IDE Research Columns

Column

How Did Political Dynamics Distort Land Law Reform in Mozambique?

Akiyo AMINAKA

Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

July 2023

In many African countries, state power over land management does not always extend to every corner of its territory. Moreover, the state often acknowledges that customary laws govern rural common lands. This was the result of strategy of the ruling party in charge of running the state to garner political support in rural areas. How does the local political environment influence the implementation of land laws? My study of the case of Mozambique (Aminaka 2022) demonstrates that implementing land laws is heavily influenced by the political context.

Legal Design of Land Laws amid Global Interests

In many African countries, the new land laws in the 1990s were in response to global integration and international donors of development assistance. Both donors and recipient countries considered foreign direct investment as a catalyst for economic development. International donors of development assistance required recipient countries to implement land laws that clarify land rights.

The Mozambican government introduced a National Land Policy in 1995 and a new Land Law in 1997. Both were the results of discussions prompted by the acceptance of structural adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in the 1980s. These adjustment programs included deregulation, such as privatization of public enterprises and trade liberalization, to strengthen the role of the market, in exchange for additional financial support for countries with accumulated debt (Burr 2005; De Renzio and Hanlon 2007). The new land law aimed to establish private land-use rights while common lands remained under customary law. Customary law was adopted to protect the common lands and livelihoods of the communities residing in them (Tanner 2002). Customary law is overseen by traditional chiefs, who inherited their power from their family lineages. These chiefs had previously been used for indirect rule in rural areas during the colonial period. They were later removed from their authority by the socialist government (1977–89). However, with the customary law recognized, they regained their power to govern the common lands.

Since the early 2000s, foreign investment, particularly in natural resource development (e.g., mining, natural gas extraction, and agriculture), has surged. These investments directly affect land resource management in rural areas (Schut et al. 2010). This emphasizes implementing new land laws crucial for attracting investment while causing many land conflicts. To obtain land-use rights in rural areas ruled by the common laws, consulting the villagers and submitting agreement documents signed by 3–9 community representatives—including the traditional chief—is necessary. Policymakers believed that the rising disputes stem from the villagers’ lack of legal literacy. Hence, they planned to provide land law training to the locals and deploy assistants into rural areas (Tanner and Bicchieri 2014). However, legal literacy was not the root cause of the land conflicts. Rather, it was a political issue concerning the governance of rural areas.

Village Administration and Revival of Traditional Chief

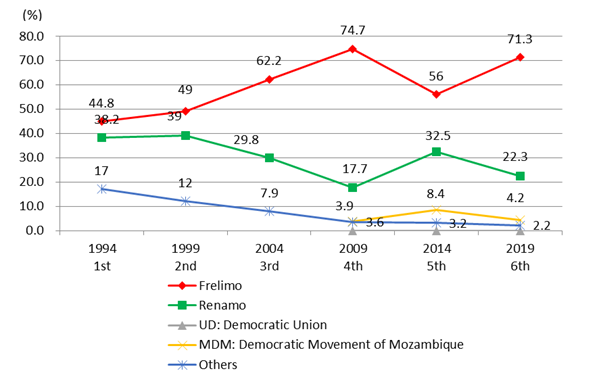

The first National Assembly elections (in 1994), close on the heels of multi-party system implementation, demonstrated a close competition between two political parties (Figure 1). The ruling party, Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), did not have a solid position. Moreover, FRELIMO sought to garner support in the rural areas where its rival, Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO), had a robust support. Consequently, FRELIMO resorted to distributing political and economic benefits to secure election victories, particularly in rural areas with significant support for RENAMO, leading to numerous land conflicts.

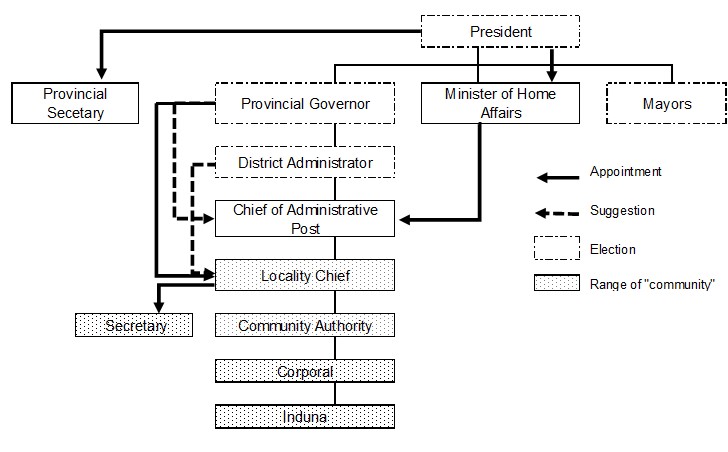

To strengthen its ties with the electorate in the villages, the FRELIMO administration devised a strategy to incorporate the villages into the administrative structure and establish a direct link with the central government (Figure 2). In so doing, the ruling party expected to strengthen their connections with village electorates. As part of this strategy, former traditional chiefs, who had lost their power during the socialist government era, were rebranded “community authorities” in 2000. Moreover, they were incorporated into the village administration. They now receive salaries and possess the authority to allocate financial resources for local development. This approach appeared effective for FRELIMO, and it may have resulted in it winning by the largest margin ever in the 2009 elections (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Turnout in the National Assembly Elections 1994–2019

Source: Created by the Author based on Aminaka (2022).

Figure 2. Structure of Administration and Routes of Appointment or Election

Source: Created by the Author based on Aminaka (2022).

Note: Traditional chief was renamed as community authority in 2000.

The Party-State’s Approach to Traditional Chief: Buy-In or Elimination

As the traditional chiefs were incorporated into the local administrative structure, their influence obtained political significance, affecting not only electoral events but also the implementation of laws at the local level. In my research, I compared the treatment of customary laws regarding land rights in two villages characterized by intense political rivalry between the two parties. Village A had a traditional chief supporting the ruling party (i.e., FRELIMO), while Village B’s chief was aligned with the opposing party. Both villages were in the Monapo district, where agricultural investment was rising. FRELIMO aimed to secure community approval for land rights transfer to investors, despite the numerous land conflicts in the area.

In Village A’s case, the ruling party politically reconciled with the traditional chief. Consultations about land rights were conducted privately rather than publicly. The traditional chief was expected to represent and safeguard the interests of the community members as per customary law. However, he failed to fulfill this role and made decisions contrary to the community’s interest, receiving favors from the ruling party in return.

In Village B, the traditional chief supported the opposition party. The district administrative office aligned with the ruling party. The administrative office organized an improper consultation process for land rights, intentionally excluding the traditional chief to eliminate any uncertainty about the chief opposing the issuance of new land-use rights.

Two crucial points became clear from these cases. First, regardless of whether the traditional chief supports the ruling or the opposing party, there is no inherent neutrality in the administration directly involved in the land resource management of the two villages. The absence of administrative neutrality is quite evident in today’s Mozambique. Second, regarding the management of rural land resources governed by customary law, the traditional chief does not necessarily act as the protector of common land and community members’ rights. In Village A, the traditional chief, a ruling party supporter, engaged in informal negotiations and relinquished their responsibilities to safeguard the community’s interests. In Village B, the traditional chief aligned with the opposition was excluded from the consultation and deprived of the opportunity to exercise their rights. In both cases, the expectation that rural land resources would be protected by incorporating customary law into the new land law has been betrayed.

Final Remarks

Mozambique’s new land laws were enacted in response to foreign donors’ demands and structural adjustment programs in the 1980s. However, the ruling FRELIMO government has utilized this to bolster its domestic rural support. Let us revisit the initial question.

How does the region’s specific political environment affect land law implementation? My research demonstrates the influence of political competition between two parties. The village administration does not escape the ruling party’s manipulation. The traditional chiefs failed to protect their communities against outside political and economic interests, often even favoring the outside interests when aligned with the ruling party.

Since the traditional chiefs have widely accepted legitimacy in society, the party–state’s manipulation of them for its own political interests engenders distrust and dissatisfaction against the government among the people. This may partially elucidate the sporadic conflicts that have recently emerged in various parts of the study area.

Author’s Note

This column is based on the following chapter (Open Access): Aminaka, Akiyo. 2022. “Politics of Land Resource Management in Mozambique.” In African Land Reform Under Economic Liberalisation, edited by Shinichi Takeuchi. Singapore: Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-4725-3_6

Reference

Burr, Kendall. 2005. “The Evolution of the International Law of Alienability: The 1997 Land Law of Mozambique as a Case Study.” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 43: 961–97.

De Renzio, Paolo, and Joseph Hanlon. 2007. “Contested Sovereignty in Mozambique: The Dilemmas of Aid Dependence. Managing Aid Dependency Project.” GEG Working Paper no. 2007/25. Oxford: University College Oxford.

Schut, Marc, Maja Slingerl, and Anna Locke. 2010. “Biofuel Developments in Mozambique: Update and Analysis of Policy, Potential and Reality.” Energy Policy 38 (9): 5151–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.048.

Tanner, Christopher. 2002. “Law-Making in an African Context: the 1997 Mozambican Land Law.” FAO Legal Papers Online no. 26. www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/legal/docs/lpo26.pdf. Accessed 21 April 2021.

Tanner, Christopher, and Marianna Bicchieri. 2014. “When the Law Is Not Enough: Paralegals and Natural Resources Governance in Mozambique.” FAO Legislative Study no. 110. www.fao.org/3/i3694e/i3694e.pdf.

* Thumbnail photo: Landscape of Monapo District, Nampula Province, Northern Mozambique. Author’s photo, August 2016.

** The views expressed in the columns are those of the author and do not represent the views of IDE or the institutions with which the author is affiliated.