of the Cultural Revolution implied switching from being a veteran to a judge. When the economy began to grow rapidly in the 1980s, the function of the People’s Court gradually received attention to resolve the increased social conflict, domestically and internationally. The 13th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 1987 discussed enhancing professional legal skills while the judges keep their political talent. Since then, the CCP has set up and revised the Judges Law to upgrade the requirements for the judges to include political behavior in addition to legal knowledge.

The second attempt was to deal with regional protectionism, namely, the behavior to protect or give preference to the region’s economic and political interests by regional courts. The People’s Court prioritizes the will of the party committee when it declares the judgment because the local party committee has a firm authority over the local people’s court through the power to appoint and promote judges. Usually, the Central Government and the CCP respect the authority relationship between the Party Committee and the People’s Court at the local level to maintain the regime; however, it is not supported if they prioritize the regional benefit rather than the requirement of the Central Government or the rule that law defines. Therefore, the CCP aims to eliminate regional protectionism and unify the judgments by professionalizing them.

Human Warmth (人情: renqing) in the People’s Court

Based on data on the educational background of lawyers, approximately 30% of judges do not have a high education and are nonprofessional. The judges in the People’s Court represent a mixture of both old and new-generation judges. A judge from the old generation at the Higher People’s Court at a provincial level in a coastal district stated, “Recently, many judges in the new generation take responsibility for cases. Rejuvenation of the People’s Court happens rapidly.” Does the conflict between the old and new generations occur as the new generation judges with unified legal knowledge are promoted?

According to my interviews with judges, this does not (Naito 2020). One judge of the new generation stated, “the judges in the old generation cooperate with us; the relationship with them is good.” They recognize that “the new generation has a high-level knowledge of legal theory. Contrarily, the old generation has rich experiences and is good at dealing with cases with human warmth.” Furthermore, “the new generation gets the same level of education that Western countries promote; however, their education as “legal supremacy” is too ideal. After we start working at the People’s Court and experience a real case, they notice how much people prefer a judgment with human warmth.” In addition, they pointed out that “according to this circumstance, the new generation respects the old generation, because they can figure out the cases with human warmth. The new generation believes they should learn how the old generation performs.”

A preference for settlement by discussion over judgment based on the written law remains rooted in the court culture in China. Thus, learning a culture that is deeply ingrained in the People’s Court is indispensable for performing as a “good” judge in court. The new-generation judges are self-censored, and they are incapable of giving honest opinions and evaluations about the old generation because the latter has a superior position. The old generation would be able to manage the promotion of the new generation, which makes it necessary for the new generation to learn the old generation’s way of handling cases.

Final Remarks

The acceleration of the professionalization of the judges has induced a relatively more conservative behavior of the People’s Court and the judges. One reason is that the old generation of judges is still superior to the new generation in status and mediation skills. Another reason is regional differences due to the country size. The CCP has radically and uniformly promoted the professionalization of judges to such an extent that a judge in the People’s Court in the poor inland region confessed to the local newspaper that he was forced to falsify data because he could not meet the demands for reform.

Let us go back to the puzzle at the beginning. Are judges professionalized in China in the context of political science? This column explains that the CCP’s motive for professionalizing judges was the unification of the judge’s quality and their integration with the CCP to accelerate economic growth and eliminate regional protectionism. However, the judges have aimed to keep the status quo and relatively exhibited their conservative behavior.

Author’s Note

This column is based on the following research:

Naito, Hiroko. 2020. “‘Rule of Law’ under the Chinese Communist Party’s Leadership: The Case of the Professionalization of Judges and the CCP’s Governance of the People’s Court.” In State Capacity Building in Contemporary China, edited by Hiroko Naito and Vida Macikenaite, 66–92. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8898-9_5

Note:

- Unfortunately, the number of qualified/nonqualified judges is unclear. Naito (2020) defines the unqualified judges as an “old generation.”

References

Ginsburg, Tom, and Tamir Moustafa, eds. 2008. Rule by Law: The Politics of Courts in Authoritarian Regimes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wang, Yueduan. 2021. “‘Detaching’ Courts from Local Politics? Assessing the Judicial Centralization Reforms in China.” China Quarterly 246: 545–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741020000740

Foote, Daniel H. 2007. Nameless Faceless Justice: Will Japan’s Courts Change. 名もない顔もない司法: 日本の裁判は変わるのか [in Japanese], trans. Masayuki Tamaruya. Tokyo: NTT Shuppan.

Other Works by This Author

Naito, Hiroko. 2017. “The Political Role of the People’s Court and Authoritarian Regime Resilience: The Revision of the Environmental Protection Law in China.” Issues and Studies 53(4) December: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1013251117500126

Naito, Hiroko. 2021. “The Logic of the Chinese Communist Party’s Administrative Procedure Law: Controlling Regime Insiders and the “Democratic” Function of the People’s Court” [in Japanese]. Asian Studies 67 (3): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.11479/asianstudies.67.3_1

* The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

** Thumbnail image: Court photo in China (taken by the Author).