IDE Research Columns

Column

Japan’s East Asia Economic Strategy toward Economic Revival

Shujiro URATA

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

March 2023

Aside from the serious impact of the coronavirus pandemic, the Japanese economy has been experiencing sluggish growth for several decades, and its prospects are not favorable mainly due to its declining population. One effective way for Japan to revive its economy and achieve growth is to expand and intensify its economic relationship with fast-growing East Asian countries. Japan succeeded in establishing two regional free trade agreements—Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—with these countries. Japan needs to play a role in setting up an effective monitoring system to ensure the implementation and enforcement of commitments by CPTPP and RCEP members. Due to the increased uncertainty in the world economy, Japan is expected to contribute to the reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO) for establishing a rule-based free and open trade environment at the global level so that WTO members can conduct business efficiently and achieve economic growth.

Japan’s Economic Stagnation

The Japanese economy, like that of several other countries in the world, has suffered greatly because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. However, the Japanese economy had been facing various challenges and experiencing low growth even before the outbreak of the pandemic. The GDP growth rate of Japan from 2000 to 2019 was 0.7%, which is not only lower than the growth rate of the world economy (2.8%) but also than that of OECD countries (1.8%). For example, the growth rates of China and the US during the same period were 9.0% and 2.0%, respectively.

Numerous factors can be cited as the cause of Japan’s economic stagnation, including the failure of macroeconomic policies and delays in structural reforms, but one of the leading causes is the rapidly declining birthrate and the increasing aging population. The supply constraint of a decreasing labor force due to demographic difficulties and the resulting slump in demand due to falling incomes are restraining economic activities. Overcoming the demographic problems is vital for the growth of the Japanese economy, and policies must be developed and implemented to achieve this. However, even if measures to deal with the problem are successful, it will take several decades to see results in the form of economic growth. Therefore, it is essential to implement both short- and medium-term measures.

In a situation where the expansion of the domestic market cannot be expected sooner, the expansion of external economic relations, especially with fast-growing East Asian countries, is important for the growth of the Japanese economy.

GVC-Led Dynamic East Asian Countries

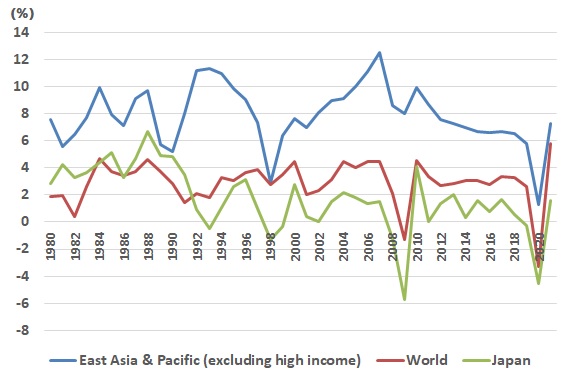

Although East Asian countries were also hit hard by the pandemic in 2020, they had recorded high growth since the mid-1980s, except for the period of the Asian currency crisis in 1997 and 1998 (Figure 1). The high growth can be attributed to several factors, including strong investment, appropriate macroeconomic policies, and a low-wage workforce. Among the most significant contributors was the global value chain (GVC), which was created by foreign direct investments (FDIs) from multinational corporations (MNCs) from the East Asian region, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, as well as Western countries.

Figure 1. Economic Growth Rates for Japan, East Asian Developing Countries,

and the World

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators online (accessed on November 10, 2022)

MNCs established the GVC by shifting from an integrated production system in which all production processes are conducted in one place to an international production fragmentation system in which production processes are broken down by the process and located in countries and regions where the processes can be conducted at the least cost. Through GVCs, MNCs can achieve an efficient production system under which labor, capital, and technology are used most efficiently. In East Asia, these GVCs have resulted in the rapid growth of international trade in parts and components between production bases within the GVC framework, promoting regional economic integration.

The construction of GVCs contributed to the growth of the countries involved. The home countries of MNCs such as Japan were able to expand trade and FDI and use financial and human resources efficiently. Moreover, they were able to receive earnings from overseas operations of MNCs. The host countries of MNCs, such as Thailand, Malaysia, and China, were able to achieve high economic growth not only by expanding production by MNCs but also by increasing productivity through the transfer of technology and management know-how from MNCs to local firms.

Several factors contributed to the construction of GVCs by MNCs. First, MNCs acquired the capability to construct and manage a complicated system of GVCs by accumulating experiences in overseas operations through exporting and undertaking FDI. Second, the cost of conducting foreign trade and FDI declined, facilitating the running of GVC operations by MNCs. Reduction in trade and FDI costs is attributable to several factors. One is the technological progress in transportation and communication services. Another is the deregulation of these services in several Asian countries, lowering trade and communication costs. The liberalization of trade and FDI policies in several East Asian countries also reduced the relevant costs and provided MNCs with a free and open environment for international business. Numerous East Asian countries switched their trade and FDI policies from inward to outward orientation as they witnessed the successful economic performance of Newly Industrializing Economies, such as South Korea and Taiwan, which adopted outward orientation policy. Although trade and FDI policies were liberalized, there are still barriers and further reduction of the barriers is necessary.

Emergence of Region-Wide Free Trade Agreements: CPTPP and RCEP

In the latter half of the 1980s, the movement toward institutionalized regional economic integration gained momentum in various regions of the world. In Europe, the movement that started in the 1950s accelerated—the European Union was established in 1993. In North America, the Canada-US-free Trade Agreement came into effect in 1989, followed by the North American-Free Trade Agreement between the US, Canada, and Mexico in 1994. A Free Trade Agreement (FTA) is a preferential trade policy, which removes tariffs on imports from its members, resulting in an expansion of trade between the FTA members. FTAs in these years increased mainly because of slow progress in the multilateral trade negotiation under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Countries interested in expanding exports to promote economic growth favored FTAs with like-minded countries.

Compared with other regions of the world, the Asia–Pacific was slow to develop institutionally-driven regional economic integration. The first major regional economic integration was the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Free Trade Area in 1993. South Korea and Japan began to demonstrate an interest in FTAs in the late 1990s, as they were concerned with losing their export markets due to an expansion of discriminatory FTAs, which made them adopt FTAs. China became active in pursuing FTAs after it joined the WTO in 2001.

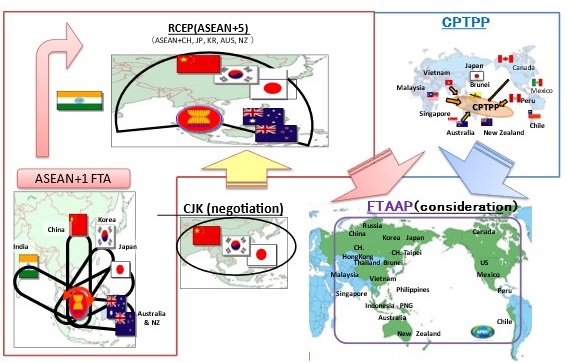

After establishing several bilateral and minilateral (with few members) FTAs, East Asian countries began to discuss region-wide FTAs. They pursued two approaches—one involving East Asian countries only, and the other the countries in the Asia-Pacific region (Figure 2). The former resulted in the RCEP Agreement with 15 East Asian countries (10 member countries of the ASEAN and China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand) in January 2022. RCEP negotiations began in 2012 with the 15 East Asian countries and India, but India withdrew at the final stage because of concern over possible negative impacts on its manufacturing sector from increased imports from China.

Figure 2. Region-wide FTAs in Asia-Pacific: ASEAN+1 FTAs, RCEP, CPTPP,

China–Japan–Korea (CJK) FTA, and FTAAP

Source: The author modified an original figure taken from the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry.

The latter approach resulted in the CPTPP with 11 Asia-Pacific countries—Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. TPP negotiations began in 2010 with the US and these 11 countries, but after reaching an agreement in 2016, President Trump withdrew the US from the TPP. The remaining 11 countries successfully established CPTPP in 2018.

Both CPTPP and RCEP have contributed to the establishment of a rule-based, free, and open trade and investment environment in the Asia-Pacific region, which in turn would promote the establishment and running of GVCs. Both CPTPP and RCEP cover issues important in international economic activities today in a broad and comprehensive manner, including rules on intellectual property rights, government procurement, and e-commerce. The level of liberalization is higher, and the coverage of the issue is greater in CPTPP than in RCEP.

The Japanese government played a constructive role in the negotiations of CPTPP and RCEP, which made these FTAs beneficial to member countries, especially Japanese firms. The FTAs are considered pathways to a free trade area of Asia-Pacific, involving 21 APEC economies.

WTO Reform

Establishing a rule-based, open, and free trade and FDI environment is important for the world to achieve economic growth. It is particularly important for the economic revival and growth of Japan, which faces a declining domestic market. Establishing regional FTAs, such as the CPTPP and RCEP, would certainly contribute to the environment at the global level. To leverage these FTAs, it is necessary to ensure the implementation and enforcement of commitments by the members through an effective monitoring system. Japan should contribute to setting up and running such a system.

Rebuilding a rule-based world trading system under the WTO is of vital importance when increased uncertainty due to geopolitical tensions and possible natural disasters by infectious diseases and climate change threatens all countries. Japan should lead the discussion on WTO reform to achieve this objective.

Author’s Note

This paper builds upon Urata, Shujiro. 2021. “Japan’s Asia-Pacific Strategy: Toward the Revival of the Japanese Economy.” Asia-Pacific Review 28(2): 35–56.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13439006.2021.2012744

Other Relevant Works by This Author

Urata, Shujiro. 2002. “A Shift from Market-Driven to Institution-Driven Regionalisation in East Asia.” Paper presented at the Conference on Asian Economic Integration, Tokyo, April 22 and 23, 2002. https://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/events/02042201/pdf/urata_1.pdf

———. 2019. “FTAs in East Asia from the 1990s to the 2010s Defensive and Competitive Regionalism.” In East Asian Integration: Goods, Services and Investment, edited by Lili Yan Ing, Martin Richardson, and Shujiro Urata, 6–24. London: Routledge.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/oa-edit/10.4324/9780429433603/east-asian-integration-lili-yaning-martin-richardson-shujiro-urata

* Thumbnail photo: Smart City with connected network high-angle image (Hiroshi Watanabe/ Photodisc / Getty Images)

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions to which the author is attached.