IDE Research Columns

Column

Declining Suicide Rates during the Sri Lankan Civil War

Takeshi AIDA

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

March 2023

Many studies produced after the seminal work of Durkheim (1897) have documented a decline in suicide rates during wartime due to increased social integration. However, there remains a need to apply a rigorous statistical approach to determine whether this theory is valid in a modern context. Aida (2020) revisited this issue in the context of the Sri Lankan Civil War. The results showed that during wartime, suicide rates in the target districts were 43% to 52% lower than baseline rates. This finding suggests that even in the modern era, significant social upheavals lead to a decline in suicide rates.

War and Suicide

More than 700,000 people across the globe commit suicide every year, and 77% of these suicides occur in low- or middle-income countries.1 Suicide is a complex social phenomenon that cannot be merely reduced to the actions of a single person. Émile Durkheim, a principal architect of modern sociology, first introduced this perspective in his book Le Suicide (1987) at the end of the 19th century. He argued that the suicide rate is determined by the levels of social integration and moral regulation in a society. To support his argument, Durkheim demonstrated how suicide rates decline during periods of social upheaval, such as war. Indeed, war strengthens social integration and forces people to face a common threat. Consequently, people tend to focus less on their own personal circumstances, leading to a lower suicide rate. Since Durkheim, various studies in sociology, public health, and other fields have confirmed this decline in suicide rates during wartime.

However, there are two remaining challenges that have not been solved by previous studies. First, the nature of war in current times is different from that of Durkheim’s era. Indeed, whereas inter-state conflicts were more common in the late 20th century, in the modern era, civil wars in developing countries now account for a majority of armed conflicts. Second, it is difficult to isolate the effect of wars from other factors that can affect suicide rates. Therefore, the method of comparing suicide rates before and after a conflict, which has often been employed in previous studies, is insufficient. In this context, it is necessary to re-examine Durkheim’s theory using a modern statistical approach.

Suicide Rates during the Sri Lankan Civil War

Aida (2020) examined the relationship between civil war and suicide rates by applying modern econometric methods to analyze the case of the Sri Lankan Civil War. The Sri Lankan Civil War was fought from 1983 to 2009 between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, an ethnic Tamil militant group, and the Sri Lankan Government. Armed conflicts occurred mainly in the northern and eastern regions of the country, which are majority-Tamil areas. Moreover, during the civil war, the severity of damage varied greatly by district. Therefore, in addition to comparing suicide rates before and after a conflict, it is also possible to incorporate cross-sectional differences in suicide rates between disputed and non-disputed areas. This approach enables us to isolate the effect of civil war from other factors based on the assumption that the changes in unobserved factors will be parallel in both areas.

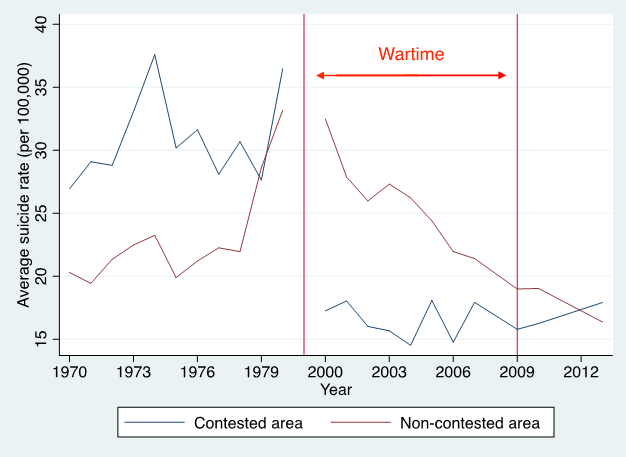

Figure 1. Trends in the Suicide Rate of Contested and Non-contested Districts.

The figure shows the trend of average suicide rate per 100,000 people in the pre-war (1970

–80), wartime (2000–09), and post-war (2010 and 2013) periods for the contested and

non-contested districts (cited from Aida 2020).

This study involved constructing a unique panel dataset of annual suicide rates for each district from various data sources that covered 22 districts (as per pre-war administrative divisions). Due to limited data availability, the pre-war period is represented by data from 1970 to 1980, and the post-war period is represented by data from 2000 to 2013. Figure 1 illustrates the change in the suicide rate (per 100,000) in contested and non-contested districts. Suicide rates were lower in non-contested districts during the pre-war period, and the trend line is nearly parallel to that of the contested districts. However, during wartime, the trends are reversed: Contested districts exhibited lower suicide rates. These initial observations confirm the hypothesis that suicide rates decline during wartime. A formal regression analysis to estimate the “difference in differences” also confirmed that during wartime, suicide rates in contested districts declined by 11.8 to 14.4 points compared to baseline measurements.2 This is equivalent to a 43%–52% decrease in suicide rates, suggesting that war environments have a significant impact on suicide rates. The effect was more pronounced among men (55%–61% decrease) than women (24%–33% drop), which is also consistent with previous studies.

The results of several additional statistical exercises are relevant to this discussion. First, the intensity of conflicts varies even during wartime. Therefore, we re-defined the wartime period to exclude the ceasefire period (2002–06). However, we found that this did not influence the decline in suicide rates. Second, to address data reliability related to the contested area during wartime, we removed data from the sample for districts where data collection is expected to have been difficult. However, the estimation results still confirmed the negative relationship. Third, we incorporated the number of war casualties into the analysis to demonstrate that more intense conflicts are associated with lower suicide rates. Fourth, we controlled for suicide rates in neighboring districts and confirmed that spatial spillover effects are not salient enough to change the findings. These results indicate that the estimated decline in suicide rates is less likely to be spurious.

Although the above analysis established the effect of civil war on suicide rates, there are several concerns that were difficult to capture directly via statistical analysis. For example, due to limited data availability, the current study could not fully control for the effect of economic factors, such as GDP and the unemployment rate. It is known that suicides tend to increase during an economic downturn. As it is likely that the districts affected by war also experienced an economic downturn, the decline would be more salient if we could control these factors. Previous studies also suggest that a ban on pesticides, which are often used to commit suicide, coincided with the decline in suicide rates in Sri Lanka (Gunnell et al. 2007). However, in our analysis, we assumed that such national-level policy changes would have occurred in all districts and, therefore, would have had little effect on the estimated impact. Moreover, it could be suspected that ethnic composition can confound the estimated effect; however, the available data confirms no systematic difference between Tamil and other ethnicities.

Implication

The study revisited a classical theory using modern econometric methods in a contemporary social context. Despite data limitations, our detailed analysis demonstrated a significant decline in the suicide rate during the Sri Lankan Civil War, suggesting that massive social upheavals do lead to a decline in suicide rates. Nevertheless, this finding in no way justifies civil wars. Although the current study analyzed civil wars, a significant decrease in suicide was also confirmed in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Pirkis et al. 2021). In both cases, it is expected that the presence of a shared threat motivated people to focus on collective action, which can result in higher social integration. However, further analysis of the underlying psychiatric mechanism must be addressed in future research.

Note

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- The difference-in-difference is a statistical approach that compares the before-after changes in outcomes between the treatment and the comparison groups, assuming that both groups have a parallel trend in the outcome.

Author’s Note

This research column is based on Aida, Takeshi. 2020. “Revisiting Suicide Rate during Wartime: Evidence from Sri Lankan Civil War.” PLoS ONE 15(10): e0240487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240487

References

Durkheim, Émile. 1897. Le Suicide: Etude de Sociologie. Paris: Alcan. Translated by Richard Sennett as On Suicide (London: Penguin Classics, 2007).

Gunnell D., R. Fernando, M. Hewagama, WDD. Priyangika, F. Konradsen, and M. Eddleston.“The Impact of Pesticide Regulations on Suicide in Sri Lanka.” International Journal of Epidemiology 36: 1235–42.

Pirkis, Jane, Ann John, Sangsoo Shin, Marcos DelPozo-Banos, Vikas Arya, Pablo Analuisa-Aguilar, Louis Appleby et al. 2021. “Suicide Trends in the Early Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Preliminary Data from 21 Countries.” Lancet Psychiatry 8: 579–88.

Author’s Profile

Takeshi Aida is a research fellow at Institute of Developing Economies (Ph.D. in Economics). His areas of research include development, behavioral, and agricultural economics. He has published articles in Scientific Reports, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, BMC Public Health, Applied Economics Letters, PLoS ONE, Oxford Economic Papers, World Development, Journal of Agricultural Economics, and Journal of Development Studies.

* Thumbnail photo: Vianni Sunset Travellors (trokilinochchi, CC Attribution 2.0 Generic, via Wikimedia Commons)

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.