IDE Research Columns

Column

Can Attitudes toward Job and Workplace Influence Turnover Intentions among Migrant Workers? Evidence from a Survey of Employees in China

Hisatoshi HOKEN

Kwansei Gakuin University

August 2024

With the gradual decline in the country’s working-age population and the rapid increase in the wage levels for its blue-collar workers, it is increasingly important for manufacturers in China to improve human resource management for migrant workers to enhance their embeddedness and commitment to the workplace and reduce turnover. To examine migrant workers’ attitudes toward their jobs, we conducted a survey of factory employees in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Our results show that job embeddedness significantly enhances these employees’ organizational commitment to their workplaces, and that greater organizational commitment significantly reduces turnover intentions. Meanwhile, when migrant workers are divided into two age groups (younger than 25 years and 25 years or older), we find that job embeddedness has significant positive effects on organizational commitment for only the younger group.

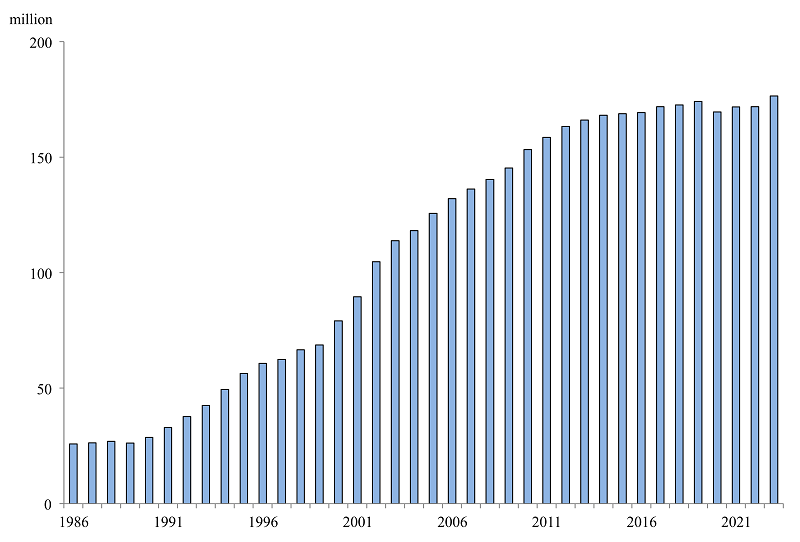

Migrant Workers and World Factory

Cheap labor has been one of the most important factors in the rapid growth of China’s manufacturing industry, and huge numbers of workers have migrated from the country’s poor, rural, inland areas to its relatively developed coastal areas. The total numbers of estimated migrant workers each year from 1986 to 2023 are summarized in Figure 1. As shown in the figure, the number remained fairly steady in the late 1980s at around 30 million people, as many farmers remained in rural areas and engaged in farming. In the 1990s the number of migrant workers began to increase gradually, especially after Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour, and grew considerably during the 2000s, reaching approximately 150 million in 2010. Manufacturers in China employ these unskilled laborers at low wages to increase their production volumes; thus China became the “world’s factory” by producing large quantities of a wide variety of products.

Figure 1. Total Number of Migrant Workers in China

Source: Compiled from National Rural Social-economic Survey Data Collection, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey, and Monitoring Survey Report of Migrant Peasant Workers in China.

However, as the working-age population in rural areas gradually declined, the supply of migrant worker began to stagnate in the early 2010s. A shortage of migrant workers and a preference for nonphysical labor among urban and rural populations led to increases in the wages of blue-collar workers. Moreover, the generation gap between younger and older migrants has grown considerably since roughly the late 2000s. Compared with older migrant workers, younger migrants tend to have higher expectation for their jobs and urban life, and have a greater awareness of their legal and socioeconomic rights (Cheng et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2018). This generation gap complicates personnel management in the workplace, resulting in more frequent turnover among migrant workers.

Organizational Commitment and Job Embeddedness of Migrant Workers

Consequently, major manufacturing companies in China have begun to recognize that migrant workers are no longer cheap and disposable, and have sought to improve human resource practices for these workers, to increase their motivation and productivity. Previous studies on human resource management show that improvements in employees’ job embeddedness and job satisfaction enhance their organizational commitment and work motivation, reducing turnover intentions (Mitchell et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2004; Allen and Shanock. 2013).

Job embeddedness represents a broad constellation of influences on employee retention related to three aspects of workers’ relationships to their jobs: links to others, fit with the environment, and sacrifices of material or psychological benefits (Mitchell et al. 2001). Organizational commitment is defined as the strength of an individual’s identification and involvement in a particular organization. It can be characterized by a strong belief in and acceptance of the organization’s goals and values, a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization, and a strong desire to maintain membership in the organization (Mowday et al. 1979). Meanwhile, turnover intentions represent mental decisions intervening between an individual’s attitudes toward a job and whether to stay or leave the organization (Sager et al. 1998). Recent studies on migrant workers in China find that improvement in job embeddedness and commitment to the workplace reduces turnover (Sun and Yang 2012; Wang and Deng 2017; Gan 2018).

Hypotheses and Factory Employee Survey

Based on this conceptual framework we propose three hypotheses to examine in this study. Our first hypothesis is that higher job embeddedness is associated with greater organizational commitment among employees in their workplaces. Second, organizational commitment mediates the negative relationship between job embeddedness and turnover intention; thus, high job embeddedness reduces migrant workers’ turnover intention through organizational commitment. Third, younger and older generations of migrant workers exhibit significant differences in the structure of their organizational commitment.

To examine the mechanism of turnover among migrant workers, we conducted a survey of factory employees in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, in 2014 with support from the local government and university. Suzhou, located in the middle of Yangtze delta, is one of the most developed manufacturing regions in China and is famous for making high-tech products and equipment such as electronics, optical instruments, and fine chemicals. In the first stage of our sampling survey, we chose six manufacturing facilities (three Taiwanese-owned and three owned by domestic private companies). Then, we randomly selected approximately 65 workers from each firm and conducted structured interviews with a total of 390 employees (a response rate of 95.1%). The survey targeted assemblers who had migrated from outside of Suzhou and we excluded those who were not migrants as well as those missing key answers. Thus, our final, valid sample consists of surveys of 313 employees.

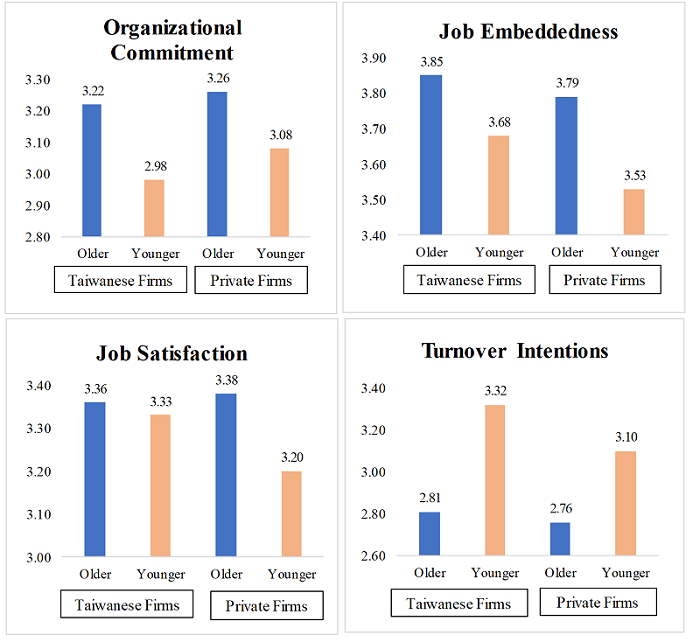

Referring to surveys in previous studies, we prepared a detailed structured questionnaire to measure employees’ awareness of our key latent variables (job embeddedness, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions) using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Simple arithmetic averages of these latent variables are shown in Figure 2. The comparisons of latent variables suggest that the distinction between generations (younger than 25 years and 25 years or older) is more apparent than differences based on firm ownership. For example, the average organizational commitment among older employees in Taiwanese firms is 3.22, which is significantly larger than that among younger workers. The same trend is observed in private firms. Actually, the estimation results of a canonical discriminant analysis exhibit the significant distinctions between generations for all latent variables except job satisfaction.

Figure 2. Comparison of Latent Variables by Ownership and Age Group

Note: The vertical axis indicates the simple arithmetic average for each variable.

Source: Authors’ estimation from a survey of migrant factory workers in Suzhou, China.

Estimation Results and Implications

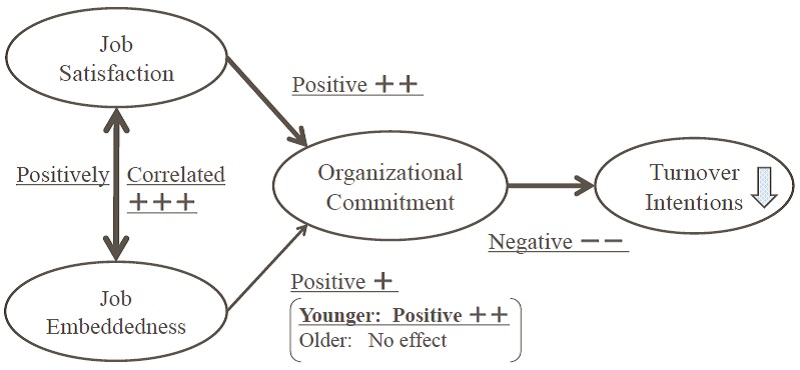

To verify our hypotheses mentioned above, we estimate a framework using Structural Equation Modeling and summarize the major results in Figure 3. The estimation results of entire sample shows both job embeddedness and job satisfaction significantly enhance migrant workers’ organizational commitment in the workplace, and that higher organizational commitment among these workers significantly reduces their turnover intentions. Meanwhile, the results for other specification reveal that job embeddedness has no significant direct effect on turnover intentions. These results support the hypotheses that job embeddedness significantly enhances organizational commitment and organizational commitment mediates the negative relationship between job embeddedness and turnover intentions. Therefore, high job embeddedness could reduce migrant workers’ turnover intentions through improved organizational commitment.

Next, we divide the sample into two age groups (younger than 25 years and 25 years or older) to assess differences between generations. The results show that job embeddedness exhibits significant positive effects on organizational commitment only for the younger age group, while higher organizational commitment significantly reduces turnover intentions in both age groups.

Figure 3. Determinants of Turnover Intentions Using Structural Equation Modeling

Note: The number of “+” and “-” signs indicates the magnitude of the coefficient. Details of the estimation results are shown in the original paper (Hoken, Yamaguchi and Sato, 2022).

Source: Authors’ estimation from a survey of migrant factory workers in Suzhou, China.

These results suggest that manufacturers should offer more detailed job instructions and training to their employees to help them become more proficient in their work and comfortable in the workplace. Recreational activities to promote social communications among employees also appear to encourage embedding in the workplace. It should be noted that these instructions and supports are more beneficial to younger migrant workers for improving their embedding into the workplace, resulting in higher organizational commitment and lower turnover.

Author’s Note:

This column is based on Hisatoshi Hoken, Mami Yamaguchi, and Hiroshi Sato. 2022. “Determinants of Migrant Workers’ Turnover Intentions in China: A Case Study of Manufacturing Factories in Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province” [in Japanese]. Ajia Keizai 63 (2): 2–30. https://doi.org/10.24765/ajiakeizai.63.2_2.

References

Allen, David, and Linda Shanock. 2013. “Perceived Organizational Support and Embeddedness as Key Mechanisms Connecting Socialization Tactics to Commitment and Turnover among New Employee.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 34 (3): 350–69.

Cheng, Zhinmig, Haining Wang, and Russell Smyth. 2013. “Happiness and Job Satisfaction in Urban China: A Comparative Study of Two Generations of Migrants and Urban Locals.” Urban Studies 51 (10): 2160–84.

Gan, Weinyu. 2018. “An Empirical Study of the Identity, Emotional Commitment and Turnover Intention of the New Generation Migrant Workers from the Rural Areas in the Perspective of the Organizational Support” [in Chinese]. Journal of Management 31 (2): 36–49.

Lee, Thomas, Terence Mitchell, Chris Sablynski, James Burton, and Brooks Holtom. 2004. “The Effects of Job Embeddedness on Organizational Citizenship, Job Performance, Volitional Absences, and Voluntary Turnover.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (5): 711–22.

Mitchell, Terence, Brooks Holtom, Thomas Lee, Chris Sablynski, and Miriam Erez. 2001. “Why People Stay: Using Job Embeddedness to Predict Voluntary Turnover.” Academy of Management Journal 44 (6): 1102–21.

Mowday, Richard, Richard Steers, and Lyman Porter. 1979. “The Measurement of Organizational Commitment.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 14 (2): 224–47.

Sager, Jeffrey, Rodger Griffeth, and Peter Hom. 1998. “A Comparison of Structural Models Representing Turnover Cognitions.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 53 (2): 254–73.

Sun, Zhongwei, and Xiaofeng Yang. 2012. “Disembedded Employment Relationship and Turnover Intention of Peasant-workers: Based on a Survey of Peasant-workers in the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta” [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Sociology 32 (2): 98–128.

Wang, Lin, and Sha Deng. 2017. “Study on Turnover Mechanism of New-generation Migrant Workers: From the Viewpoint of Job Embeddedness” [in Chinese]. Rural Economy 2017 (1): 118–23.

Zhao, Liqiu, Shouying Liu, and Wei Zhang. 2018. “New Trends in Internal Migration in China: Profiles of the New-generation Migrants.” China & World Economy 26 (1): 18–41.

Author's Profile

Hisatoshi Hoken is a Professor at School of International Studies, Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan. He received the BA, MA, and PhD degrees in economics from Hitotsubashi University, Japan. He is a former research fellow at IDE-JETRO. His recent publication is “Effects of Public Transfers on Income Inequality and Poverty in Rural China.” China & World Economy 30 (5): 29–48, 2022 (with Hiroshi Sato).

* Thumbnail image: Workers at an electronics factory in Dongguan, China (Shannon Fagan / Photodisc / Getty Images)

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE-JETRO or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.