IDE Research Columns

Column

Economic Resilience and Changes in Global Production Structure

Yoshihiro HASHIGUCHI

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

November 2022

When countries face adverse economic shocks, economic agencies (i.e., firms and governments) are expected to mitigate the negative impact. This study (Hashiguchi et al. 2021) examines how countries’ production and demand patterns change when tackling shocks, arguing that the answer depends on their resilience to economic shocks. This study uses the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s annual Inter-Country Input–Output tables from 1995 to 2011 to investigate how country-level final demand shocks relate to production and demand patterns changes. We found that, during the 2009 global economic crisis triggered by the burst of the US housing bubble, countries were more resilient to negative shocks if they could prop up the economy through the domestic service sectors instead of domestic goods and foreign sectors. The substitutability between goods and service sectors and domestic and foreign sectors is essential for understanding the potential risk to a country’s domestic economy from shocks abroad, including economic, environmental, health-related, or political.

Background

Most countries are dependent on others through economic networks, implying that economic shocks are not confined to a country but rather cascade to other countries, affecting the output of other sectors and regions (Berdiev and Chang 2015; Rana et al. 2012; Acemoglu et al. 2012; Carvalho 2014; Roson and Sartori 2016). Economic resilience, defined as the ability of a country to alleviate economic losses in the aftermath of shocks, likely depends on the flexibility of global production networks to shocks. Based on Hashiguchi et al. (2021), this study empirically examines how the production and demand structure tends to change due to country-level final demand shocks and whether such structural changes contribute to containing domestic economic losses.

Expected Behavior of Economic Agents

Most government reactions to adverse shocks are on the final demand side. For example, a government is expected to increase public final expenditure and investment, support private investment by changing interest rates, create a stimulus package for household consumption, or provide tax incentives and subsidies on production. Conversely, firms’ reactions are expected to change the production structures. For example, firms are likely to change the amount of labor and capital inputs and procurement patterns of intermediate inputs. These changes in economic agents’ behavior affect the economic supply and demand structure and can be associated with the degree of economic resilience.

How to Measure Economic Resilience to Shocks?

Previous studies use global input–output tables, which help evaluate the impact of economic shocks; however, they assume that production and demand structures (i.e., procurement patterns of intermediate inputs and markets for selling/buying final goods and services) are stable even when final demand shocks occur. Moreover, previous studies only reveal the marginal impacts of changes in final demand. As mentioned above, economic agents are expected to react to shocks by changing their procurement patterns and market destinations, thereby reducing the negative impact.

This study captures the changes in production and demand structure by using the annual Inter-Country Input–Output (ICIO) tables, measuring the contribution of changes in procurement patterns and market destinations to value-added growth for each sector and country. Furthermore, this study investigates how country-level final demand shocks are related to structural changes and domestic value-added. The ICIO data are obtained from the 2015 edition of OECD ICIO tables, covering all OECD countries and 27 nonmember economies (including all G20 countries) from 1995 to 2011.

The Role of Structural Change in Preventing a Steep Decline in Economic Performance

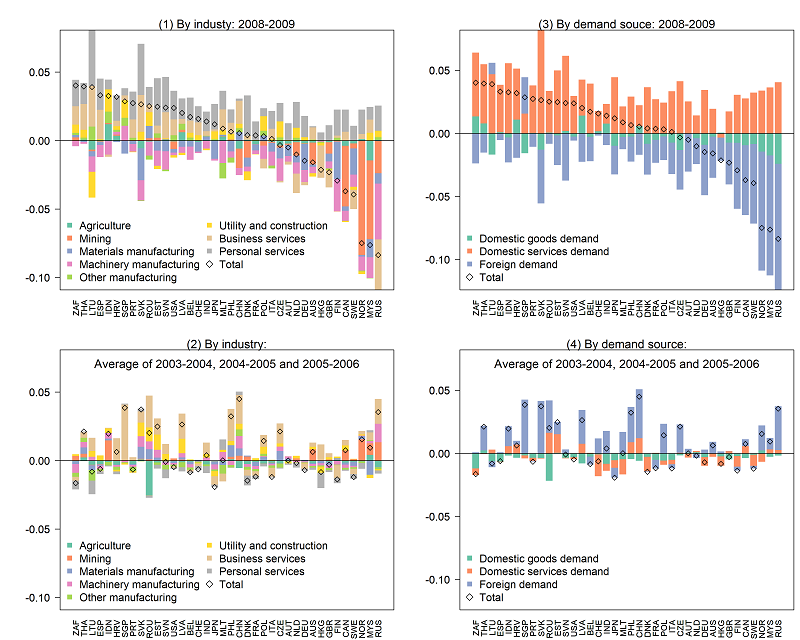

Panels (1) and (3) of Figure 1 show the contribution of changes in production and demand structure to value-added growth for 2008–2009, indicating how each country’s production and demand structure changed during the 2009 global economic crisis. Panels (2) and (4) show the average contribution of structural changes to value-added growth for 2003–2004, 2004–2005, and 2005–2006, indicating the trend of structural changes before the global economic crisis. The bar charts break down the contribution by eight industries (Panels [1] and [2]) and by final demand source (Panels [3] and [4]); a positive (negative) value means that the structure changed to increase (decrease) value-added growth, that is, structural changes positively (negative) contributed to value-added growth. For example, Spain (ESP) experienced a sharp decrease in value-added growth in the 2008 crisis. Panels (1) and (3) show structural change’s positive contribution, implying that a decrease in value-added growth was significant but less than expected. The structural changes during the crisis led to the domestic service sectors producing more value-added than before the crisis, which helped mitigate the negative impacts.

Figure 1. Contribution of Changes in Production and Demand Structure to Value-Added

Growth When Final Demand Shocks Occur

Note: National Currency at constant prices. The vertical axis contributes to changes in production and demand structure to value-added growth. The bar charts show a breakdown of the contribution by eight aggregated industries (Panels [1] and [2]) and by final demand source (Panels [3] and [4]). Diamonds indicate the total contribution.

Source: Hashiguchi et al. (2017, 2021).

First, Panels (1) and (2) reveal that production and final demand structures tend to change to reduce the negative impact of final demand shocks. The significant economic downturn in 2008–2009 increased dependence on the value-added of service sectors and decreased dependence on the value-added of goods sectors. Therefore, the temporary shift from the goods to services sectors seems to play a vital role in reducing the economic downturn. Second, Panels (3) and (4) show that the structure tends to change temporarily in the downturn phase; the shock increases the value-added induced by domestic services demand and decreases the value-added induced by both domestic goods demand and final foreign demand. This increase in the dependence on domestic services demand contributes to containing domestic economic losses. As Panel (4) indicates, before the global economic crisis, many countries’ production and final demand structures changed so that their dependence on foreign demand increased while their dependence on domestic goods decreased. This variation implies that the world economy tends to deepen and expand interdependence among countries and that globalization helps increase value-added induced by foreign demand; however, the dependence on foreign demand decreased during the crisis, while reliance on domestic services increased (Panel [3]). This result indicates that the structural changes negatively impacted final demand, increasing dependence on demand for domestic services. In sum, domestic services played a key role in preventing a steep decline in economic performance. Econometric regression analysis confirms the above findings of decomposition analysis.

Summary and Policy Implications

When negative final demand shocks occur, the production and final demand structures change temporarily to decrease the dependency on both domestic goods demand and final foreign demand while simultaneously increasing the dependency on domestic services demand. Increasing domestic services dependency can mitigate economic losses from adverse final demand shocks. Countries that can prop up the economy through the domestic service sectors instead of domestic goods and foreign sectors are more resilient to negative final demand shocks.

We next examine why dependency on foreign demand decreases during a downtown phase. In this phase, domestic goods demand is likely to decrease more than services if the income elasticity of demand for goods (i.e., a measure of how responsive demand for goods is to a change in income) is higher than those for services. This decrease in the demand for domestic goods can lead to a fall in international trade because foreign demand is mainly for goods, and the share of service trade is relatively small; therefore, a decline in the demand for domestic goods in many countries can lead to a decline in the dependency on final foreign demand. In a downturn, the domestic service sector’s propping up seems to play a critical role in temporarily containing the negative shock.

These findings have implications for building a resilient supply chain. Procurement patterns of intermediate inputs and markets for selling/buying final goods and services have become increasingly dependent on foreign supply and demand. Globalization can undoubtedly boost economic growth; however, countries with limited scope to support their economy through domestic supply and demand are more susceptible to adverse shocks in foreign production and consumption. Recently, governments have been concerned about a policy that expands supply sources and increases domestic procurement to enhance economic resilience. Such policy measures play a key role in propping up the economy and preventing a steep decline in economic performance. More importantly, we need to understand the substitutability between domestic and foreign sectors to evaluate the potential risk to a country’s domestic economy from shocks abroad. Countries with higher substitutability will likely alleviate economic losses after shocks. However, a policy for enhancing substitutability among sectors may lead to increasing economic inefficiency. Governments must understand the potential tradeoff between economic resiliency and efficiency.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Vasco M. Carvalho, Asuman Ozdaglar, and Alireza Tahbaz-Salehi. 2012. “The Network Origins of Aggregate Fluctuations.” Econometrica 80(5): 1977–2016.

Berdiev, Aziz N., and Chun-Ping Chang. 2015. “Business Cycle Synchronization in Asia-Pacific: New Evidence from Wavelet Analysis.” Journal of Asian Economics 37: 20–33.

Carvalho, Vasco M. 2014. “From Micro to Macro Via Production Networks.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(4): 23–48.

Hashiguchi, Yoshihiro, Norihiko Yamano, and Colin Webb. 2017. “Economic Shocks and Changes in Global Production Structures: Methods for Measuring Economic Resilience.” OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers no. 2017/09. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/17d0694b-en

———. 2021. “How Thick is Your Armour? Measuring Economic Resilience to Shocks in Global Production Networks.” Economic Systems Research. Published online: 12 Aug 2021. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09535314.2021.1958764

Rana, Pradumna B., Tianyin Cheng, and Wai-Mun Chia. 2012. “Trade Intensity and Business Cycle Synchronization: East Asia versus Europe.” Journal of Asian Economics, 23(6): 701–6.

Roson, Roberto, and Martina Sartori. 2016. “Input–Output Linkages and the Propagation of Domestic Productivity Shocks: Assessing Alternative Theories with Stochastic Simulation.” Economic Systems Research 28(1): 38–54.

- For example, the Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry in Japan mentioned that “we need to make supply chains more robust and diverse, broadening our supply sources and increasing domestic production” (Reuters news, June 9, 2020).

*Thumbnail image: Finance problem concepts (Yuichiro Chino/ Moment/ Getty Images)

**The views expressed in the columns are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions to which the authors are attached.