レポート・報告書

アジ研ポリシー・ブリーフ

No.153 India's increasingly protectionist trade policy

- What are the characteristics of goods subject to increased tariffs? -

Kohei Shiino

PDF (468KB)

- Since 2018, India has intermittently raised its tariffs. India did not join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement, signed in November 2020.

- Tariffs were increased for a total of 2,319 items between the base year, 2017, and 2019, representing 45.3% of the total number of items subject to ad valorem tariffs, while the average tariff rate increased from 13.5% in 2017 to 17.3% in 2019.

- Although tariffs have increased across a wide range of industries, the most substantial increases have been for labor-intensive goods, such as sewn products and footwear, goods in which India has traditionally had a comparative advantage.

Since 2018, India's Modi administration, which opted not to sign the RCEP, has raised the average tariff rate. India's withdrawal from the RCEP can be viewed as the result of the protectionist trade policy present in the Modi administration. This paper examines the characteristics of these tariff increases.

India's decision to opt out from the RCEP

Prime Minister Modi, who declined to sign the RCEP in November 2020, had pointed out at the RCEP summit in November 2019 that there were “significant outstanding issues,” and the joint summit statement announced that India's final decision would depend on satisfactory resolution of these issues. According to information published in the press, India's outstanding issues include the treatment of base year, special safeguards, rules of origin, free flow of data, and investment. However, almost none of the elements that would have resulted in India's withdrawal can be found in the RCEP agreement that was actually signed. India's withdrawal from the RCEP can be attributed to the “China factor,” namely, avoiding the signing of an FTA with China, with which India has a large trade deficit and diplomatic challenges, and the “dairy factor” of strong opposition from the dairy sector, a major domestic employer, which have increased political costs (Shiino 2021).

India’s External Affairs Minister Jaishankar has pointed out that the FTAs has been to de-industrialize some sectors and that trade liberalization has not led to the development of domestic manufacturing.

The Modi administration has intermittently raised tariffs on a wide range of items since 2018. Following the trend of economic reform since 1991, the Vajpayee (1998–2004) and Manmohan Singh administrations (2004–2014) lowered applied tariffs and promoted FTAs, but the Modi administration has yet to conclude any FTAs, including withdrawal from the RCEP, and has turned to raising tariffs.

Characteristics of tariff increases since 2018

What items have been subject to tariff increases by the Modi administration, by how far have tariffs been increased, and how can they be characterized? The WTO tariff database will be used to examine these questions.

Using the data at 6-digit HS codes that can be obtained for 2017–2019 from the WTO database (HS2017, 5,386 items in total) and excluding goods for which specific duty -which are difficult to convert to tariff rates- is applied or no tariff rate is recorded from the same period, this analysis covers 5,119 items subject to ad valorem tariffs.

The average tariff rate for India as a whole (a simple MFN-based average) was 38.7% in 1996, for which statistics are available in the WTO database, but this rate has been reduced over the years, hovering between 12 and 13% from 2010 to 2017. The Modi administration raised this rate from 13.5% to 17.1% in 2018, however, and again to 17.3% in 2019. India's bound tariff rate (the maximum tariff rate above which a country commits not to raise its tariff rates) under the WTO remains 50.8%, and hence India has significant margin for raising tariffs under its WTO commitments.

This average tariff rate level (2019) is significantly higher than for major East Asian countries such as China (7.6%), Thailand (9.3%), Indonesia (8.1%, 2018), the Philippines (6.1%), and Vietnam (9.5%, 2020), making India's high tariffs conspicuous.

Tariffs were increased for a total of 2,319 items between the base year, 2017, and 2019, representing 45.3% of the total number of items subject to ad valorem tariffs. Meanwhile, only 30 items saw tariff reductions.

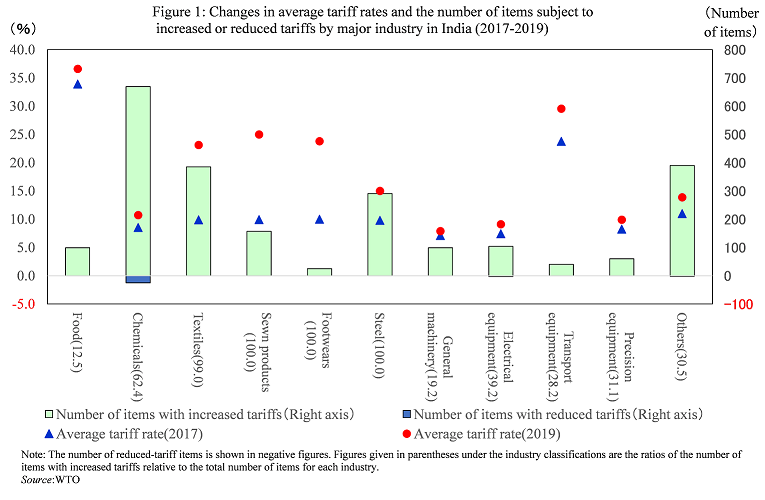

Tariff increases have spanned a wide range of industries; items for which increases have been particularly pronounced include sewn products and footwear, items in which India has traditionally had a comparative advantage, with the average tariff rate for the former increasing from 9.9% in 2017 to 25.0%, and the tariff rate for the latter increasing from 10.0% to 23.8%, both significant increases (Figure 1). Tariffs on textile products such as yarn and fabric have also been raised from 9.9% to 23.1%. In addition, tariffs on industries with a degree of domestic production base, such as steel and transportation equipment, have been raised significantly, while those on electrical equipment, general machinery, and precision equipment for which there is a high dependence on imports, have only been raised slightly.

If we look to the ratio of the number of items subject to increased tariffs against the total number of items in each industry, tariffs on all items falling under sewn products, footwear, and steel have been raised, alongside 99% of textile items. That ratio is only 27.2% for machinery and equipment (general machinery, electrical equipment, transport equipment, and precision equipment), however, indicating that tariffs on such items have been raised selectively.

While a certain rationale can be afforded to tariff increases, such as the protection of infant industries, the fact that India’s tariff increases have spanned most industries and have been particularly pronounced for labor-intensive goods, where India has traditionally had a comparative advantage, can be characterized as protectionist policy.

A disregard for WTO commitments

Some of the items for which India has raised tariffs have been subject to a dispute panel at the WTO. This is because of the possibility that India is violating GATT Article II (Schedules of concessions) by raising tariffs on some information and communications equipment, such as smartphones, despite having committed to levy no tariffs on such items in the schedule of concessions.

Of these disputes, if we look at smartphones, India has raised tariffs on such items by 20% in 2018. This is thought to be aimed at boosting local production of such products, which has been developing since the mid-2010s.

There is certainly no denying the potential existence of a “developing infant industries” rationale to raising tariffs in the short term, but the Indian government has provided a subsidy scheme for the local production of smartphones using the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme, and levelheaded policy decisions are required as to whether it is really necessary to go as far as raising tariffs. The expansion of India's smartphone market has also generated economies of scale, which may have led to progress in local production in recent years. At a minimum, India's apparent disregard for its WTO commitments is problematic.

“Make in India” initiative with limited results and imports from China

In regard to tariff increases, Finance Minister Sitharaman has thus far cited in her budget speeches the goal of promoting domestic production and levelling the playing field between imported and domestic products.

Both in 2020 and 2021, tariffs have been reduced for some raw materials, while tariffs have been increased primarily for industrial goods. In 2020, tariffs were increased for certain items including footwear, furniture, stationery, toys, and mobile phone parts, and in 2021, tariffs were increased for certain items including plastic products, leather goods, some auto parts, LED parts, solar inverters, and solar lanterns.

Since coming to power in 2014, the Modi administration has sought to promote India's manufacturing sector through the “Make in India” initiative. While a measure of progress has been made in recent years, such as the local production of smartphones referenced above, “Make in India” has yet to produce any conspicuous results overall, with the share of GDP accounted for by manufacturing instead falling from 16.3% in FY2014 to 14.7% in FY2019.

Moreover, imports from China, particularly for industrial goods, increased from 2014 to 2018. India's trade deficit with China accounts for 32.8% of its total trade deficit (2019), and when narrowed down to the balance of trade in machinery and equipment, 64.6% of India's trade deficit is with China. India has a trade deficit with China even for trade in sewn goods and footwear, goods for which India has a degree of production base, and China is India's largest source of imports. India can be assumed to be aware that the increase in imports from China is impeding the success of “Make in India,” and that this is a factor driving tariff increases and even withdrawal from the RCEP agreement.

In this context, tariffs are being raised under the banner of promoting manufacturing. From India's point of view, the liberalization of trade that has occurred has hindered the promotion of its manufacturing industry, and it is now changing direction toward a policy of thorough protection for its infant industries. In the long run, however, India's industries are at risk of losing competitive strength as a result of this policy.

The Modi administration seeks a “Self-reliant India”

In 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Prime Minister Modi launched the vision of “Self-reliant India.” Self-reliant India is positioned as a vision that strengthens “Make in India” and places greater emphasis on domestic production. Since then, manufacturing sector policy has been strengthened so as to provide subsidy incentives for local production, including the expansion of industries covered by the PLI scheme. The risk of further tariff increases under the banner of a self-reliant India remains a concern going forward, however.

The RCEP, which India declined to sign, contains a framework for India's future participation and includes provisions for preferential treatment for India (while new members may only join the RCEP 18 months after it comes into effect, India may join immediately, and may participate as an observer at RCEP meetings). However, in addition to the China factor and the dairy factor, the Modi administration's trade policy makes India's prompt participation difficult. Nevertheless, India has shown an interest in increasing the resilience of its supply chain in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a realistic course for India would be to cooperate in areas such as digitalization, facilitation, and diversification of trade. Its participation in a regional FTA such as the RCEP should also be encouraged in the mid to long term.

Trade diversion effects through existing FTAs

India's tariff increases have also increased the value of using the existing FTAs that India has already concluded. India has concluded FTAs with RCEP signatories such as Thailand (2004, 83 items only), Singapore (2005), ASEAN (2010), South Korea (2010), Malaysia (2011), and Japan (2011), and India's tariff increases have increased the preferential margins of these existing FTAs (applied tariff rates − preferential tariff rates under FTAs), and are likely to create trade diversion effects.

Particularly in East Asia, many items are exported after intermediate goods such as textile products imported from China are processed, as typified by ASEAN's garment industry. For example, large quantities of electrical equipment and general machinery are exported from Southeast Asia to India, and Chinese-made components are believed to be used in these exports. The trade diversion effect from China to third-party countries created by India's tariff increases may also create trade diversion effects for China's intermediate goods through the supply chain from China to third-party countries.

(Kohei Shiino / Takushoku University)

<References>

- Shiino, Kohei (2021) “India's Trade Policy in the RCEP Negotiations: What are India's outstanding issues?” Contemporary India Forum No. 49, Spring 2021, pp. 13−26. [in Japanese]

- WTO“DS584:India-Tariff Treatment on Certain Goods,” (https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds584_e.htm, Last accessed on September 24, 2021).

* The author would like thank Dr. Hitoshi Sato, Director-General, Research Operations Department, IDE-JETRO, for his valuable comments and suggestions.

本報告の内容や意見は執筆者個人に属し、日本貿易振興機構あるいはアジア経済研究所の公式見解を示すものではありません。