IDE Research Columns

Column

The US-China Trade War and Prospects for ASEAN Economies

Ian COXHEAD

University of Wisconsin-Madison

May 2022

As the Biden administration enters its second year, frictions between the US and China show no sign of abating and may even deteriorate further. Prospects for restoration of pre-trade war economic relations between the world’s two largest economies remain dim. Other Asia-Pacific economies are involuntarily affected by the policies of their largest trading partners. This note provides context by summarizing relevant aspects of the US-China conflict, and explores short and long run implications for trading partners with particular focus on spillovers to ASEAN economies.

Bilateral Conflicts over Trade—and More

Disputes over politics, human rights and cybersecurity are increasingly prominent features of the US-China relationship. High-level meetings between the Biden administration and its Chinese counterparts have ended with open disagreement on issues from Xinjiang to the South China Sea, and from state trading companies to spyware. Senior officials on both sides have gone on record using strongly negative language to characterize the relationship. The US-China Tensions index, a summary measure of bilateral relations, has risen to historically high levels (Rogers, Sun and Webster 2021).

Bilateral frictions and rhetoric over political issues are hardly new. But so long as they remain unresolved, nearly all Trump-era US import tariffs and retaliatory Chinese measures also remain in place. While the U.S. has moved ahead with relaxing steel tariffs that Donald Trump imposed on the EU and Japan, there is no sign of a trade policy thaw with China.

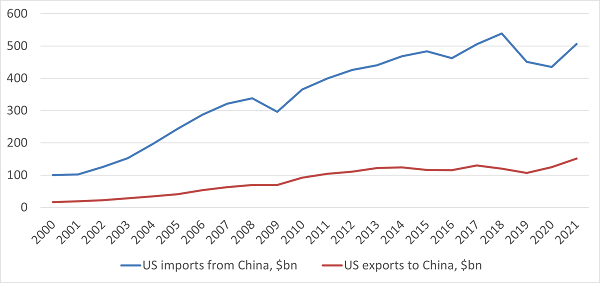

The trade war has imposed significant costs on both economies. In 2018-19, US imports from China fell by 16.3% to a level not seen since 2013, and exports to China fell by 11.5%, to a level last matched in 2011. Trade (especially US exports) recovered in 2021 but imports are back only to their 2017 level (Figure 1). The two-year “Phase I” trade deal that ran from January 2020 to December 2021 imposed unrealistically high sector-level targets on the value of Chinese imports from the US. It has fallen predictably short of those goals despite a surge in Chinese farm imports from the US, but more importantly, this managed trade deal does nothing to regularize or restore a stable trade partnership (Bown 2022). In both countries but especially in the US, politics rather than economic interests dominate policymaking where bilateral relations are concernedi. The world’s largest (and since 2000, fastest-growing) bilateral trade and investment partnership is not itself in peril, but its continued expansion is certainly in question.

Figure 1: US-China bilateral trade, 2000-2021.

Source of data: US Census Bureau

Spillovers to Asia-Pacific Trade

The US and China are huge trading powers with discretion to choose policies that maximize domestic gain. But what are the consequences of this dispute for the rest of Asia-Pacific, where these countries’ actions amount to exogenous changes in trade, prices, and investment incentives?

ASEAN countries in particular are susceptible to changes in Asia-Pacific trade. Southeast Asia has a long history of experiencing trade ‘shocks’ from Northeast Asia leading to significant changes in regional comparative advantage and growth. In the 1980s, the post-Plaza Accord boom in inward foreign investment was the catalyst for export-oriented industrialization in the region. Subsequently, China’s “open door” growth and trade boom induced massive increases in natural resource exports in addition to creating many new opportunities for global value chain (GVC) participation (Coxhead 2007; Phung, Coxhead and Lian 2015). The ASEAN region today finds itself vulnerable to spillovers from a bilateral dispute that threatens to diminish GVC activity and promote reshoring, thereby weakening an important pillar of regional economic growth.

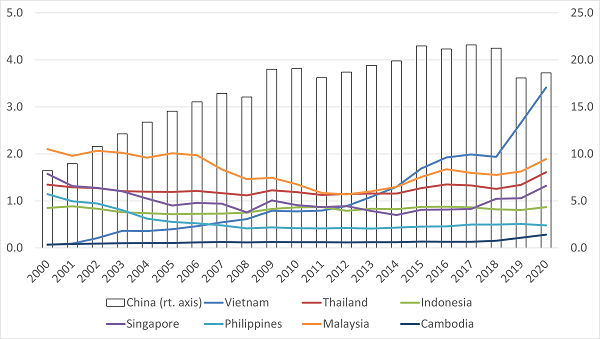

The impacts of the bilateral trade dispute take several forms. First, China and the US together account for more than 35% of global GDP, so to the extent that trade and investment frictions reduce growth in each, we should expect slower worldwide economic growth (the full extent of this decline has been obscured by Covid-related changes since 2020 and will only become clear after the pandemic has receded). Second, China and the US are the largest export destinations for most ASEAN countries—and much of what the region exports to China subsequently enters China-US trade after further processing or assembly (Athukorala 2011). Therefore, bilateral trade reduction cascades back to Southeast Asia through regional supply chains. Third, and more positively, there has been some displacement of production and investment away from China, with the largest effects felt in regional trading partners. In 2018-20 ASEAN’s share in the value of US imports rose by 2.6%, coincidentally the same amount by which China’s share declined. Each of ASEAN’s large and trade-dependent economies except the Philippines recorded increases in their shares of US imports during 2018-20 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: China and Southeast Asian country shares in the value of US imports, percent.

Source of data: US Census Bureau

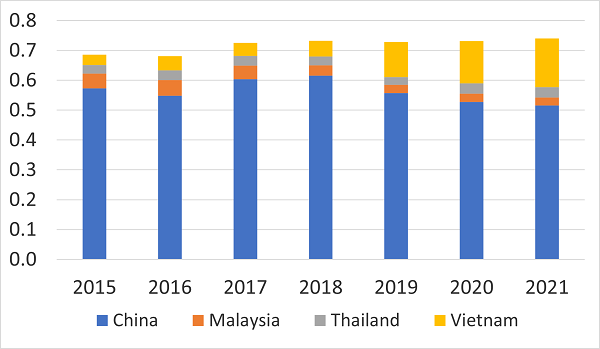

The news is by no means all bad. Vietnam is probably best-placed to benefit from trade and investment diversion. Certainly, it has experienced by far the greatest growth in trade and FDI. Its share in US imports, already on a rapidly rising path, jumped from 1.9% in 2018 to 3.4% in 2020. While China’s share in US imports of telecommunications equipment (which includes mobile phones) fell from its peak of 61.5% in 2018 to 52.8% in 2020, Vietnam’s share rose from 5.2% to 14% in the same period (Figure 3). From 2020 to 2021 alone, Vietnam jumped five places in the world rankings of FDI inflows, joining the top 20 list at no. 19 (UNCTAD 2021).

Figure 3: Shares in US imports of telecommunications equipment (SITC 764).

Source of data: US Census Bureau

Vietnam may be a Southeast Asian outlier, however, as its own reforms have generated a “sweet spot” of openness to FDI with low labor costs. It is not so clear that other regional economies can expect much gain from the bilateral conflict. Slower worldwide economic growth will undermine investment and job growth everywhere. Countries more closely linked into China-centered supply chains producing for the global market are most likely to suffer, first because of the overall trade growth slowdown, and second because of China’s own efforts to domesticate its manufacturing supply chain. For example, the Trump years saw static or declining values and shares of US telecoms equipment imports sourced from traditionally dynamic exporters such as Thailand and Malaysia—as can be seen in Figure 3.ii

Implications for the Longer Term

As US-China trade tensions persist, their impacts also extend beyond current-period flows. Strong policy continuity from Trump to Biden has added momentum to policy initiatives in both countries that threaten to bake in home-market biases in procurement, contracting, and commercial practices—for example, “Made in China 2025,” and “Buy American” policies for federal procurement. The latter sets minimum domestic content requirements for federal government procurement and is currently slated for further strengthening (CSIS 2021; The Guardian, 2021). Made in China 2025 and its more recent expression, the so-called Dual Circulation Strategy, aim to move China from an export- and investment-led economy to one based on technology and innovation and to “reduce risks tied to import dependency” (Zhang 2020). Such reshoring policies are politically appealing and are presumably seen in each country as delivering benefits, inclusive of perceived political dividends and reduced risk, which exceed their economic costs. In the case of China, the new industrial policies reinforce substitution of domestic for imported inputs in the manufacturing supply chain (Kee and Tang 2016), a move that will hurt ASEAN exporters of parts and components such as Thailand and Malaysia.

Certainly, reshoring policies in China and the US cannot be expected to increase third-country export demand through international supply chain diversification. These policies create incentives to substitute domestic production for all imports regardless of source. So third countries whose exports are dependent on the vigor of the Asia-Pacific trading system may find that the long-term rollback of interdependence between China and the US, if it occurs, need not translate into greater opportunities for trade with either country. For so long as the US and China hold their bilateral trade hostage to other policy goals, the developing countries in their closest economic orbits will necessarily face diminished opportunities for specialization, and therefore also for growth.

Ian Coxhead, Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Former Executive Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

References

Athukorala, Prema-chandra. 2011. “Production Networks and Trade Patterns in East Asia: Regionalization or Globalization?” Asian Economic Papers 10(1): 65-95.

Bown, Chad P. 2022. “China Bought None of the Extra $200 Billion of US Exports in Trump’s Trade Deal.” https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/. Last accessed Feb 10, 2022.

Coxhead, Ian. 2007. “International Trade and the Natural Resource ‘Curse’ in Southeast Asia: Does China's Growth Threaten Regional Development?” World Development 35(7): 1099-1119.

CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies). 2021. "Buy American, Again." January 28. https://www.csis.org/analysis/buy-american-again.

Kee, Hiau Looi, and Heiwai Tang. 2016. “Domestic Value-Added in Exports: Theory and Firm Evidence from China.” American Economic Review 106(6): 1402-36.

Phung, Thu Trang Phung, Ian Coxhead, and Chang Lian. 2015. “Lucky Countries? Internal and External Sources of Growth in Southeast Asia, 1970-2010.” In Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian Economics, edited by I. Coxhead, 60-86. Oxfordshire (UK): Routledge.

Rogers, John, Bo Sun, and Chris Webster. 2021. “US-China Tensions.” VoxChina,

http://www.voxchina.org/show-3-227.html. Last accessed Feb 10, 2022.

Rogin, Josh. 2022. “Biden Doesn’t Want to Change China. He Wants to Beat It.” Washington Post, February 13. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/02/10/biden-china-strategy-competition/

The Guardian. 2021. “Biden Steps Up “Buy American” Program.” July 28. https://guardian.ng/news/biden-steps-up-buy-american-program/.

UNCTAD. 2021. World Investment Report 2021. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf.

Zhang, Zoey. 2020. “What is China’s Dual Circulation Strategy? And Why Foreign Investors Should Take Note.” Insight Magazine, Nov/Dec. https://www.amcham-shanghai.org/en/article/what-chinas-dual-circulation-strategy

i As one recent review states it, “Restraining China is now a multi-administration, bipartisan strategy that stands among the most important foreign policy adjustments since the end of the Cold War” (Rogin 2022).

ii In some cases—most especially Vietnam, but possibly other countries as well—there is also a concern that part of the export increase may be explained not by expanded domestic production but by the re-export of items produced in China.

*The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

**Thumbnail image: China-US trade, China-US relations, Dock crane - stock illustration (GettyImages)